Nozrim and Meshichyim

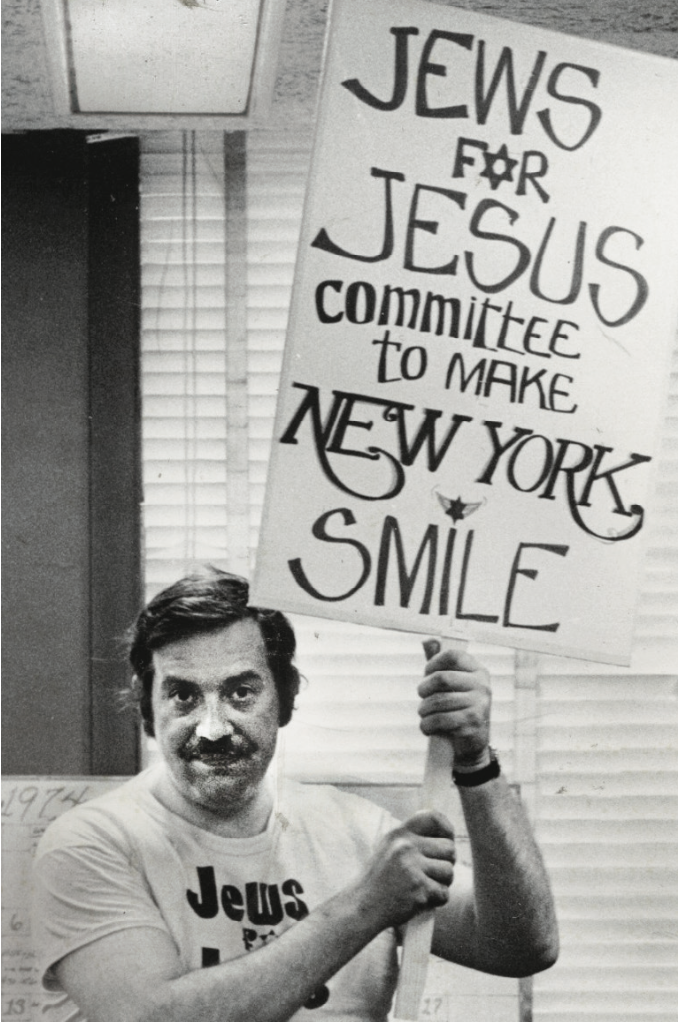

[MOISHE ROSEN IN THE 1970S—© JEWS FOR JESUS]

Messianic Judaism combines faith in Jesus as Lord and Savior with Jewish identity, culture, symbols, and rites. Until the 1970s even those Jews who accepted Christianity and created what they called “Hebrew Christian” congregations, retaining some Jewish customs, mostly rejected such a combination. Today Jews, Christians, and Messianic Jews wrestle with the uniqueness of the movement.

Baby boomers and Jews for Jesus

Missionaries and communities of Hebrew Christians in Israel noted in the mid-twentieth century that for Israeli Jews, the term Nozrim (Hebrew for Christians) meant an alien, if not hostile, religion. In contrast, Meshichiyim, meaning Messianists, held an aura of hope, emphasizing the Messianic element of the faith. Especially among themselves many Messianic Jews identified as Maaminim, “Believers” (in Jesus). In recent years many have preferred the more inclusive “Jewish Believers in Jesus,” which includes all Jews who accept the Christian faith and remain connected to their Jewish roots, regardless of their communal affiliation.

The term “Messianic Jew” resurfaced in America in the early 1970s; a vigorous and assertive movement formed out of American Jews who had accepted Jesus as their Savior. Members of the Baby Boomer generation filled these new communities; as in other forms of Boomer religion, Messianic Judaism sought to put together elements that previous generations had considered to be in contrast to each other.

At the same time, many religious and ethnic groups of the 1970s were taking greater pride in their roots, and evangelical Christianity—where Messianic Judaism found its home—was beginning to offer more space for ethnic, cultural, and linguistic differences. Israel’s defeat of its Arab neighbors in June 1967 strongly affected evangelical attitudes. Evangelicals developed growing appreciation for Jews, whom they saw as playing an important part in the events leading to Jesus’s Second Coming. Some evangelical churches began to include Jewish symbols and customs in their worship. Likewise the 1967 war boosted the desire of Jews who joined Christian churches to maintain Jewish identity and culture. Many Messianic Jews and their evangelical Christian supporters felt that they were working to heal old wounds and bring together two religious traditions they believed should never have been at odds.

Messianic Judaism was not the only attempt at this collaboration. Jews for Jesus, founded by Moishe Rosen (1932–2010), quickly became one of the more energetic evangelical-Jewish groups of the early 1970s. Jews for Jesus was an explicitly Christian-Jewish missionary organization; Rosen related skeptically to Messianic Jewish congregations. He asked his missionaries to join non-Jewish churches and to direct inquirers and converts to such churches. Later on the movement did establish Messianic congregations.

Another group resembling Messianic Judaism is the Hebrew Catholic movement. The group has a handful of churches in Israel, as well as mostly virtual communities elsewhere. Hebrew Catholics follow Catholic liturgy and theology; at the same time, they have written their own prayers, bringing Catholic elements of faith together with Israeli culture, such as Hebrew hymns for Miriam HaMevurahat (Mary). The Vatican recognizes the movement and created the Vicariate of St. James in 2011 for Hebrew congregations in Israel.

Old and New Testaments

Despite the growing visibility of Jewish believers in Jesus in the 1970s, most Jews did not accept the claim that one could embrace Jesus as Lord and Savior and remain within Judaism. Some considered the new movement to be a missionary ploy to lure Jews away from their ancestral faith. Others viewed it as a harmful cult. On rare occasions Jews turned to violence against Messianic Jews—defacing sanctuaries or harassing individual members.

Today some Jews continue to feel negatively about Messianic Judaism, while others call upon fellow Jews to accept Messianic Jews as part of the larger Jewish community. Some liberal Protestants have also expressed reservations about Messianic Judaism, largely because of the movement’s association with conservative evangelical tenets and views; they object to its theology, its interpretation of Scripture, and its support for right-wing politics. As a rule evangelicals do not promote interfaith dialogue, but they see their acceptance of Messianic Judaism as a way of recognizing Jewish tradition.

Messianic Jews embrace the major premises of evangelical theology, including the principle that all people need to undergo personal experiences of conversion and accept Jesus as their Savior. They promote traditional evangelical morality and embrace a strict work ethic and obedience to the law. They also typically see special merit in sharing the gospel with fellow Jews, instructing them in how to read the Bible along evangelical lines, and bringing them to accept Jesus as Savior.

Messianic Jews study both the Old and New Testaments, regarding both as historically accurate and prophetically revealing. They share the premillennialist evangelical belief in the imminent return of Jesus to establish the Kingdom of God on earth and in the dominant role of the Jews and Israel in bringing about the Messianic times.

Even while adhering to evangelical principles, the founders of Messianic Judaism desired independence from the Protestant denominations or missionary societies that had traditionally aimed at making Jews into Protestants. However, missionary societies such as Chosen People Ministries have helped to create self-standing Messianic Jewish congregations since the 1980s. Such communities serve as centers of evangelism for Jews and non-Jews alike. By the turn of the twenty-first century, the majority of members in Messianic Jewish congregations had not grown up in Jewish homes (though many claimed Jewish ancestry or were married to partners of Jewish descent). More than 400 Messianic communities exist in America and over 100 in Israel, with dozens more in Europe, Latin America, South Africa, and Australia. Tens of thousands of people are members of Messianic congregations and tens of thousands more consider themselves Messianic Jews, or Jewish Believers in Jesus, even if they are members of mainstream churches. There are now significant numbers of second- and third-generation Messianic Jews.

Major divisions do exist in practice and interpretation. One is between charismatics, who advocate a direct personal encounter with the divine and practice expressive modes of worship, and noncharismatics, whose prayer is more traditional and formal. Most early congregations chose to become charismatic, but later ones were established by mostly noncharismatic missionary societies.

Congregations reflect a broad spectrum of observance of Jewish traditions and rites and put different Jewish and Christian liturgical elements together. Most congregations conduct their weekly prayer meetings on Friday nights or Saturday mornings, and they often ask male members and guests to wear yarmulkes during the services. They have installed arks with Torah scrolls and read a passage from the parasha, the weekly Jewish reading from the Pentateuch.

Messianic Jews have incorporated Israeli songs and the use of modern Hebrew into their services. Their attachment to Israel has come to signify devotion to Jewish causes as well as a premillennialist understanding of the role of Israel in God’s plans.

Yeshua the savior

While struggling to be accepted as both genuinely Jewish and authentically Christian, Messianic Judaism has built its own subculture—national organizations, youth movements, conferences, retreats, prayer books and hymnals, websites, periodicals, and theological, apologetic, and evangelistic treatises.

Many Messianic hymns resemble contemporary evangelical ones, but refer to Yeshua, Jesus, as the Savior of Israel. Messianic Haggadot (Passover services) and siddurim (prayer books) include elements of traditional Jewish liturgy, replacing certain passages with prayers expressing faith in Jesus as Redeemer. The embrace of bar mitzvahs serves as a statement that Messianic Jews still practice Jewish culture, albeit with a Messianic focus. Instead of the conventional haftarah (prophetic reading), Messianic bar mitzvah boys often read from the New Testament, and the drasha, a customary bar mitzvah sermon, is often a public declaration affirming Messianic Jewish faith and identity.

Most Messianic Jewish writers claim the antiquity of their movement, emphasizing that the earliest Christians were Jews. David Stern (b. 1935), a leader in the Messianic Jewish movement in America and Israel, edited a Messianic Jewish New Testament in which he changed the name of the Epistle to the Hebrews to Letter to the Messianic Jews. In his Messianic Jewish Manifesto (1988), Stern asserts that Messianic Jews are not 50 percent Jewish and 50 percent Christian, but rather 100 percent Jewish and 100 percent Christian.

The early twenty-first century has seen a new generation of Messianic Jewish intellectuals with new interpretations of the movement. For example Israeli Gershon Nerel (b. 1952) advocates relying solely on the Scriptures as a source of authority instead of Protestant theology or creeds. Mark Kinzer (b. 1952) of Post-Missionary Messianic Judaism and the group Hashivenu (Bring Us Back), advocates cutting the cord between Messianic Judaism and the missionary community, basing theology on Jewish postbiblical sources. While still committed to some basic elements of evangelical theology and devoted to Jewish identity and heritage, Messianic Jews are now becoming more autonomous, creating theological and communal spaces of their own. C H

By Yaakov Ariel

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #133 in 2020]

Yaakov Ariel is professor in the department of religious studies at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and the author of Evangelizing the Chosen People, On Behalf of Israel, and An Unusual Relationship: Evangelical Christians and Jews among other works.Next articles

Experiencing Messianic Judaism

Paul Phelps“Our Jewish life”

Jewish thinkers, writers, leaders, and artists with lasting impacts

Jennifer A. BoardmanSorrow and blessing

Two theologians seek to illuminate the difficult history in this issue

Ellen T. Charry and Holly Taylor CoolmanChristianity & Judaism: Recommended resources

Recommendations from our editorial staff and this issue’s authors to help you navigate the history of Christian-Jewish Relations.

the editors