“Go forth to every part of the world”

ON MARCH 19, 1946, leading US newspapers published an image of five members of Youth for Christ (YFC) kneeling in prayer in front of an American Airlines plane. Among the five young men in the picture was 27-year-old Billy Graham. The plane took the young evangelist on his first missionary trip to Europe. It was the first ever commercial flight from Chicago to London, and the Youth for Christ team took advantage of the publicity surrounding this historic event.

Together with fellow evangelists Chuck Templeton, YFC president Torrey Johnson, and song leader Stratton Shufelt, Graham set out on a 46-day tour to Britain and Europe. Graham returned in fall of the same year for another six months. Then in 1948 he went back to Europe for more YFC rallies and to attend YFC’s Congress on World Evangelization in Beatenberg, Switzerland.

That meeting exposed him to some 250 other delegates attracted by the theme “The Evangelization of the World in Our Generation.” Even though the YFC movement was still predominantly American, delegates came from 46 nations—from as far away as China, Egypt, India, and the Philippines. These young missionaries realized that the new global reach of communication, broadcasting, and air travel would alter the very nature of missionary work in the second half of the twentieth century. Thus, through his early work with Youth for Christ, Graham became part of a new, young international community of evangelists.

These European travels took place during the three years before Graham came to national prominence during his 1949 Los Angeles campaign. These early experiences abroad significantly shaped Billy Graham. As his biographer William Martin wrote, meetings with influential religious individuals, such as the young Welsh evangelist Stephen Olford, had a significant impact on Graham’s faith and his preaching style.

Seeing the hopelessness and despair of postwar Europe also made a strong impact on the young preacher. Graham saw destruction, hunger, and many people who had lost their faith during the hardship of the war years. His revivalist theology, his machine-gun-like preaching, and his loud neckties all drew opposition from British church officials. In Birmingham, England, the local clergy even persuaded the city fathers to revoke permission to use the civic auditorium. Graham responded to their opposition by personally meeting with his critics and winning them over. All these experiences seem to have strengthened Graham’s faith, and his preaching became more intense. During this time, he decided to dedicate an important part of his career to re-Christianizing Europe.

A life commitment

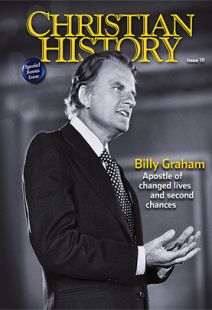

Graham’s dedication to the re-Christianization of Europe became a lifelong commitment. Even after his rise to national fame in the United States, he dedicated a significant amount of his missionary time to Europe. In spring 1954 he held his first three-month revival meeting in London, then the largest city on Earth. The crusade confronted Graham’s team with significant logistical challenges, but at the same time prepared them for future campaigns in other metropolises such as New York and Berlin.

After his successful time in London, with a closing service held at Wembley Stadium which attracted 120,000, he traveled to the Netherlands, Germany, Scandinavia, and France. His first revival service at the Olympic Stadium in Berlin in June 1954 attracted an audience of 80,000 and laid the groundwork for a close and lasting relationship between Billy Graham and German Christians. He would return to the country for campaigns—some shorter, some longer—in 1955, 1960, 1963, 1966, 1970, 1982, 1990, and 1993.

By 1954 the European religious, political, and economic landscape had changed significantly since Graham’s first trip to the British Isles only one year after the end of World War II. In particular, Germany and the United Kingdom had formed a close relationship with the United States. Graham’s strong anticommunism resonated particularly well with audiences in West Germany, and Germans embraced the evangelist as an ambassador of the Free World. For European consumers Graham’s image as a healthy, middle-class American became an attractive symbol of the American way of life. But Graham also profited from new support through the established churches. Secularization fears and re-Christianization hopes made leading European religious figures take their seats next to Graham on the speaker’s platform during his revivals. Archbishop of Canterbury Geoffrey Fisher joined him in London, while Bishop Otto Dibelius of Berlin-Brandenburg offered the closing prayer at Berlin’s Olympic Stadium.

By the mid-1950s, Billy Graham had traveled Europe and Asia to spread the gospel, and his international outreach began to shape his domestic crusades. The New York Crusade, which opened at Madison Square Garden on May 15, 1957, incorporated and displayed the international dimension of Graham’s work. Even though Madison Square Garden was decorated in American colors, with American flags hanging from the ceiling, the crusade was important not just to American Christians. By April 1957 around 7,000 prayer groups had formed worldwide. Many of these were based in cities where Graham had preached before.

Letters published in the New York Crusade newsletter reported that people in London, Basel, Mexico City, Havana, Hong Kong, and Tokyo were praying for the crusade. In Britain alone over 1,000 prayer partners gathered in groups. Through prayer the crusade audiences that gathered at different times and on different sides of the globe blended into one global evangelical community. As the Reverend Joseph Blinco, a British evangelist who joined Graham during the New York Crusade, observed: “The shortest route to New York from any point of the world is not by the magnificent air lines that serve this fantastic age, but through the heart of God on the wings of prayer.”

Blinco was not the only “foreigner” who joined Graham in New York. Other British Christians who had experienced Graham’s work in England in 1954 and 1955 flew to New York to participate in the crusade. Irene Hicks, for example, worked for Harrods in London and had accepted Christ during the London Crusade. She happened to be on a business trip to New York and gave a public testimony at the New York Crusade.

It became obvious that Graham’s team was willing to learn from their British brothers and sisters when they used an outreach tool known as “Operation Andrew.” Operation Andrew (OA) involved churches chartering buses to take their members and, more importantly, friends of their members to the crusades. OA was the brainchild of British evangelicals who organized the London Crusade in 1954 where it was born of necessity. In New York Graham’s team adapted to the American context and used it to connect suburbs with the urban center. In the New York Crusade News of May 1957, Walter H. Smyth, director of the crusade’s group reservations department, encouraged churches to use Operation Andrew. “The effectiveness of this plan as a soul-winning effort cannot be over-emphasized,” he wrote.

A global vision

The boundaries between Graham’s national and international work eventually blurred, and he became the face and focus of an increasingly international evangelical community. The international evangelical meetings Graham took part in expanded the global reach of his organization. They also created a new international evangelical network.

In 1966 Graham gave the keynote address at the World Congress on Evangelism, which was organized by Christianity Today and the Billy Graham Evangelistic Association and was held in Berlin after yet another successful Graham campaign in England and Germany. The congress attracted a significantly larger and more international community than the one that had met at Beatenberg 20 years earlier. Around 4,000 Christian leaders from 100 different countries went to Berlin including Haile Selassie, the emperor of Ethiopia.

In his speech “Why the Berlin Congress?,” Graham revealed not just his global vision for evangelism, but showed also a detailed knowledge of the global challenges of that decade when he addressed overpopulation, poverty, and racial struggles. Billy Graham had seen these problems firsthand during his many trips abroad, and he had the authority to discuss them at the congress. It became clear in his speech just how much his own global encounters had changed Graham. The evangelist, often criticized for his focus on personal conversion rather than social activism, said, “Today, the evangelist cannot ignore the diseased, the poor, the discriminated against, and those who have lost their freedom through tyranny. These social evils cry loudly in our ears, and we, too, must ‘have compassion on them.’ ” How to balance evangelism and social responsibility was much debated in evangelical circles in the 1960s and 1970s.

The question also featured prominently in the discussions eight years later, when 2,700 delegates from 150 countries answered Billy Graham’s invitation to the 1974 Lausanne Congress on World Evangelization. The meeting gave birth to the Lausanne Movement, an umbrella organization of evangelical Christians worldwide. The diversity of these delegates proved that the world had become smaller. Dynamic new evangelical players joined from Asia, Africa, and Latin America. The Lausanne Congress highlighted evangelicalism’s new global identity and also displayed the significantly increased global knowledge in evangelical missionary circles. When delegates discussed the concept of “unreached people” as the focus of future missionary work, they did so now based on expert knowledge, maps, and data. Evangelical missionaries had traveled the globe for centuries, but they now developed a more analytical understanding of the challenges ahead. This became concrete when the Lausanne steering committee commissioned a report on the state of Christianity in every country of the world.

The global community present at Lausanne was the fruit of seeds planted by YFC’s international campaigns and the crusades that Graham had held on all five continents in the 1950s and 1960s. They were closely knit by air travel, the rise of international media, and ever faster communication technology. They were nourished by the shared memory and experience of Billy Graham’s international campaign work, while growing closer through the global practice of prayer.

Graham eventually preached evangelistic messages in 49 countries. His international outreach is often underestimated in the United States, and many US evangelicals don’t understand the ways his global ministry both transformed him as an evangelist and shaped his work in his home country. CH

By Uta Balbier

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #111 in 2014]

Uta Balbier is director of the Institute of North American Studies at King’s College London. Her research focuses on US and transnational religious history.Next articles

Watershed: Los Angeles 1949

The revival that took Billy Graham from anonymity to national fame

Grant WackerBilly Graham, Did you know?

Billy Graham’s political temptation, his friendships with entertainers and heads of state, and the impact of his music team

the editors“I would not call it show business”

Media made Billy Graham a celebrity; Graham worked hard to stay honest and authentic

Elesha Coffman