Healing the city

IF YOU HAD THE MISFORTUNE of becoming sick in classical Greece or Rome, it was your problem.

Responsibility for health was regarded as a private, not a public, concern. In spite of the damage wrought in the ancient world by several well-known epidemics, virtually all victims of infectious disease were left to deal with their symptoms themselves. Public officials did not believe they had any responsibility to prevent disease or to treat those who suffered from it.

Philanthropy among the Greeks did not take the form of private charity, nor was it driven by a personal concern for those in need. There was no religious or ethical impulse for almsgiving: philanthropic acts were undertaken for the purpose of increasing one’s personal reputation.

The classical world did not recognize emotion or pity as a desirable response to suffering or as a motive for personal charity. And when donors did make gifts or perform services, they intended them for the entire community. Any benefaction (civic gift), endowment, or foundation had to be provided for all members of the city-state, rich and poor alike; this was true all the way from Greek city-states in the fifth century BC up to large thriving cities of the Roman Empire in late antiquity, over 700 years later.

The sick poor simply did not have an identity as a defined group that deserved special consideration. Classical society required a new movement, arising outside the traditional framework of the classical world, to challenge this assumption. That movement was Christianity.

Widows and orphans

From the beginning Christian charity stood in stark contrast to that of the Greeks and Romans. The church displayed a marked philanthropic imperative, showing both personal and corporate concern for those in physical need (as in Acts 6:1–6).

Christians regarded charity as motivated by agape, a self-giving love of one’s fellow human beings that reflects the redemptive love of God in Jesus Christ. Ordinary Christians were encouraged to visit the sick and aid the poor as an individual duty. But the early church also established organized assistance.

Each church had priests and deacons who directed the corporate ministry of the congregation. Deacons, whose main concern was the relief of physical want and suffering, had a special responsibility to visit the ill and report on their condition to priests.

Churches received collections of alms every Sunday for those who were sick or in want, which were administered by priests and distributed by deacons. Widows who did not need assistance formed a separate class that later developed into the office of deaconess. They were expected to help the poor, especially women, who were sick.

So, although their numbers and resources were often small, Christians were equipped, even in the most adverse of circumstances, to undertake considerable charitable activity on behalf of those who were ill. Owing to a combination of inner motivation, self-discipline, and effective leadership, the local Christian church created in the first two centuries of its existence a system that effectively and systematically cared for its sick.

Priests, deacons, and doorkeepers

In the third century, the rapid growth of the church, particularly in the large cities of the Roman Empire, led to the organization of benevolent work on a larger scale. Roman cities were crowded, often unsanitary, and for many lonely. Large numbers of city-dwellers had no family or support network because they had migrated from rural areas hoping to find jobs (see “Did you know?,” inside front cover).

As the number of those who benefited from the church’s charitable activity increased, there were too few deacons and priests to deal with the demands made on them. Congregations began to create minor clerical orders to assist them.

We can thank church historian Eusebius for preserving a letter written in 251 by Cornelius, bishop of Rome, to Fabius, bishop of Antioch. In it we learn the specifics of Rome’s extensive efforts. They supported 46 priests, 7 deacons, 7 subdeacons, and 42 acolytes, as well as 52 exorcists, readers, and doorkeepers—a staff of considerable size!

Apparently the church in Rome had divided the city into seven districts, each under a deacon, who was assisted by a subdeacon and six acolytes. They cared for 1,500 widows and distressed persons who were supported by the church; the Roman church may have spent each year from 500,000 to one million sesterces on the maintenance of those in need. (A sesterce would buy you approximately two loaves of bread, and 500 of them would buy you a donkey; the denarius often mentioned in the Bible as a day’s wage was worth four sesterces.)

And Rome was not alone. John Chrysostom wrote a century after Cornelius‘s letter that the Great Church in Antioch supported 3,000 widows and unmarried women along with other sick and poor people and travelers.

All this—the establishment of minor orders to assist priests and deacons, the creation of sizable staffs of clergy in large churches, the churches’ regular support of considerable numbers of the poor and sick, and the expenditure of large sums of money—suggests that churches devoted a good deal of attention to corporate philanthropic activity.

Before the legalization of Christianity in AD 313, ongoing care for the sick was viewed as only one part of the church’s charitable ministry. Much care was directed toward relieving individual suffering rather than to therapeutic treatment to make the patient better. In many cases the care was rudimentary: Christian care of the sick relied primarily on the clerical orders, composed of men chosen for their spiritual rather than medical qualifications.

The zealous ones

Two nonclerical groups founded in the late eastern Roman Empire that administered medical assistance in the urban churches were the lay orders of spoudaioi (“the zealous ones”) and, in Egypt, the philoponoi (“lovers of labor”). These men and women were attached to large churches in the great cities of the east: Alexandria, Antioch, Constantinople, Beirut, and Jerusalem, most prominently, although they are attested in other smaller cities as well. A chief function of both groups was to provide assistance to the homeless sick of the urban areas in which they lived.

Greek writings refer to indigent sick who thronged the streets of Greek cities. Uncared for in public places, they were without resources, and either had no one to care for them or had family and friends who had set them out to die. There existed no provision for public or private shelter or care of any kind for the destitute. Hence they were often forced to live on the streets, or in porches, tombs, or makeshift dwellings.

Public baths provided fresh water essential for hygiene and furnished some warmth in cold winters. Some of the sick of all classes sought the assistance of Asclepius, the Greco-Roman god of healing, in his temples. But those afflicted with mental disorders or loathsome diseases were often driven away, as is recorded in several instances in the Gospels.

Even in time of plague, municipalities made no provision for burying the dead, who were often thrown into the streets. It was to these urban poor, sick or dying on the streets, that the spoudaioi devoted their service. They would frequently search the streets and alleys at night for those who were ill, distribute money to them, and take them to public baths.

This overall perception that the church had an obligation to care for the sick poor was basic to the founding of the earliest hospitals (see CH issue 101). The hospital was, in origin and conception, a distinctively Christian institution.

There were no pre-Christian institutions in the ancient world that served the purpose that hospitals were created to serve, namely, the offering of charitable aid, particularly health care, to those in need. Roman infirmaries, called valetudinaria, were maintained by Roman legions and by slaveholders, but they provided medical care to a restricted population of soldiers or slaves, and they were not charitable foundations.

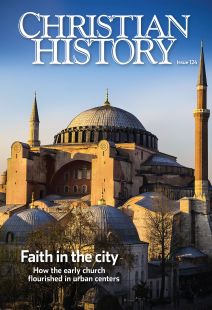

Order Christian History #124: Faith in the City in print.

Order Christian History #124: Faith in the City in print.

Subscribe now to get future print issues in your mailbox (donation requested but not required).

The earliest hospitals, called nosokomeia or xenodochia, grew out of the long tradition of care for the sick by deacons in Christian churches. The best known, and the earliest, was the Basileiad, begun about 369 and completed about 372 by Basil the Great, who became bishop of Caesarea in Cappadocia (see “A bishop’s work is never done,” pp. 12–15).

General hospital

Basil’s hospital employed a regular live-in staff that provided not only aid to the sick, but also medical care in the tradition of Greek medicine. It included a separate section for each of six groups: the poor, the homeless and strangers, orphans and foundlings, lepers, the aged and infirm, and the sick.

Hospitals spread rapidly in the eastern Roman Empire in the fourth and fifth centuries, with bishops taking the initiative in founding them. They appeared in the western empire a generation after they were established in the east, but their growth was much slower owing to economic difficulties in the west.

Only a minority of hospitals had the resources to employ physicians, and those that did were situated in the Byzantine east. In western Europe there were few physicians in hospitals until the end of the Middle Ages in the fifteenth century.

Hospitals were founded specifically to provide care for the poor (Basil called his hospital a ptochotropheion, or poorhouse). This pattern of hospitals caring for the poor would persist until the mid-nineteenth century, and for centuries hospitals remained institutions for the indigent. In some cases these unfortunates were taken off the streets and given a place in which to die. Those who could afford a physician’s care received it in their homes.

As late as the fourth century, despite Christians’ activities, the concept of being a “lover of the poor” (philoptôchos) was still a novel one in the Greco-Roman world. The community was still viewed as a collective whole, one in which all citizens of the city, rich or poor, shared in public benefactions. Therefore, a specific group defined as “the poor” (hoi ptochio) was still not singled out as recipients of charity.

Many wealthy pagans continued to espouse the traditional classical view that the poor were passive targets of malevolent fates, and they looked down on them as base and ignoble in

character. Christians—influenced by biblical texts that speak of the care of the poor as a duty—saw the poor instead as especially blessed by God, endued with grace, and even in their poverty bearing the image of God.

The faithful regarded philanthropy as demonstrating love for Christ. Both donor and recipient came to regard themselves as fellow servants, a theme that one finds in sermons of Christian clergy in the fourth and fifth centuries.

After the legalization of Christianity, distinctive Christian ideas of charity finally enjoyed public recognition by the government. The lower classes of the city came over time to replace all citizens as the main beneficiaries of assistance.

This little-noticed movement—the belief that the sick poor were everyone’s problem—marked one of the truly revolutionary changes in human sentiment in Western history and constituted a significant feature of the transition from a classical to a Christian society. CH

This article is from Christian History magazine #124 Faith in the City. Read it in context here!

By Gary B. Ferngren

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #124 in 2017]

Gary B. Ferngren is professor of history at Oregon State University and professor of the history of medicine in the I. M. Sechenov First Moscow State Medical University. He is the author of Medicine and Health Care in Early Christianity and other books on the history of medicine and faith. This article is excerpted from selected portions of Medicine and Religion: A Historical Introduction by Gary B. Ferngren (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2014) and is reprinted by the permission of the publisher.Next articles

“The only stumbling block is the cross”

We spoke to Doug Banister, the pastor of All Souls Church in Knoxville, Tennessee, about how his church does urban ministry.

Doug Banister and the editorsChristian History timeline: the tumultuous life of early urban Christianity

The Christian History timeline for the early church in Roman cities

the editorsThe things that are Caesar’s

How Christians behaved as citizens, soldiers, and public servants

Rex D. Butler“The same kind of Christians we have always been”

We spoke to Karen Swallow Prior, author of Booked (2012) and Fierce Convictions (2014) and professor of English at Liberty University, about how Christians ought to live as citizens in the culture.

Karen Swallow Prior and the editors