“Heaven at last the wrong shall right”

IN 1843 SING SING’S RESIDENT CHAPLAIN, John Luckey (1800–1876), went to New York’s head prison inspector, the lawyer and judge John Edmonds (1799–1874), to plead the case of a suicidal inmate. According to Luckey’s memoir, Life in Sing Sing State Prison, as Seen in a Twelve Years’ Chaplaincy (1860), the inmate deliberately tried to provoke a fatal beating, seeking immediate death over the slow one of serving out his sentence.

To the chaplain’s surprise, Edmonds appeared moved, visited the inmate, and stopped the keepers from lashing him. The prisoner became a hard worker in the prison shop. Edmonds then pressed Sing Sing’s prison agent Elam Lynds (1784–1855) to modify his notoriously severe discipline focused on order and profit. When Lynds refused Edmonds called for his removal. In 1844 New York officials relieved Lynds of duty.

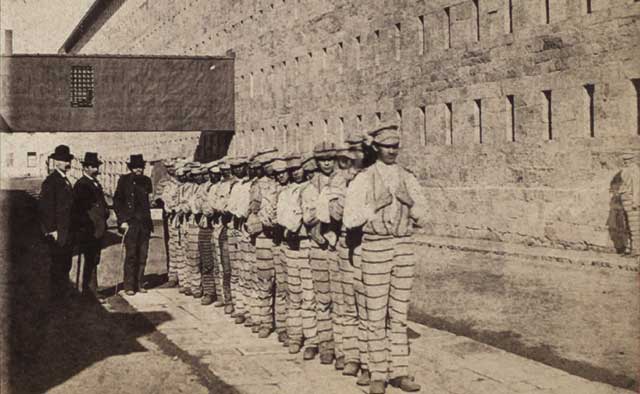

[Sing Sing-Prisoners going to work—Wikimedia: New York Public LIbrary, Stephen A. Schwarzman Building / Photography Collection, Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs]

The victory, however, was short-lived. In fact Luckey’s enlistment of Edmonds led to a new series of conflicts as Edmonds founded the New York Prison Association (NYPA). The NYPA wanted less severe prison discipline and inmate reformation, just like Luckey. But its main focus was on fostering a civil society, not on spiritual transformation. Only a few years later, Edmonds would help orchestrate Luckey’s dismissal from Sing Sing.

Unable to use a knife and fork

With the backing of Governor William Seward, Luckey had come to Sing Sing in May 1839. He could not have appeared at a more dramatic moment; Seward was investigating cruel warden Robert Wiltse. While he only served under Wiltse a few months, Luckey’s ministry was dominated by the aftermath. For example Luckey dealt with one Irish prisoner, a “used up man,” who had been “absolutely brutalized” by near-weekly floggings. He had forgotten how to use a knife and fork when he was pardoned after 20 years and could not stop himself from prison-lockstepping

down New York City sidewalks.

Luckey relished the opportunity to be part of Sing Sing’s fresh start under new agent David Seymour, who replaced Wiltse. He appreciated Seymour’s commitment to Sabbath school and the prison library, and was soon visiting inmate families, bringing in temperance speakers, and assisting inmates in transitioning to post-prison life. But most of all, he relished the “mildness” of the new discipline. Keepers used the lash infrequently. Mentally ill convicts received gentler treatment.

Luckey preached a message of suffering, conversion, and regeneration, emphasizing industriousness, morality, and self-discipline, and drawing on Methodist practices to shape his day-to-day ministry (see “William Morgan’s gift,” pp. 29–31). In fact Luckey functioned like a Methodist class leader inside Sing Sing. He visited prisoners regularly; listened to them to “advise, reprove, comfort, or exhort”; rebuked them; and tried to convince them of their need for prayer.

In Sunday chapel presentations, Luckey read letters from discharged convicts, assuring inmates that their affliction worked for good. Those discharged reported that they had read the Bible, learned new professions, and received the mercies of God. But all these things paled against the hope of heaven “through the merits of a crucified Saviour,” as one letter put it.

In 1840 the New York Evangelist attested to significant tract distribution and inmate conversion at Sing Sing. Articles detailed Luckey’s Sunday schedule—his sermon on the prodigal son, prayers with sick inmates, and afternoon visits to individual cells—and included inmate testimonies of thankfulness at having been brought to prison to learn the word of God.

Governor Seward’s reforms, however, lasted only as long as he remained in office. New Yorkers elected a Democratic governor in 1842 who named a new slate of prison inspectors, including Edmonds. Edmonds, in turn, hired Lynds. Lynds had previously served as warden at both Sing Sing and Auburn, where he founded the “Auburn system” of prison discipline. Lynds restored the tough discipline of his earlier terms. The number of floggings soared.

Lynds also ended the privileges of the last few years: family visitation, letters from friends, and singing in worship. He dismantled the prison library, stopped the Sabbath school, and curtailed Luckey’s interaction with prisoners. Despite increasing inmate population, budgets for food, clothing, and hospital supplies shrank. In an 1843 report, Edmonds and other inspectors wrote that “to talk of the power of moral suasion in a company of felons, is to talk nonsense.”

In his memoir Luckey referred to this period as a “bloody time” and a “reign of terror.” Mentally ill inmates suffered. On one occasion Luckey pleaded with Lynds not to flog one. Lynds responded that chaplains were “benevolent dupes.” But Luckey’s experience with the prisoner who tried to get himself killed by a fatal beating proved to be a catalyst for change. For starters it got Lynds fired.

Change for the better?

But the conflict was not over. Edmonds’s new NYPA rejected the belief that most prisoners were unredeemable, but its vision focused not on redemptive suffering but on prisoners’ potential for citizenship. Chaplains were not to speak of God’s judgment and mercy, but rather to contribute to the prison’s educational mission.

The NYPA soon named a new matron for Sing Sing’s female inmates, and Eliza Farnham (1815–1864) brought a new psychological approach. She relaxed rules in the women’s quarters, allowing conversation and popular novel reading. She also advocated phrenology and invited an artist to make drawings of inmates’ heads. It was rumored that she argued against preaching only Christian theology and stopped an assistant who tried to convert Catholic prisoners to Protestantism.

Order Christian History #123: Captive Faith: Prison as Parish in print.

Order Christian History #123: Captive Faith: Prison as Parish in print.

Subscribe now to get future print issues in your mailbox (donation requested but not required).

Chaplain Luckey and his wife, Dinah, took their concerns to the prison inspectors. According to former keepers in the women’s wing, Farnham had allowed public reading of Dickens’s novels, works by phrenologist George Combe, devotional pieces, travelogues, and her own memoir. This proved maddening to Dinah Luckey: a prisoner who came to the prison “deeply penitent,” Dinah claimed, became unconcerned about her eternal soul and captivated by notions of becoming a “fine lady” after three months of novel reading.

The NYPA, though, agreed with Farnham’s willingness to enlist a broader reforming arsenal in the interest of producing a virtuous citizenry. She won the battle over inmate education. Luckey lost his job.

Even as he ministered in other places (including New York’s notorious Five Points mission), Sing Sing stayed on Luckey’s mind. In 1853 he published Prison Sketches. The book included some inmate conversions, but they paled in comparison to the number of stories about bad prison staff, politics, insanity, false imprisonment, and despair. Although God’s grace was available in prison, many inmates failed to experience it. Convict life was awful, Luckey warned.

“Unearthly groans”

In 1855, when a Whig governor was elected, Luckey found a way back into Sing Sing. This time he spent less time trying to make the system better and focused instead on how good Christians could minister in an awful situation. Conditions were deteriorating; punishments ranged from solitary confinement and whipping to showering and yoking. In 1855 the New York Times reported on violent episodes at the prison including “the shaking of eight or nine hundred iron doors, and the unearthly groans of the men.”

In Prison Sketches Luckey told of an insane female inmate found, just weeks after her release, wandering New York with her Bible in one hand and shoes in the other. Luckey tried to find work for another discharged inmate hoping to lead a good life, but he was so impaired by prison beatings that Luckey could not help.

Luckey’s stories are classic warnings to the impenitent, but also commentary on the slim possibilities of redemption in Sing Sing as it was then administered. Prison Sketches includes only two hopeful stories, where successful outcomes rely on the intervention of benevolent Christians, not on regular prison routines.

Luckey depicted prisoners as fellow human beings who had done wrong, transformed by Sing Sing into subhuman wretches. Rescue from this hell was only available through benevolent Christians offering a tract, a dollar, some food, or a job. At the end of his memoir, the chaplain quoted a former inmate who wrote, “Heaven at last the wrong will right.”

Upon retirement Luckey moved to Missouri, but Sing Sing haunted him. When he died in 1876, his wife shipped his remains back to Ossining at his request. His body is buried on Sing Sing’s grounds. CH

This article is from Christian History magazine #123 Captive Faith. Read it in context here!

By Jennifer Graber

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #123 in 2017]

Jennifer Graber is associate professor of religion at the University of Texas at Austin and the author of The Furnace of Affliction.Next articles

Joys and challenges

What does prison ministry look like today? We Interviewed five individuals active in prison ministry to get first-hand accounts.

Jim Forbes, Christiana DeGroot, Joe Roche, Jack Heller, Susannah MooreCaptive faith: Recommended resources

Here are some recommendations from CH editorial staff and this issue’s authors to help you navigate the history of Christians in prison and Christians ministering to prisoners.

the editors