Plagues and epidemics: Did you know?

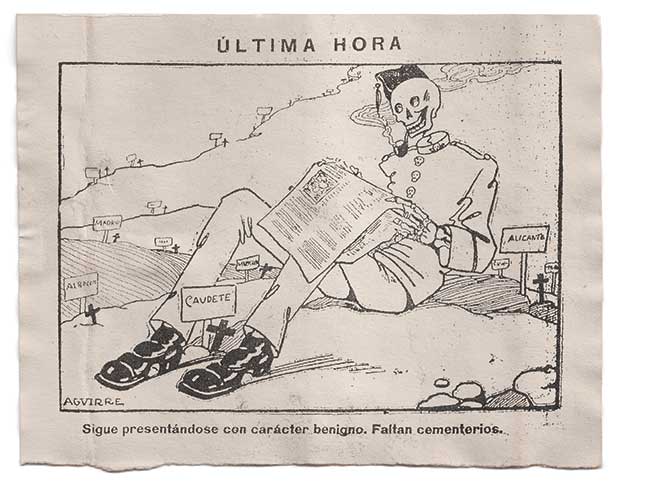

[Cartoon describing "Spanish" flu]

The “little lad”

The remote Jarrow monastery in England was newly founded when plague hit in 686. Every monk succumbed except Abbot Ceolfrid and a “little lad,” ward of the monastery. Most scholars identify the lad as the Venerable Bede. The young survivor was ordained a deacon at the uncanonical age of 19, became master of education at Jarrow, and composed his famous Ecclesiastical History around 731.

40 days of quarantine

Ragusa (modern Dubrovnik, Croatia) gave us in 1377 the first relatively effective method of dealing with the Black Death: quarantine—isolating ships and travelers from plague-infected areas. Derived from the Italian for “forty days,” quarantine’s length may have been influenced by Lent, the length of the biblical flood, or Christ’s wilderness isolation.

Plagued city

Plague outbreaks were the greatest and most persistent killers in European port cities for centuries. Venice, crossroads of Europe and the Mediterranean, and a major participant in endless disease-spreading military conflicts, was no exception. Between 1456 and 1528, it had 22 outbreaks, leading it to create a Magistrate for Health in 1485, which became one of the most powerful agencies of the Venetian state. The Magistrate supervised the food industry, barbers, physicians, waste disposal, sewage, water management, mortuaries, and lazaretti (isolated stations for leprosy victims, used to quarantine plague sufferers).

Beaks for quacks

From the Middle Ages through the nineteenth century, plague victims were often treated by plague doctors, considered quacks even then. Their distinctive beaky mask (see p. 22) was developed in the seventeenth century by Frenchman Charles de L’Orme in keeping with an odor-based theory of disease. The beak held sweet-smelling flowers and perfumes thought to banish infections.

Almost dead before he could begin

In 1832 Charles Finney (1792–1875) left his famous itinerant evangelism to accept a call to New York’s Chatham Street Church. He became ill with cholera in the middle of his installation service; others who contracted the disease that same day died. Finney’s life hung in doubt for days, but he lived, although so weakened it would be months before he could take up full duties.

Opportunities of usefulness

Anthony Norris Groves (1795–1853), a dentist and member of the Plymouth Brethren (see CH #128), went as a missionary to the Middle East at his own expense. In 1830 he explained why he and his family remained in Baghdad despite plague: “In the first place, we feel that while we have the Lord’s work in our hands we ought not to fly and leave it; again, if we go, it is likely that for many months we cannot return to our work, whereas the plague may cease in a month; opportunities of usefulness may arise in the plague that a more unembarrassed time may not present; and our dear friends from Aleppo may come and find no asylum.” He lost his wife, Mary, to the plague the following year.

What’s in a name?

Though the pandemic of 1918–1919 is commonly referred to as the “Spanish Flu,” it did not start in Spain. But since Spain was not engaged in the First World War, it was not under wartime censorship and could report on the disease, creating the impression that it was particularly affected. The name stuck. CH

Entries on quarantine, Venice, plague doctors, and the 1918–19 pandemic are by Paul E. Michelson, distinguished professor of history, Huntington University. Entries on Finney and Groves, by Dan Graves, are adapted from our website’s “This Day in Christian History.” The entry on Bede is by Frank A. James III, president of Missio Seminary, and is adapted from issue #72.

By Paul E. Michelson and others

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #135 in 2020]

Paul E. Michelson distinguished professor of history, Huntington UniversityNext articles

Editor's note: Plagues and epidemics

Every year this plague issue would get kicked down the road as other issue concepts rose in priority.

Bill CurtisThe plagues that destroyed

A survey of epidemics and some Christian responses

Darrel W. Amundsen and Gary B. Ferngren