Seeking other Edens

Four years ago I entered paradise. Driving up the steep and twisted road with sheer mountain slopes on either side, we finally rounded a sharp bend, and the valley opened out before us. Yosemite Valley is seven miles long and a mile wide, a fabulously fertile, temperate, and remote garden with a river running through it, encircled by peaks and precipitous rocky slopes. No wonder the Native American tribe the Ahwahnechee once made it their home.

Four years ago I entered paradise. Driving up the steep and twisted road with sheer mountain slopes on either side, we finally rounded a sharp bend, and the valley opened out before us. Yosemite Valley is seven miles long and a mile wide, a fabulously fertile, temperate, and remote garden with a river running through it, encircled by peaks and precipitous rocky slopes. No wonder the Native American tribe the Ahwahnechee once made it their home.

The first encounter between God and humans in Genesis 1 occurred in just such a place of abundant provision. In earthly paradises such as Yosemite, humans glimpse the divine generosity that was part of God’s original plan for creation.

In Genesis God commands on the third day, “Let the earth put forth vegetation: plants yielding seed, and fruit trees of every kind on earth that bear fruit with the seed in it.” Then God tells humans on the sixth day, “I have given you every plant yielding seed that is upon the face of the earth, and every tree with seed in its fruit; you shall have them for food.” Gardens, orchards, and fields have been part of God’s plan for our world since the beginning.

grain, grapes, and olives

In the Bible food growing was a major occupation. The primary staple was grain in the form of wheat, barley, flax, and spelt (Exodus 9:31–2). Barley was considered the poor person’s grain because it tastes worse than wheat (to most folks) and is harder to digest. When used in baking, barley flour rises less well, and so this grain costs about half the price of wheat. However it can be sown in harsher conditions, requires less water, and can be harvested earlier.

It is at the barley harvest that we encounter the Moabite Ruth and her Hebrew mother-in-law, Naomi, migrants into Israel, who follow harvesters to glean the remains of the crop. Boaz’s salutation to the women, “The Lord be with you” (Ruth 2:4), is now the priest’s greeting to the people at the Eucharist, rooting our worship exchanges in real-life growing and gathering of food.

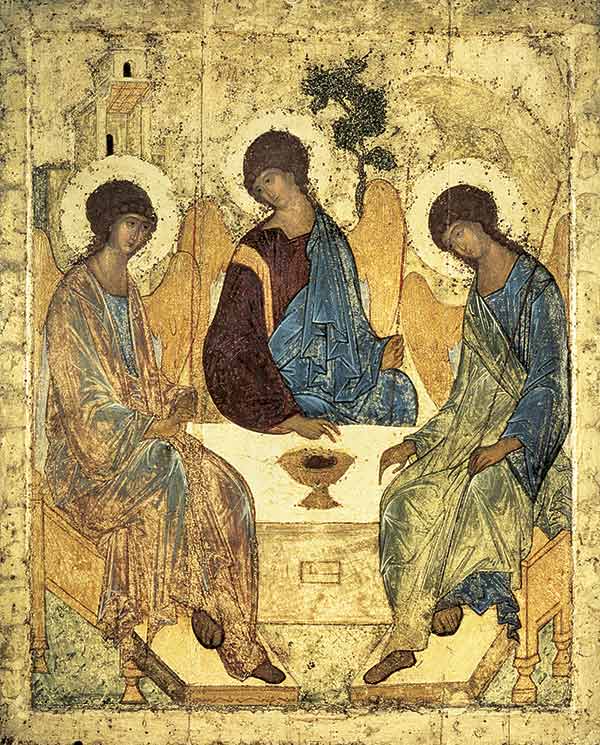

And let’s not forget the fruit of the vine, the second element of the Eucharist. Grapevines were cultivated as early as Noah’s day, the Scriptures say, presumably by training on vertical supports such as trees, or by being allowed to spread at ground level.

During the Exodus when the Israelites were camped in the desert, spies were dispatched into the promised land to survey its trees and farms. They cut down a single huge cluster of grapes and marched back with it hanging on a pole carried between two of them (Num. 13:17–24), displaying to all the lush provision that God had in store for them. Vineyards represent a considerable investment of time and money. And New Testament parables describe how they were staffed by both family members and casual workers, and might be rented out to tenants (Matt. 20:1–16, 21:28–44).

Another staple was olives and the rich oil they produce. Beyond cooking and baking, olive oil was used for religious offerings, the ritual of anointing, and even lamp fuel.

The importance of the last of these is shown in the parable of the wise and foolish virgins: those with oil in their lamps were ready to go out to meet the bridegroom when he came at midnight, whereas the unprepared could not and so missed their chance (Matt. 25:1–13).

To combine strong roots with large fruit and disease resistance, trees were cultivated by grafting the stems of one variety onto the rootstock of another. Paul the apostle was familiar with this operation, using it as an image for bringing non-Jews into the church (Rom. 11:17–24).

There are still olive groves close by Jerusalem, overlooking the Temple Mount and the Kidron Valley, and Jesus went to these very hills following the Last Supper (Luke 22:39).

apples, nuts, and roots

Despite the strong biblical witness to stable agricultural communities, Christian hermits in the early days of monasticism followed the lead of John the Baptist, embracing a far more precarious relationship with food. Rejecting the comparative security of farming, they gathered food as they found it. For example, in the life of the sixth-century Irish monk Brendan of Clonfert (c. 484–c. 577), a monastic community at Mernoc is described as eating only “apples and nuts, and roots of such kinds of herbs as they found.”

Yet the earliest monasteries recognized that foraging robbed the community of time for tasks such as prayer, study, and manual labor. To supply their needs, many monasteries planted gardens. These ensured a stable supply of required foods. In the very first-known monastic community, centered on Coptic hermit and abbot Pachomius (c. 290–346), crops included corn, olives, and herbs, which were used both as food and as medicine.

However, produce could not simply be taken and consumed at will. Around 320 Pachomius compiled the earliest monastic rule, directing that “no one shall take vegetables from the garden unless he is given them by the gardener.”

Monks were to exercise similar personal restraint while on their monastery’s agricultural land. “For the sake of discipline,” Abbot Pachomius wrote, “no one should dare eat still unripe grapes or ears of corn. And no one shall eat at all anything from field or orchard on his own, before it has been served to all the brothers together.”

Pachomius also censured indulgence practiced by those responsible for the community’s prized date palms. “The one in charge of the palm trees,” he instructed, “shall not eat any of their fruits before the brothers have first had some.” He continued:

Those who are ordered to harvest the fruits of the palm trees shall receive a few from the master of the harvesters to eat on the spot. And when they have returned to the monastery, they shall receive their portion with the other brothers.

Pachomius even laid down rules for how the brothers should handle windfall: If they find fallen fruits under the trees, they shall not dare to eat them, but they shall put them together at the foot of the trees as they pass by. Also the one who distributes the fruits to the other harvesters may not taste them, but shall bring them to the steward who shall give him his portion after he has given some of them to the other brothers.

grow local, shop local

As communities of monks sharing a common life developed, the stable food supply suggested by Pachomius’s rule became the norm. A key principle was that the foods communities ate should be locally produced.

In his monastic rule composed around 350, Basil of Caesarea (330–379) directed: “We ought to choose for our own use whatever is more easily and cheaply obtained in each locality and available for common use.” Basil was alert to the danger of settled communities exploiting their power and status to grow products that would have been beyond the capabilities of ordinary households in the neighborhood.

In the Pachomian community, cows were kept so that milk could be obtained to make cheese, and a few pigs were reared to provide meat for the sick and aged. As in later monastic orders, the consumption of red meat by the fit and healthy was prohibited. The principal food production system was therefore crop farming, complemented by some grazing to produce dairy products and wool.

Monastery gardens sometimes included ponds stocked with fish, which were permitted in place of meat even in stricter communities. During the fourteenth century, dietary rules came to be interpreted with more latitude, leading to a rise in meat consumption and production. Indeed by this time, many monasteries possessed considerable wealth and owned ample estates, which allowed them to grow and sell large quantities of food.

planting, protecting, and harvesting

Throughout the medieval era and later, growing food was a precarious enterprise, as bad weather or disease threatened crops. This was especially true for individual households, who depended on their own small harvests for survival, but lacked the knowledge and infrastructure of the monasteries. Crops required supernatural protection, so people looked for a supernatural solution in the body of Christ, contained in the Eucharistic host, a thin wafer.

Hosts could be removed from churches without clergy knowing, even if the priest placed them directly into communicants’ mouths. A popular account describes a woman taking the host home to sprinkle on her vegetable plot to stop caterpillar damage. In England the host was sometimes deployed to ensure seed germination or to scare off birds. When buried in a field, it was thought to ensure a good harvest.

In France it was carried around vineyards in a procession to safeguard the vines and assure a good vintage. In Germany processions through fields were thought to prevent flooding, pests, and storms, which would have imperiled both crops and animals.

People put strong pressure on clergy to cooperate in these processions, and clergy usually did so for fear of being blamed for a poor harvest. Furthermore many stories were told of the host protecting animals. It might be placed in a hive to preserve its bees or installed in a shepherd’s staff to safeguard the flock.

Medieval farm workers were also attuned to the paradox of the agricultural cycle, which brings life and nourishment, but requires a double death, at planting and at harvest. The sowing of seed was likened to the burial of Christ’s body in the earth, encouraged by Christ’s presentation of himself as a grain of wheat that falls into the ground and dies (John 12:24). Harvesting was recognized as an inherently violent activity. This is well illustrated in the centuries-old British folk ballad, “John Barleycorn,” which describes the cutting and binding of grain sheaves for ale-making in terms reminiscent of Christ’s Passion and Crucifixion:

With hooks and sickles keen,

Unto the fields they hied,

They cut his legs off by the knees,

And made him wounds full wide.

Thus bloodily they cut him down,

From place where he did stand,

And like a thief for treachery,

They bound him in a band.

Metal tools, which evoke scourges, appear in the cutting down of the wheat. Farm workers thereby recollected, and even re-created, Christ’s Passion. By together enacting the Passion, the workers acknowledged their own contribution, as fallen humans, to the world’s sin and to its rejection of Christ. Yet when the time came to feast on the fruits of their labor, they were equally able to celebrate, also in community, the abundance of God’s gifts to them.

green sisters

During the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, community farming continued as people tried to reconnect with the land and thereby with each other. William Booth, who founded the Salvation Army, had just such a vision to connect food with ministry. In his blueprint Farm Colony at Brickfields in England, he housed unemployed and homeless people and trained them to grow fruits and vegetables, as well as to raise pigs, poultry, and rabbits.

Today many other Christian groups have built their identities around organic, seasonal, and sustainable agriculture. For instance across North America, dozens of communities of Roman Catholic nuns grow much of their own food, enjoying high-quality and simple produce. This includes unusual varieties not to be found in grocery stores.

Dubbed “Green Sisters” by Sarah McFarland Taylor, some of these nuns embrace food growing as a spiritual discipline and a devotional practice, spreading their message through the “Sisters of Earth” network.

In rundown urban areas where affordable, healthy food is often difficult to obtain, churches have been instrumental in setting up community gardens. An example of asset-based community development (ABCD), such gardens provide more than food for people in the locality.

Much like ancient monastic gardens, these gardens also place local residents at the center of the planning, growing, harvesting, and distribution of crops. They reconfigure urban geography, creating new meeting places and pointing to new ways of organizing communities. They also revive many churches by helping them build new connections with their neighbors around an activity fundamental to human flourishing.

While we no longer live in Eden, we still have glimpses of God’s garden. CH

By David Grumett

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #125 in 2018]

David Grumett is senior lecturer in theology and ethics at the University of Edinburgh, the author of Theology on the Menu, and the editor of Eating and Believing.Next articles

The royal way

Feasting or fasting? the constant Christian tension in the public square

Kathleen MulhernFasting: from the Orthodox front lines

we should consider the spiritual discipline of not eating

Frederica Mathewes-Green