Seeking renewal

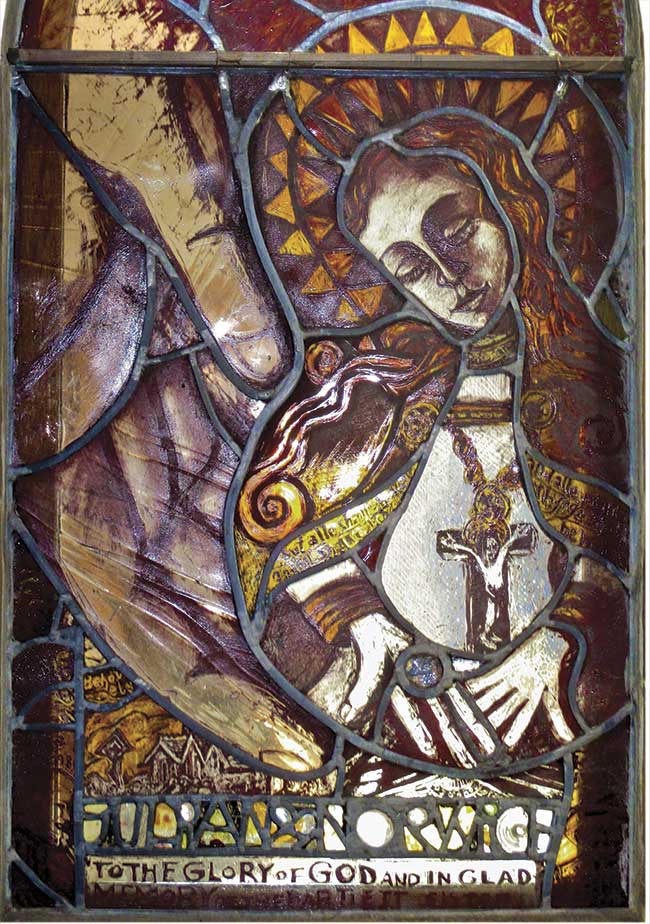

[The second north aisle window of St Augustine’s Church, Scaynes Hill, West Sussex. It was produced by Rosalind Grimshaw in 2002, and depicts Julian of Norwich—Antiquary / [GNU 1.2] Wikimedia]

This year, for the first time, I was planning to attend the Evangelical Press Association’s Annual Conference. Not only was I looking forward to meeting other writers and engaging with the publishing professionals, but the trip was going to serve double duty. My wife has never been to Colorado—and I haven’t been there since I rode through as a child—so it would have been a real treat to visit that beautiful state.

And then a disconcerting coronavirus became the monster in the news.

We waited as long as we could to decide whether or not to make travel arrangements, but in the end, the decision was made for us: the conference was canceled. Needless to say we were disappointed to lose this opportunity. But on reflection, our loss is dwarfed into insignificance compared to the losses some are now enduring, and it reminds me of how Christians of the past experienced and responded to plagues.

Visions from a brush with death

When Julian of Norwich (see p. 21) was about eight years old in the fourteenth century, plague carried off almost everyone of importance in her immediate circle. The experience made her spiritually attuned and unusually conscious of death. She soon prayed to experience as close a brush with death as one can have and still survive. Perhaps her famous visions would never have happened without that childhood experience and her earnest prayer.

The results of her experience were unique, but prolonged exposure to death all around was not. During the Middle Ages, about one-third of all Europeans died of the Black Plague (see p. 17–19). Suffering loss, terrified flagellants gathered for large processions, carrying crosses and whipping themselves as public acts of penance. The church frowned on these acts, but desperate people saw the hand of God in their troubles and ignored religious authorities as they sought relief.

Sometimes plague reset the world order. The Hussites of Bohemia (followers of noted Bohemian reformer Jan Hus) lost their greatest general when Jan Žižka (c. 1360–1424) died of bubonic plague. After many victories against great armies, his name had become sufficient to strike terror in his enemies. That terror was never again evident, and in time, the Hussites lost all that they had gained.

In other cases such societal upset had a domino effect. When an epidemic came to Wittenberg, Germany, in 1552, the university moved temporarily to Torgau. Because feeding and housing students was her livelihood, Martin Luther’s impoverished widow, Katharina (1499–1552), decided to follow them. Near the gates of Torgau, her horses bolted, forcing her to leap into a lake. Severely injured, Katharina never recovered and died later that year. Her reported last words were “I will stick to Christ as a burr to cloth.”

A few years earlier, epidemic had brought embarrassment to the Reformed clergy of Geneva. After one of their number died from disease acquired while visiting the sick in 1543, the rest (including John Calvin) refused to attend the dying. Calvin said, “It would not do to weaken the whole Church in order to help a part of it,” and the other clergy declared that God had not given them the courage to undertake the task. [As a reader pointed out, the quote was not fair to Calvin. He was weighing options in a letter to Viret when he said this.]

Sebastian Castiello (1515–1563) alone was willing to make the visits, and city authorities prepared to enroll him among the clergy. But Calvin barred the appointment on two doctrinal grounds, and Castiello left Geneva, sometimes having to beg for provisions.

Yet sometimes plague has brought unexpected hope on its wings. Clergyman John Harvard (1607–1638) inherited wealth when relatives died during an epidemic. He moved to New England where he soon succumbed to tuberculosis, but not before willing half his estate and all of his books to support a recently established college in New Towne (today Cambridge), Massachusetts. In honor of its benefactor, the school changed its name to Harvard College—today’s Harvard University.

As God has gifted each of us

No one yet knows what lasting impact the current pandemic will leave or how history will record our response. Whatever the personal, national, or international shakeout, the lesson of church history is that those who remain must move forward. How should we do so? As God has gifted each of us.

For some it will be in mysticism. For others in grief. Still others may find duty requires them to brave danger. Others may find themselves with inheritances they can use for God’s work. For now, secure in our sovereign God, we can all fall to our knees in prayer, asking that no matter how the current pestilence develops, the world might experience a renewal of repentance and faith.

CH

By Dan Graves

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #135 in 2020]

Dan Graves is layout editor at Christian History. This article originally appeared as a blog post on our website.Next articles

Demonstrating the love of Christ

At the very beginning of the church, Christians were known for their compassion in times of illness

Gary B. Ferngren“We learn not to fear death”

The plague of 250 roused the Christians of Carthage to action under the leadership of their bishop Cyprian.

Cyprian of CarthageWhen a third of the world died

During the catastrophic Black Plague, how did Christians respond?

Mark Galli