Our scattered leaves

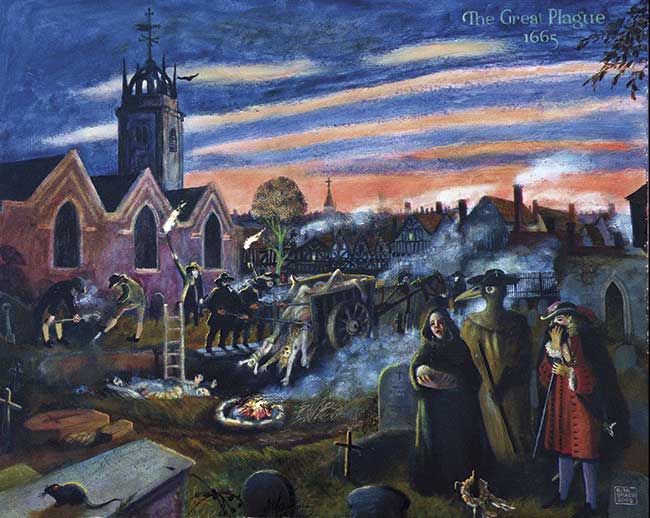

[Rita Greer, The Great Plague 1665—Wikimedia]

On march 12, 2020, our local theater was preparing for the second weekend of our production of Bertolt Brecht’s The Good Person (often known as The Good Woman of Szechuan). Attendance the first weekend had been sparse, and we were hoping for better results this time around. But it became clear in the course of the evening that at least half the cast had serious misgivings about going forward in light of the unfolding coronavirus pandemic. We canceled the play. Soon the governor of Kentucky would close schools and theaters as well as other places where large groups gather. Ironically, love of neighbor cut us off from our neighbors.

No one is an island

In 1623 a disease that contemporaries called the “spotted fever” or “relapsing fever” swept through London. Some modern scholars believe that it was typhus. Among the sufferers was dean of St. Paul’s Cathedral John Donne (1572–1631), then in his early forties. While recovering he wrote a series of meditations, one for each of the 23 days he had been sick, and published them the next year as Devotions upon Emergent Occasions. The most famous is “Meditation 17,” which contains two phrases that have become clichés: “No man is an island” and “Never send to know for whom the bell tolls; it tolls for thee.” “Meditation 17” is one of the most eloquent and concise examples of a very old Christian genre: writing inspired by the threat of death, specifically death from infectious disease.

Plagues of various kinds were a common feature of life for most of human history before the development of vaccines and antibiotics. Particularly in times of population growth and urban development, the crowded and unsanitary conditions in which most people lived fostered frequent and devastating epidemics. In traditional Christian societies, these epidemics were typically seen as expressions of God’s wrath against human sinfulness.

Care for plague victims had been an important part of Christian discipleship from the very beginning. Early Christians gained moral authority in the ancient world because they cared for their own sick and even for victims outside the Christian community. Basil the Great pioneered hospitals, and the medieval church developed these institutions further—though often they were what we would now call “hospices,” where the dying were made comfortable, rather than institutions that could actually cure diseases.

Catholics and Protestants alike in the early modern period called for fasting and prayer in response to plagues. Clergy were often judged by their response: while fleeing plague might be justifiable under some circumstances, people in positions of spiritual authority who fled too readily and failed to care for the sick were criticized, while those who remained and risked their lives were seen as heroes.

At the same time, what we are now calling “social distancing” was also a reality. Charles Borromeo (1538–1584), bishop of Milan in the late sixteenth century, closed churches but organized open-air celebrations of the Mass which people could watch from their windows, because for Catholics simply seeing the consecrated host was believed to be of great spiritual value.

He sent priests from door to door to give communion and hear confessions, putting the clergy at risk while attempting to minimize the danger of transmitting the disease. As a result, even though normal public worship was interrupted, the city was, in the words of one Catholic author, transformed into something like a monastery.

Binding up scattered leaves

As contemporary commentators have pointed out, the present crisis calls us to think about the common good and find ways to practice solidarity while physically distancing ourselves. Donne is 400 years ahead of us. His famous remark about the bell tolling for everyone is not just a reminder that we are all mortal. It affirms our solidarity as members of the human race and, for Christians, as members of the church:

The church is catholic, universal, so are all her actions; all that she does, belongs to all. When she baptizes a child, that action concerns me; for that child is thereby connected to that head, which is my head too, and [engraved] into that body, whereof I am a member. And when she buries a man, that action concerns me; all mankind is of one author, and is one volume; when one man dies, one chapter is not torn out of the book, but translated into a better language; and every chapter must be so translated; God employs several translators; some pieces are translated by age, some by sickness, some by war, some by justice; but God’s hand is in every translation, and his hand shall bind up all our scattered leaves again, for that library where every book shall lie open to one another.

“No man is an island”—not just because we are all interconnected in our existence on this planet, but because we as Christians have been “grafted” into the body of which Christ is the head. In baptism we have already died and risen with Christ. And thus the death, and the hope of resurrection, of every other Christian—and indeed of every other human being created and redeemed by the divine Logos—is ours too.

Donne plays on the still-current sense of translating from one language to another as well as the now archaic sense of the word as a euphemism for death. (The King James Version uses the term for Enoch’s deathless transition from this life to the life to come.) Now we speak different languages, not just in the literal sense but in far more painful and divisive senses. But God’s ultimate purpose is to “translate” us into the language of his kingdom, in which we will all be intelligible to each other.

One of the ironies of the pandemic is that we must express our solidarity with one another by limiting our physical interaction. But the related paradox is that the Internet, which so many of us have long deplored as a cold substitute for real human interaction, has become a vital means to express that solidarity. It is not the same as seeing and touching one another, and God help us if we forget that. But it does, at its best, foreshadow the heavenly intertextuality to which Donne points us.

I can hear and empathize with the anguish of people who are being touched by this virus in ways that my family and I have not yet been touched. And people who are living closer to the front lines can warn the rest of us. Yes these warnings can cause anxiety and fear, and the Internet can become a toxic, demonic force. But it can also be a means of grace, a means of affirming our solidarity as peninsulas of that great continent centered on the point where heaven touches earth in the Incarnate Word. CH

By Edwin Woodruff Tait

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #135 in 2020]

Edwin Woodruff Tait is contributing editor at Christian History. This originally appeared as a blog post on our website.Next articles

“The Lord brought all this dying”

"Some of our friends are dying others flying" from yellow fever

Barton Price“The sickness of others”

The flu pandemic of 1918–1919 swept through crowded neighborhoods.

Janine Giordano DrakeE. Stanley Jones: Did you know?

From a poor Baltimore childhood to friendship with Gandhi, E. Stanley Jones had a remarkable life

Robert G. Tuttle Jr.