A Gallery of People Around John Bunyan

“Mary” Bunyan

Upon release from his tour of duty as a soldier in the Parliamentary ranks, John Bunyan married his first wife. Her name is speculated to be “Mary:” as it was customary to name one’s first daughter after the mother, and this was the name of the Bunyan’s blind daughter.

Although Mary was monetarily poor, her dowry was of priceless value to John’s future. Mary brought a practical faith to her marriage, as well as stories of her Godly father. Bunyan writes, “She would be often telling me of what a Godly man her Father was, and how he would reprove and correct Vice, both in his house, and amongst his neighbours; what a strict and holy life he lived in his day, both in word and deed.”

The Bunyans were so poor that John once wrote that they did not have “so much household stuff as a dish or a spoon betwixt us both.” But Mary did bring two books that would influence John’s life and ministry. The books were, The Plaine Man’s Path—way to Heaven, Wherein every man may clearly see, whether he shall be saved or damned, written by Arthur Dent; and Lewis Bayly’s book, The Practice of Pietie, directing a Christian how to walke that he may please God.

Their two daughters, Mary and Elizabeth, were born in Elstow, where they were baptized before the family moved to Bedford in 1654 to be closer to Gifford’s Church. This is significant because it was the Anglican, or State, Church that upheld infant baptism. This meant that although John joined the Bedford Congregation, Mary seems to have stayed loyal to the state church.

At the time of her death in 1658, Mrs. Bunyan left her husband with two daughters and two sons—Mary, Elizabeth, John, and Thomas.

Elizabeth Bunyan (c. 1641–1692)

After the death of his first wife, Bunyan married Elizabeth in 1659. Elizabeth, around the age of 17 or 18, was much younger than the 31—year—old father of four children, John Bunyan.

Her groom was imprisoned shortly after their marriage, yet her loyalty and love for her husband shone brightly as she went before the judges of Bedford to plead Bunyan’s case in August of 1661. Earlier Elizabeth travelled to London to present a petition to the Earl of Bedford requesting her husband’s release, probably her first trip to London. But the petition was denied. In August she went before Judges Hale and Twysden who sat in the Swan Inn in Bedford in the Swan Chamber. Justice Chester and many other members of the local gentry were present to witness the bravery and tenacity of this young bride.

Yet Bunyan remained imprisoned for unlicensed preaching. Even though his time in prison could have been as short as three months if he would relinquish his desire to preach the gospel, to Bunyan it was not only his responsibility to preach but his right and privilege as well. Thus, he moved his ministry to the prison—Elizabeth and the children would visit him, while he continued to write, counsel, and preach.

Elizabeth continued to encourage her husband in his ministry even after the miscarriage of their first child due to the stress and strain of his imprisonment.

During the year of 1666, Elizabeth and John’s daughter Sarah was conceived. Soon after Bunyan was released in 1672 under the “Quaker pardon,” Elizabeth gave birth to their son, Joseph.

In 1676 and 1677, Elizabeth and John were separated by his second imprisonment. On August 31, 1688, John Bunyan died of a severe cold due to overexposure. And in 1692 Elizabeth died, but only after releasing more of her husband’s writings to be published.

“Blind Mary” Bunyan (1650–1663)

Mary, the eldest of John Bunyan’s six children from his two marriages, was born in July, 1650. Her joyful parents asked Christopher Hall, the Vicar of Elstow Church, to christen the child. Not long after, however, their hearts were filled with sorrow when they learned that Mary was born blind. She became known as “Blind Mary:”

The deep relationship between Bunyan and his first daughter is clearly seen in his writings about her. While in prison, he was allowed limited visitation privileges with friends and family, and Mary knew the way by heart. As months of imprisionment turned into years, his daughter would faithfully bring Bunyan soup for his supper, carried from home in a little jug.

Bunyan explains in Grace Abounding that these visits were bittersweet for both his daughter and himself. “The parting with my wife and poor children hath oft been to me in [prison] as the pulling the flesh from my bones . . . especially my poor blind child, who lay nearer my heart than all I had besides; O the thoughts of the hardships I thought my blind one might go under, would break my heart to pieces. Poor child, thought I, what sorrow must thou have for thy portion in this world? Thou must Blind Mary’s soup jug be beaten, must beg, suffer hunger, cold, nakedness, and a thousand calamities, though I cannot now endure the wind should blow upon thee.”

In the spring of 1663 Mary fell sick, and died soon after. She was the only one of the Bunyan children that did not outlive their father. From the news of her passing within the confines of his cell, Bunyan began the outline of The Resurrection from The Dead—a book of inspiration for many years to come.

John Gifford

John Gifford was a changed man in 1650. He was changed from the Major in the Royalist Army who surrendered to General Fairfax of the Parliamentary forces. He was changed from the repulsive man of bad habits—the gambler, drunkard, and blasphemer. In that year Gifford was changed into the man that John Bunyan refers to as “Holy Mr. Gifford.”

His life began to change as he read Mr. Bolton’s Last and Learned Works of the Four Last Things—Death, Judgment, Hell and Heaven. The simple truths held within became clear to Gifford, particularly that he was a sinner and that God’s grace through Jesus Christ was sufficient for all his sin.

Within a month’s time his life was transformed, and the Bedford physician became the pastor of the newly formed congregation of Nonconformists.

It was this same man who had just made his own spiritual pilgrimage that spoke to John Bunyan in the rectory of St. John’s. They talked about salvation and the true message of Jesus Christ.

Yet John Bunyan continued to battle this spiritual war for another year after his conversation with Mr. Gifford. It was at this period in Bunyan’s life that he came across Martin Luther’s Commentary of the Epistle of St. Paul to the Galatians. It became his most valued book, with the exception of the Holy Bible. Bunyan was under Gifford’s ministry from 1651, but it was not until 1653 that he became part of the Bedford Congregation.

John Gifford remained the pastor in Bedford for five years until his death in 1655. He was mourned by many members of the town and surrounding communities. The “Holy Mr. Gifford” was buried in the churchyard of St. John’s.

John Owen (1616–1683)

Bunyan’s preaching and writings found ready acceptance among England’s poorer classes, but appreciation for his work was not limited to those of humble condition. Among the educated and prominent men with whom Bunyan shared ideas and pulpits was Dr. John Owen.

The son of a Puritan Minister in Stadhampton near Oxford, Owen graduated from Queen’s College, Oxford, at 16 years of age, and was ordained a few years later. He served as chaplain to two Puritan families, then was appointed by Parliament to the Fordham parish in Essex. Owen became increasingly Congregational in his views on church government, expounding Congregational principles in his writings, and modelling them in his church. He worked closely with Oliver Cromwell, and served as his chaplain in 1650. The next year Owen was appointed Dean of Christ Church, Oxford. From 1652 to 1657 he served as Vice—Chancellor of Oxford University.

With the restoration of the monarchy in 1660, Owen was dismissed from Christ Church. He turned down an invitation to pastor First Church of Boston, Massachusetts. Moving to London, Owen lead a non-conformist congregation and continued his writing. Owen’s London congregation, where Bunyan sometimes preached, included such well-known people as General Charles Fleetwood, Cromwell’s son-in- law; Sir John Hartop; Sir Thomas Overbury; and the Countess of Anglesey.

John Owen’s works are still in print today (in 16 volumes by the Banner of Truth Trust, and in other editions), and he has been called perhaps the greatest of all English theologians.

It is recorded that King Charles II once asked John Owen how such an educated man as he could sit and listen to the illiterate tinker Bunyan, to which Owen replied, “May it please your majesty, could I possess that tinker’s abilities for preaching, l would most gladly relinquish all my learning.”

William Kiffin (1616–1701)

Kiffin was one of the most esteemed among the first generation of English Baptists in the seventeenth century. He was a “particular” or Calvinist Baptist, as was Bunyan, but was disturbed that Bunyan had become too liberal on the issue of Baptism itself. Kiffin was one of the wealthiest of the earliest Baptists from his income earned in the woolen trade. He loaned King Charles II the sum of 10,000 pounds thereby securing some influence for his Baptist interests. He organized the first Particular Baptist Church at Devonshire Square and served as pastor there for over 60 years. He was one of the signers of the classic Baptist document: The First London Confession.

Kiffin struggled to keep Bunyan within the strict interpretation of baptism held by the “Particular” Baptists. Their divergence is set forth in Bunyan’s work which is a mediating position Differences in Judgment About Water Baptism, No Bar to Communion. Bunyan refused to exclude any Christians from either church membership or the Lord’s supper because of how or when they were baptized. Bunyan’s church ended up affiliating with both the Baptists and the Congregationalists.

Oliver Cromwell (1599–1658)

Under Cromwell’s leadership, Puritanism and separatist groups became firmly established in England. It was during these years that Bunyan experienced a conversion, was baptized by John Gifford, and began to preach publicly.

Cambridge educated, Oliver Cromwell was first elected to Parliament from his home town of Huntingdon in 1628. His political and military leadership brought him to the fore during the English Civil War, and he served as general of the victorious Parliamentary army. After the war, when it became clear that Parliament was unable to rule and the only effective authority rested in the army, Cromwell acquired greater control and was installed as Lord Protector of the Commonwealth, essentially a military dictatorship (1653–1658).

Cromwell had been a champion of religious liberty during his years in Parliament, arguing for the rights of the non-conformists who were being silenced by Charles I. Cromwell himself was a committed Puritan, and the troops of his army carried Bibles, prayed, and sang psalms. During the Protectorate, Cromwell achieved a great degree of religious toleration, attempting to organize the church so that all true believers could worship according to conscience.

Through Cromwell’s direct influence and flexible ecclesiastical policies came the appointment of John Gifford as parish minister at St. John’s, the same “Holy Mr. Gifford” that profoundly shaped John Bunyan’s ministry. When Gifford died in 1655, Cromwell’s own nominee became rector of St. John’s and minister of the Independent congregation, the man was John Burton. (Sixteen years hence the congregation would choose John Bunyan to pastor the Bedford church. )

On his deathbed in 1658, Cromwell made a belated decision to appoint his son Richard as Protector. A lackluster leader, Richard abdicated the next year.

King Charles II (1630–1685)

It was during the reign of King Charles II that Bunyan suffered long years of imprisonment for his faith.

In 1660 Charles II returned from exile in France and Holland to take the throne, restoring the English monarchy. In the Declaration of Breda (1660), Charles promised that “none of you shall suffer for your opinions or religious beliefs so long as you live peaceably.” His concern for liberty of conscience, however, was not shared by the less tolerant Parliament and the restored Anglican bishops and clergymen. Before long, conformity to the Anglican church was a matter of law, and a series of acts oppressing religious dissent was enacted.

Charles II was crowned on April 23, 1661. His coronation was accompanied by a general release of prisoners who were awaiting trial and by a postponing of sentences while convicted prisoners sued for pardon. Bunyan was already imprisoned at this time. Charles’s coronation brought hope of a release which, because of a technicality, never came to fruition.

In 1672 Charles signed the Declaration of Indulgence, suspending the laws which had oppressed Catholics and Nonconformists. It was under this that Bunyan was finally able to petition successfully for his freedom.

There is evidence that Charles was aware of Bunyan and his work. He is quoted as asking John Owen about Bunyan’s preaching. In later years, the King owned copies of some parodies of Bunyan’s writings.

Judge Sir Matthew Hale

Sir Matthew Hale first appeared to the public eye as a member of Parliament under Oliver Cromwell. After the Restoration of the monarchy Hale was made Chief Baron of the Exchequer. In 1671 he became Lord Chief Justice. In addition, Hale authored History of the Common Law of England and other legal works.

Having been educated among Dissidents, Hale was reputed to be sympathetic toward them and to try to mediate the harshness of the law in their favor. This reputation led Elizabeth Bunyan to approach the judge in 1661 in several attempts to free John. Hale was one of the judges who eventually heard her formal plea at the Assizes in Bedford.

By all accounts a kindly man, Judge Hale seemed inclined to favor Elizabeth’s request and to be deeply touched by her story. The other judges sitting with him on the case convinced him to rule that Bunyan had been fairly convicted.

Hale did give Elizabeth further legal advice, suggesting that she should apply directly to the King, “sue out” a pardon, or obtain a writ of error, which would imply that injustice had been done.

Paul Cobb

Paul Cobb was a clerk of the peace during the time of Bunyan’s imprisonment.

Bunyan had been convicted under the Statute 35 Elizabeth, which mandated that every citizen of the Commonwealth should attend the parish church regularly. The punishments for breaking this law included first, imprisonment, second, transportation, and, third, hanging.

Cobb was sent by the magistrates to visit Bunyan and plead that he submit himself again to the church and refrain from preaching. Apparently these issues were discussed many times, and Cobb seems to have become genuinely concerned for Bunyan.

Cobb tried to convince Bunyan to cease preaching temporarily, until the political climate improved. Bunyan refused and Cobb was forced to give him formal warning that he might be transported or worse after the next sessions.

Cobb later had Bunyan’s name removed from the “Kalendar” of cases to be tried in what may have been an effort to save Bunyan from himself.

Bunyan always felt that Cobb had been used of the enemy to lengthen his imprisonment.

Justice Twysden (also Twisden)

Justice Twysden sat with Justices Hale and Chester when Elizabeth Bunyan made her plea at the Assizes in Bedford.

Twysden was quite prejudiced against the case. This was partially from his natural aversion to Dissidents and partially because of an unfortunate incident in 1661.

When Elizabeth travelled to London to try to obtain a pardon for her husband, she went first to Justice Hale. After being turned away by him, in desperation she stopped Tywsden’s coach and quite literally threw her petition in his lap. He was so angered by this that he told her Bunyan would never be set free unless he would stop preaching.

When Elizabeth pled her case before him in Bedford, Twysden went into an angry tirade, claiming that John did the Devil’s work. Twysden effectively resisted any softening toward the Bunyans asked by Justice Hale.

By the Editors

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #11 in 1986]

Next articles

Christian History Timeline: John Bunyan and Pilgrim’s Progress

Chronology of events associated with John Bunyan.

the EditorsPrincipalities and Powers: Authorities in Conflict

The events of Bunyans life were played out in 17th century England. It was a time when politics and religion were inextricably intertwined, and both state and church were facing major conflicts.

the EditorsThe Pilgrim’s Progress: A Dream That Endures

Furnishing as it did much counsel, caution and consolation amid the toilsome traffic of daily life, Pilgrim’s Progress bore a message that was at once both useful and agreeable.

James F. ForrestWhat Shall I Do to Be Saved?

The opening scene of The Pilgrim’s Progress presents a solitary figure crying out in anguish. His distress expresses Bunyan’s own tormenting struggle with sin—yet not his alone. Throughout the book’s history, readers have seen themselves in the man with the great burden on his back, and recognized their own spiritual pilgrimages in Christian’s journey to the Celestial City.

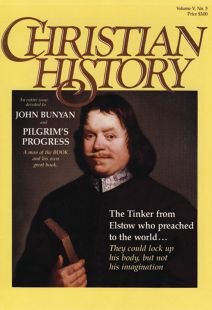

John Bunyan