The Reformation Era

AN OLD ADAGE SAYS, “To the victors belong the spoils.” In no place does this prove truer than in the writing of history. History has most often been written from the point of view of the winners, not the losers. For this reason the writing of the history of the reformation era has always caused difficulty.

Indeed, until the beginning of this century there were few studies of the Reformation not written either from the point of view of the victorious Catholics in the south and east of Europe, or from that of the Lutheran and Reformed church Protestants in the north. And for both these groups, those reformers such as Schwenckfeld, now referred to as Radical Reformers, were represented negatively. Designated as Schwaermer (German for “swarmers”) they were considered to be foolish, impatient revolutionaries with erratic theologies of little interest to anyone. They rightly deserved to be forgotten. If their memories were maintained at all, it was to secure images of what was not to be thought or done.

As Reformation studies have progressed, however, it has become clear that such a designation is far too simplistic. The Reformation of the early sixteenth century was not a single unified movement that clearly ascertained the evils of a corrupt institution, determined the best approaches to eradicate them, and moved resolutely in one direction to do so. It was a period not of one reformation, but of many.

At least 25 years before Luther posted his 95 theses, loyal adherents of the traditional faith were working to reform the Church from within. They deliberately chose to work under the episcopal system. The Reformation they inaugurated is today referred to as the Catholic, or Counter Reformation.

With Luther and the Reformed Church movement of the Swiss, the structural framework of reform was shifted. Insisting that there was a need for the reform of doctrine as well as morals, these protesting groups sought support from their local political rulers (magistrates): they sought to carry out their reform with the support of the secular state. As a result it has become customary to refer to these groups (i.e., Lutherans, Zwinglians, Calvinists, and in some sense the Church of England) as the Magisterial Reformers.

There were, however, large numbers of Reformers who do not fit either of these patterns. They worked for the most part as individuals or as separatistic local congregations and they differed as much among themselves as they did from the major Catholic and Magisterial Protestant movements.

Categorized generally under the rubric “the Left Wing of the Reformation,” or more recently, “the Radical Reformation,” they can be divided into four general groups.

The first group sought to bring about the Kingdom of God on earth by the sword and is suitably referred to as Revolutionary. To this group belonged Thomas Müntzer and the Anabaptists who took control of the city of Münster where they were stopped by military force in 1535.

A second group, termed Anabaptists (the ancestors of present-day Mennonites, Amish, Hutterites, and the step-parents of modern Baptists) were small groups who were committed to the peaceful establishment of the Kingdom of God.

The third, an assemblage of rationally oriented thinkers, saw the Kingdom of God as manifest—and manifested—in that spark of the divine in every human person.

Schwenckfeld is perhaps the best representative of the fourth Radical reformation group, the Spiritualists. He and others who are placed in this category tended to make a sharp distinction between spirit and flesh, the spiritual words of the Scripture and the physical letters, the spiriual-invisible universal Church and the physical institutionalized forms of Christianity, the spiritual sacraments and the bread or water.

However, one must always take care not to make too sharp the distinctions between these different groups. The peace-loving and pacifistic Anabaptist Menno Simons had a brother, it is said, who joined the revolutionaries. The Anabaptist Pilgram Marpeck had much in common with his opponent Schwenckfeld. And although the Radicals tended to see themselves as joined theologically for the most part with the Magisterial Reformers, most of them held to a view of grace and free will distinctly at odds with that of Luther.

History has most often been written from the point of view of the winners. Luther, Calvin, and other larger-than-life characters have dominated our books on the Reformation. Our interest in them is not misplaced; it is certainly based on the great roles they played.

But the Reformation was much more. And in the tumult of that colorful and complex era we have overlooked and forgotten people whose lives and ideas hold a significance we may have only slightly appreciated.

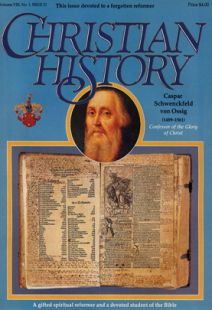

Caspar Schwenckfeld is such a character. His name, which will sound odd to most, has been usually relegated to footnotes, or mentioned with little explanation of who he was or what he believed.

Yet, fortunately, when God surveys his people as they quickly pass across the stage of history, he sees what our pages cannot record—what is in their hearts. From our pride we have presumed to declare the winners and the losers. CH

By the Editors

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #21 in 1989]

Next articles

The World of Schwenckfeld’s Birth

Take a trip in a time machine back to Schwenckfeld’s time.

the EditorsThe Germanic States Before the Seventeenth Century

A list of eight German states of the sixteenth century.

the EditorsJourney to Wittenberg

In late November 1525, Schwenckfeld traveled almost 100 miles on horseback from Liegnitz to Wittenberg the fountainhead of the reform movement, and met with Martin Luther and some of his Wittenberg colleagues.

the Editors