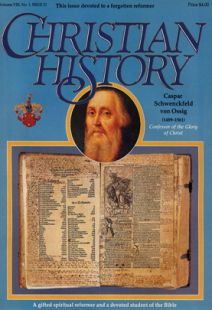

The Life and Thought of Caspar Schwenckfeld von Ossig

SOMETIME IN 1518, or perhaps 1519, Caspar Schwenckfeld experienced what he refers to as a “visitation of the divine” (in German, Heimsuchung Gottes, literally “home-seeking of God"). He admits that he was not particularly religious during his early years as a court advisor, but his pattern of behavior changed after 1518.

The visitation to which he refers was not the only change in his life at the time. He was directly affected by his reading of Luther’s writings, and he undertook a serious study of the Scriptures at this point in his life as well. Shortly before September 1519, his father died and not long after that Schwenckfeld began to lose his hearing, an event which forced him to return to his family estate at Ossig (now run by his brother Hans) and to serve Duke Friedrich as only an occasional advisor, although he did remain highly influential at the court.

By 1521 he was seriously supporting the cause of reform, and had won his Duke to his programme by 1522. But from the very beginning Schwenckfeld’s position seems to have differed from Luther’s, and by 1524 the differences were abundantly clear. In June of that year he published an Admonition to the Silesian preachers in which he attempted to rectify problems he saw arising from Luther’s theology. He was concerned above all that the five principles at the center of Luther’s position were misleading the simple people of the day. These were (1) that faith alone justifies, (2) that an individual does not have free will, (3) that we cannot keep God’s commandments, (4) that our works are of no avail, and (5) that Christ has made satisfaction for us.

The Nature of Faith

Ever concerned with the practical results of theology, Schwenckfeld did not reject these principles out of hand in his Admonition. Indeed, he had been initially drawn by their very “practicality” for the reform he supported. But by 1524, he had come to believe that if pressed too far, these keystones of reformation could prove ultimately destructive of their very intent.

To grasp the issue it might be best for a moment to stand back from the specifics of Schwenckfeld’s argument and look at the debate over the first principle, “that faith alone justifies,” in its full context. The traditional theology that Schwenckfeld had inherited had always taught that an individual is justified by grace through faith—that was a Catholic as well as a Protestant position. The problem arose in regard to the nature of the faith by which one is justified. Catholics in Schwenckfeld’s day (and ours) teach that justifying faith must be understood in the context of Galatians 5:6: “For in Christ Jesus neither circumcision nor uncircumcision is of any avail, but faith working through love."

It was this last phrase, “working through love,” which had led to the problems Luther pointed to. When simplistically interpreted by some theologians, this phrase had come to mean for many that the faith which availed was dependent on the acts of love through which it worked. Worse yet in the hands of ecclesiastical bureaucrats “works of love” came to be understood as the fulfillment of institutionalised religious regulations.

In this setting, one can understand both Luther’s and Schwenckfeld’s sense of release when they read Ephesians 2:8: “For by grace you have been saved through faith.” Here “faith” stood alone; the words “working through love” were missing, and the remainder of the verse emphasized the fact: “this is not of your own doing, it is the gift of God—not because of works.” Faith availed in itself for salvation and required no “working through love,” certainly not in the sense of keeping the particular rules set down in a code of church law, or by reciting formulaic prayers.

Unlike Luther, Schwenckfeld did not proceed to limit his theology by this insight (Luther’s so-called “canon within the Canon"). He was always more concerned with the results of a theological system on the life of individuals and the society in which they lived. He often spoke of his work as a “middle way” between what had become in the early sixteenth century two warring positions. Thus he would continue to uphold the need for Christian works of love while supporting what he considered the central insight of the Wittenberg Movement. The results were to be expected: He was viewed by both sides as supporting their opponents.

The Sacramental Center of Faith

Surprisingly enough, it was not over the issues noted in the 1524 Admonition that the real debate between Schwenckfeld and Luther erupted. To find a middle way between two opponents, as was the case in the so-called “faith-works” issue is one thing; it is quite another when a topic arises in which there are three conflicting opinions. This was the case regarding the Lord’s Supper.

By the middle of the 1520s this debate was already in full flower. Catholics maintained that when the priest elevated the bread at the altar and pronounced the words of consecration, the bread became the body of Christ (this position is called transubstantiation). The Swiss, under the leadership of Uldrich Zwingli, on the other hand, rejected such a position altogether and insisted that the bread merely represented the body of Christ. [See our earlier issue on Zwingli, Vol. 3, No. 1 for a discussion of Zwingli’s view of the Lord’s Supper.]

In a sense, in this disagreement, Luther’s position was the middle way. Those who followed him taught that more than simple representation occurred in the sacrament, but they rejected any interpretation which might lead one to think in terms of magical transformation. The body of Christ they taught, was “in, with, and under” the bread (called consubstantiation).

For Schwenckfeld all three explanations were unsatisfactory. Once again, what troubled him more than the divisive theologies of the Sacrament were practical results. Those who eat and drink of the body and blood of Christ unworthily, he believed with St. Paul, are “guilty of profaning” the body and blood (1 Cor. 11:27). What constituted unworthy participation more than doing so while anathematizing one’s fellow Christians? All three groups celebrated this central rite of Christian faith and unity while in open warfare with other Christians.

The situation was an open offence to the Faith, and Schwenckfeld was early concerned with it. He and his learned friend, Valentine Crautwald, had discussed the issue at length and the latter was greatly troubled over it.

Crautwald returned home after attending early communion on 16 September 1525 to consider the matter. After a full day of reflection he fell asleep for a short time and awoke before dawn on September 17. Suddenly all the passages of Scripture relating to the problem were before him, and a “sweet voice” opened them to him.

The vision he experienced and the ten days following it which were spent in detailed examination of its implications, he described in a letter to Schwenckfeld. Schwenckfeld in turn developed the results of the vision along with Crautwald.

The disputed words of institution should be read as follows: “My body is this, namely, food.” “It was not until the disciples had eaten the bread and drunk the wine that Christ spoke the words. Bread is not a food until the grain has been grown, threshed, ground, baked and eaten; bread when eaten nourishes and strengthens the body.” The word “is” in the words of institution means “is,” not “represents,” but one must distinguish between the physical and the spiritual. “Give the physical to the body, the spiritual to the poor soul which is spiritual; let physical bread nourish the physical body, the invisible [bread], the invisible soul."

By faith, then, one truly does eat the spiritual body of Christ, and in time Schwenckfeld and Crautwald would work out the implications of their theology, teaching that the spiritual grain thus eaten by faith grows in the believer, transforming him or her toward the full image of God, the person of Christ. On 30 November 1525 (two months after Crautwald’s vision), Schwenckfeld traveled to Wittenberg to present their findings to Luther. He was rebuffed by the great reformer, and from then on their paths would clearly separate.

The Suspension ("Stillsand") of the Sacrament

In spite of Luther’s rebuff, Schwenckfeld seems to have remained hopeful that his “middle way” might yet become a reality. He returned to Liegnitz and there with the aid of his duke and the brotherhood that had formed around him, worked avidly for the reform of the church in his area He supported the foundation of a university in Liegnitz and encouraged extensive catechetical work, both of theoretical and practical nature.

He also continued to write and speak on behalf of his explanation of the Lord’s Supper. But what of the practice of the Supper? Christians were still fighting with one another and now Schwenckfeld as well had entered the fray. On 21 April 1526 he, Crautwald, and the preachers and pastors of Liegnitz issued a circular letter reflecting the tension they then felt, and their solution for the impossible situation in which they found themselves.

"The fact of the matter is this: Since we and many others, including some of the populace, have felt and recognized that little betterment is resulting as yet from the preaching of the Gospel,” something must be wrong. And what could be more wrong than the improper celebration of the central Christian rite? “[Since this is the case,] we think that the Holy Sacrament or mystery of the body and blood of Christ has not been observed according to the Gospel and command of Christ.” Those who eat and drink unworthily, eat and drink judgement unto themselves, and therefore, “we admonish men in this critical time to suspend for a time the observance of the highly venerable Sacrament."

The suspension did nothing to ease tensions within Christendom; for the next four years the bulk of Schwenckfeld’s writing was directed to this issue. His duke, Friedrich II supported him, but as the heat of the reformation debate increased, Friedrich increasingly found himself in a dilemma. Politically it was necessary for the Silesians to draw closer to the Lutheran position, but with a counselor of so high a profile as Schwenckfeld expressing an anti-Lutheran position, this was difficult.

Finally in 1529, to avoid bringing his duke further embarrassment, Schwenckfeld went into voluntary selfexile. The most reasonable place for him to take refuge was the city of Strasbourg, then undergoing a reform under the direction of Martin Butzer.

Time in Strasbourg

Strasbourg was remarkably tolerant for the time, and as a result attracted persons of widely differing religious opinions. It was here, for example, that Schwenckfeld met the Anabaptist Pilgram Marpeck with whom he would enter a lengthy debate in the 1540s. It was also here that he seems to have come to know the thought of Melchior Hofmann, whose position on the celestial body of Christ had much in common with his own, although he always maintained that Hofmann had borrowed ideas from him and not he from Hofmann.

Although he maintained a peaceful tone in the debate at the time, Schwenckfeld held a firm debating position. He supported his ideas with learning and care, and he did attract enough followers that his opponents were forced to take him seriously (his position as a member of the nobility also seems to have required this).

Nevertheless, his point of view was a minority one during the period and was never supported by a powerful political leader. What this meant was that he was ever forced to debate without the possibility of winning. That pattern would remain throughout his life. We must take care not to romanticize the results. Like other supporters of unpopular theological positions at the time, Schwenckfeld undoubtedly suffered persecution, and it is clear that he never settled permanently in one place for the rest of his life. However, he was able for significant periods of time to find the physical stability necessary for the study and production of his numerous theological treatises and letters.

Confessor of the Glory of Christ

In 1541 he was living near the south German town of Kempten and had for his use the library of the Benedictine monastery there. It was here in the same year that he completed his longest and most complex work, The Great Confession on the Glory of Christ. Schwenckfeld’s thought on the nature and person of Christ was fully developed by 1538 at the latest, but he had been reflecting on the question from his earliest writings on the sacrament in the 1520s. What he was ever concerned with was that the body of Christ not be disparaged, or, to put it positively, that the glorified body of Christ be properly confessed.

Because Schwenckfeld’s christology was not accepted by his contemporaries or later generations (indeed, it was considered heretical by many), it continues to be noted as one of the most “peculiar” aspects of his thought. But, peculiar or not, it was the center-point of his work, and, in honor of this core doctrine, his followers continued to call themselves “Confessors of the Glory of Christ” until the eighteenth century. The obscure theological details and their source in the writings of the early church need not detain us at this point. Simply put, Schwenckfeld distinguished two natures (a divine and a human) in the person of Christ, as does Christian orthodoxy. But he thought of the human nature in terms of a “celestial flesh.” Jesus’ flesh, he taught, was increasingly divinised by his divine nature during his earthly sojourn, so that it was transfigured and thereafter resurrected, taken up, and glorified at the right hand of the Father. It is on this glorified flesh that the believer feeds by faith; it is this flesh which by faith believers spiritually partake of, and which, in turn, grows like a grain of mustard in them as they grow daily in the image of Christ.

Whatever one might think of Schwenckfeld’s christology today (whether it can be defended or not as orthodox as he thought it could) is a separate question. What we need to understand is Schwenckfeld’s intention in developing such a doctrine. He never thought simplistically or literally. The glorified body of Christ which sits at the right hand of the Father is the body of which one partakes in the Sacrament. It is not to be separated from the body of Christ in which believers live and move and have their being and which they call by the name “Church."

Thus one eats and drinks judgement upon oneself, according to I Corinthians 11:29, when one eats and drinks of the body and blood of Christ in the Lord’s Supper “without discerning the body"; “body” here referring to the bread which is the spiritual body of Christ—the community of believers throughout the world, or the Church—and referring to the glorified body of Christ itself.

By approaching the sacrament without discernment—without recognizing that the Church is the universal (catholic) body of Christ, and not merely the physical social-political entity made up of those who hold particular doctrines in common against others—one disparages the Glorified Christ.

Looking Above for Peace

It was for this reason that Schwenckfeld so strongly opposed the Anabaptist Pilgram Marpeck. Marpeck and the Anabaptists (later Mennonites) attended to the historical Jesus of Nazareth. Schwenckfeld was not opposed to this attention and certainly not to the Anabaptists’ attempt to imitate the life of the earthly Jesus. What he asked of them in addition was that they “lift up their hearts” to the image of the Glorified Christ so as not to become only caught up in concerns for purity of their local and limited congregational life.

And the theology of the Glorified Christ is also the context in which Schwenckfeld’s often-noted concern for religious toleration arises. His is not a political position (as is that of, for example, the American Constitution); it is a theological one. One confesses the glory of Christ not by supposing that all religious opinions are of equal value, and effectively holding that they are makers of taste and that in such maker one person’s opinion is as good as another’s.

For Schwenckfeld religious toleration depended not on looking below oneself but on contemplating above one’s possibilities:

Only when all believers had raised their sights to the One above all others, would the suspension of the sacrament come to an end in reality, a hope toward which he reached throughout his life, and for which he still yearned, we are given to understand, when he died in the home of friends in the city of Ulm in 1561.

By Peter C. Erb

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #21 in 1989]

Next articles

An Ancient and Undying Light

The Waldensians from the 12th Century to the Protestant Reformation.

Dr. Giorgio Bouchard.Awakenings in America: Seasons of the Spirit

Spiritual awakenings have brought lasting benefits to the Church and the surrounding culture. Have we forgotten our great heritage of renewals?

the EditorsA 12th Century Man for All Seasons The Life and Thought of Bernard of Clairvaux

Bernard's life and teachings have a persistent appeal and timeless meaning and value.

Tony LaneThe Life & Times of D. L. Moody

How an awkward country boy with a grade-school education became the greatest evangelist of the Gilded Age.

Dr. David Maas