John Bunyan: The Man, Preacher and Author

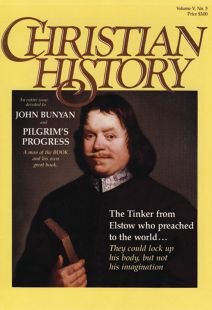

JOHN BUNYAN (1628-1688) was born at Elstow, near Bedford, England, the oldest son of a tinker. His education was undoubtedly slight. He acknowledged —in fact, he emphasized—his humble birth: “my father’s house being of that rank that is meanest and most despised of all the families in the land.” This was hardly inverted snobbery; it was a way of attributing solely to God credit for what he had become.

When he was sixteen, Bunyan was summoned in a county levy for the Parliamentary army. What active service he knew is uncertain; no significant battles were fought near Newport Pagnell, where he was stationed, and Bunyan makes no reference to any specific military engagements. After approximately three years, his company disbanded and he returned to Elstow and continued to work as a tinker. Bunyan was a lover of music but had little money for buying instruments. This lack failed to deter him: he hammered a violin out of iron and later carved a flute from one of the legs of a four-legged stool, which was among his sparse furnishings in his prison room.

He was married twice. His first wife, a person as poor as he, brought him a simple dowry of two well-known Puritan works, Arthur Dent’s The Plain Man’s Pathway to Heaven and Lewis Bayly’s The Practice of Piety. What the name of his first wife was, history failed to record. Four children were born to this marriage, including a blind daughter Mary. His second wife, Elizabeth, was a magnificently brave woman who stood in the face of hostility from the powerful and pleaded the cause of John Bunyan, especially when she feared he would be jailed for his preaching. Elizabeth and John Bunyan had two children.

Bunyan etches his spiritual progress in a series of imperishable vignettes. His first discovery of what Christian fellowship might mean comes when he overhears “three or four poor women sitting at a door in the room, and talking about the things of God.” Later he said: “I thought they spoke as if joy did make them speak; they spoke with such pleasantness of Scripture language and with such appearance of grace in all they said, that they were to me as if they had found a new world . . . .” Step by step, Bunyan found himself drawn into the fellowship of which these poor women were a part.

A few years prior to 1654, he meets, and is counselled by, John Gifford, minister of the open communion Baptist Church at Bedford. He moves from Elstow to Bedford and begins to preach in villages near Bedford. His ministry coincided with the Stuart Restoration of 1660 which meant that unauthorized preaching would lead to a punishable offense. Arrested in November 1660 for holding a conventicle (an illegal religious meeting), Bunyan was sentenced in January 1661, initially for three months, to imprisonment in Bedford jail. His continued refusal to assure authorities that he would refrain from preaching if released prolongs his imprisonment until 1672. During the imprisonment, authorities granted him occasional time out of prison, and church records show that he attended several meetings at the Bedford Church. In prison, he made shoe laces (to support his family), preached to prisoners, and wrote various works.

Bunyan’s first prison book was Profitable Meditations, followed by Christian Behavior, The Holy City, and Grace Abounding To the Chief of Sinners. From 1667 to 1672, he probably spent most of his time writing The Pilgrim’s Progress. This book, published in 1678, was for generations the work, next to the Bible, most deeply cherished in devout English-speaking homes. When the great missionary surge began, Protestants translated into various dialects first the Bible, then The Pilgrim’s Progress.

On January 21, 1672, the Bedford congregation called John Bunyan as its pastor. In March, he was released from prison—even though he spent six additional months in prison in 1677—and on May 9, he was licensed to preach under Charles II’s Declaration of Indulgence. During the same year, the Bedford church became licensed as a Congregational meeting place.

Bunyan’s dedication, diligence, and zeal as preacher, evangelist, and pastor earned him the nickname of “Bishop Bunyan.” Although he frequently preached in villages near Bedford, and at times in London churches, Bunyan always refused to move from Bedford.

Combined with his preaching and pastoral responsibilities was a heavy schedule of writing. Following the publication of The Pilgrim’s Progress (Part One), there appeared The Life and Death of Mr. Badman, The Holy War, an allegory less popular but perhaps more complex than The Pilgrim’s Progress. His last book—and he wrote more than sixty—was called A Book for Boys and Girls, published in 1686.

After riding on horseback in a heavy rain from Reading to London, Bunyan contracted a fever and died on August 31, 1688, at the home of his London friend, John Strudwick. He is buried in Bunhill Fields, London.

By E. Beatrice Batson, Ph.D.

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #11 in 1986]

E. Beatrice Batson, Ph.D., is Professor of English at Wheaton College, Wheaton, Illinois.Next articles

The Life and Times of John Calvin

As Shakespeare wrote, “Some are born great, some achieve greatness, and some have greatness thrust upon them.” John Calvin was certainly not born great.

Dr. T.H.L. ParkerSeeking a Better Way

The pain and damage of Christian divisions and international warfare affected Comenius and his church both directly and disastrously: His prodigious energy and gifts were obsessively employed to change the way the world and church worked.

Eve Chybova BockMoney and the Bible

A Survey of the History of Biblical Interpretation on money and wealth.

John R. MuetherAugustine’s Life and Times

Randall Petersen presents an overview of the great saint's life, from small-town hijinks to empire-moving ideas and encounters.

Randy Petersen