"Something profound had touched my mind and heart”

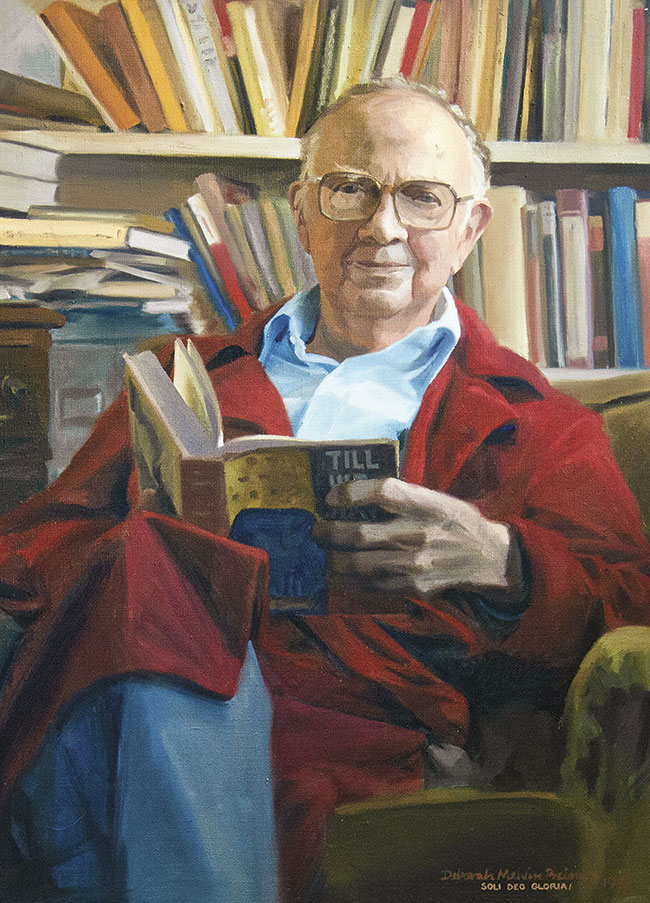

[Above: Deborah Melvin Beisner, Portrait of Dr. Clyde Kilby, 1987, Wheaton College, Oil on Canvas—Used by permission]

Lewis’s more academic friends and colleagues often loom large in works about him; while we’ve devoted this issue to featuring others, we didn’t want to forget them. In addition we introduce you here to two of many scholars who have helped promote Lewis’s work.

CHARLES WILLIAMS

(September 20, 1886–May 15, 1945)

C. S. Lewis read and loved Charles Williams’s novel Place of the Lion in 1936 and wrote a letter to the author:

I never know about writing to an author. If you are older than I, I don’t want to seem impertinent; if you are younger, I don’t want to seem patronizing, but I feel I must risk it.

Just as Williams received the letter, he was writing Lewis after reading his The Allegory of Love. A deep friendship began.

Charles Williams (photo, next page) was born in London and attended St. Albans School, after which he went to University College London. Unable to pay the tuition there, Williams left the university and began work as a proofreading assistant at Oxford University Press, eventually climbing the ranks to editor. In addition to his successful editing career, Williams was also a wide-ranging author of novels, poetry, literary criticism, theology, drama, and history.

When Oxford University Press moved its offices from London to Oxford at the start of World War II, Williams became a regular at Inklings meetings. He was there to hear early drafts of Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings, and the Inklings helped workshop Williams’s final novel, All Hallows’ Eve.

Lewis was fascinated by Williams’s theological assumption that experiencing romantic love helped people better relate to and love God:

While writing about Courtly Love I have been so long a student of your province that I think, in a humble way, I am nearly naturalised.

Oxford scholar Nevill Coghill, who introduced Williams’s work to Lewis, recalled that Williams and Lewis “quickly became fast friends: they seemed to live in the same spiritual world.” Their intellectual and spiritual friendship continued until Williams’s passing in 1945 as a result of an emergency operation a few short months before the end of World War II.

J. R. R. TOLKIEN

(January 3, 1892–September 2, 1973)

Born in 1892 in what today is South Africa, John Ronald Reuel Tolkien moved to England with his mother and brother at the age of three after his father died of rheumatic fever. He was raised in a village near Birmingham. Tolkien’s mother died when he was 12, leaving him and his brother under the care of Father Francis Xavier Morgan, about whom Tolkien later recalled, “I first learned charity and forgiveness from him.” He graduated from Exeter College, Oxford, in 1915, married Edith Bratt in 1916, and went on to fight in World War I.

By 1926 Tolkien was a professor of Anglo-Saxon at Oxford, where he met Lewis. They soon became friends, largely based on their mutual love of language, myth, and literature—and also, perhaps, because of their similar pasts: losing parents when young and fighting in World War I. Tolkien and Lewis shared their literary works with one another, often as part of Inklings meetings. Tolkien later said that Lewis “was for long my only audience.”

When they first met, while Tolkien was devoted to his Roman Catholic faith, Lewis was an avowed atheist. But on September 20, 1931, in the early morning, Lewis, Tolkien, and fellow professor Hugo Dyson walked on the grounds of Magdalen College. Lewis later wrote:

Now what Dyson and Tolkien showed me was this: that if I met the idea of sacrifice in a Pagan story . . . I liked it very much and was mysteriously moved by it . . . provided I met it anywhere except in the Gospels. . . . Now [I see] the story of Christ is simply a true myth: a myth working on us in the same way as the others, but with this tremendous difference that it really happened.

Tolkien and Lewis used their mutual love for literary myth and legend—as well as their academic understanding that for generations people had used myths to articulate existential realities—to create their own worlds, most famously Narnia and Middle-earth. Their 40-year friendship spanned literature, creativity, critique, and life-changing faith.

DOROTHY L. SAYERS

(June 13, 1893–December 17, 1957)

Dorothy L. Sayers and C. S. Lewis began their friendship through letters, and they found in one another intellectual equals and joyful sparring partners. Lewis considered Sayers his first fan “of importance” and called her “a high wind” for her ability to debate and her knowledge of both literature and theology.

Sayers (whom we also met in CH issue #139) was born in Oxford, the daughter of a clergyman, and won a scholarship to Somerville College, Oxford. She graduated in 1915 with First-Class Honours in modern languages and medieval literature.

Following her time at Oxford, Sayers wrote poetry and worked as a teacher and advertisement copywriter. In the early 1920s, she began work on her first of 12 Lord Peter Wimsey detective novels, popular in both the United Kingdom and the United States.

Sayers was most proud of her translation of Dante’s Divine Comedy, “a great Christian allegory,” and she also became famous for her apologetic works, including The Mind of the Maker (1941), Creed or Chaos? (1947), and her play cycle on the life of Christ, The Man Born to Be King (1943).

Though Lewis was a somewhat more willing apologist than Sayers, they were able to walk together as Christian advocates in a world often antagonistic to their work (even Tolkien was not a huge fan of Lewis’s apologetics). When Sayers believed her apologetics work was taking her away from her other literary interests, Lewis encouraged her to continue, believing her to be talented and her work invaluable.

In 1943 Lewis read Sayers’s 12-part play cycle and wrote to her,

I’ve finished The Man Born to Be King and think it a complete success. . . . I shed real tears (hot ones) in places. . . . I expect to read it times without number again.

Indeed he read it every Holy Week thereafter. Their friendship, marked by support and friendly debate, continued until her death in 1957.

OWEN BARFIELD

(November 9, 1898–December 14, 1997)

Though Owen Barfield was by nature introverted, J. R. R. Tolkien once called him “the only man who can tackle C. S. L.” in an intellectual tussle. Born 20 days before Lewis in 1898, Owen Barfield first met his friend when they were students at Oxford.

Barfield pursued a literary career following graduation from Wadham College in 1923, but fearing he would be unable to fully support his family, he joined his father’s law firm and practiced law in London, retiring in 1959.

Both during his law career and after, Barfield published many books, including his philosophical magnum opus, Saving the Appearances: A Study in Idolatry (1957).

Throughout their twenties, Barfield and Lewis fought a philosophical “Great War”—in-depth discussions of mythology, atheism, and religion—which concluded when Lewis moved toward the theism Barfield already professed.

In Surprised by Joy, Lewis described himself as a fox (atheist) in a field being chased by hounds (theists):

And nearly everyone was now (one way or another) in the pack; Plato, Dante, MacDonald, Herbert, Barfield, Tolkien, Dyson, Joy itself. . . . Enough had been thought, and said, and felt, and imagined. It was about time that something be done.

Lewis became a theist in 1929 and a Christian two years later.

Lewis and Barfield continued their close friendship until Lewis’s death in 1963; Barfield would sometimes journey to Oxford to take part in Inklings meetings. He once said of Lewis,

Now, whatever he was—and as you know, he was a great many things—C. S. Lewis was for me, first and foremost, the absolutely unforgettable friend, the friend with whom I was in close touch for over forty years, the friend you might come to regard hardly as another human being, but almost as a part of the furniture of my existence.

CLYDE S. KILBY (September 26, 1902–October 18, 1986)

Born the youngest of eight children in the hill country of Tennessee, Clyde Kilby was the first in his family to attend college. Following his graduation from the University of Arkansas, he received his master’s degree from the University of Minnesota before moving on to teach English at Wheaton College. He earned his PhD through correspondence courses at New York University.

Kilby first read C. S. Lewis’s The Case for Christianity (later the first part of Mere Christianity) in 1943. Taken in by Lewis’s words, Kilby read all of his work and immediately went to design a course for students on both Lewis’s and Tolkien’s mythical-Christian writings.

Kilby also began a years-long correspondence with Lewis, culminating in a collection of letters he later housed at the Marion E. Wade Center, which he created in 1965 as the “C. S. Lewis Collection,” at Wheaton College (we were introduced to the Wade Center briefly in CH issue #139 as well).

In addition to Lewis’s letters, the Wade Center went on to collect papers, letters, books, and manuscripts of six other British authors affiliated with Lewis either through fandom or friendship: Owen Barfield, G. K. Chesterton, George MacDonald, Dorothy L. Sayers, J. R. R. Tolkien, and Charles Williams.

In the 20 years that Kilby knew Lewis (from the first time he read The Case for Christianity until Lewis’s death in 1963), Kilby saw the importance of Lewis’s apologetic work and dedicated his career to collecting and cataloging the author’s words at the Wade Center. Recalling his first moments reading Lewis, he once said,

I bought the book and read it right through feeling almost from the first sentence that something profound had touched my mind and heart.

WALTER HOOPER

(March 27, 1931–December 7, 2020)

Born in North Carolina, Walter Hooper studied English at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. At a campus ministry meeting, a football player described the story of The Screwtape Letters—a senior demon instructing a junior demon how to tempt humans—leaving Hooper enthralled. Unable to find any Lewis books in the university bookstore, he did find an introduction C. S. Lewis wrote to a translation of the Epistles: “I’d never met anybody who believed that way. I was determined to have more words by this man.”

Following service in the Korean War, Hooper taught English at the University of Kentucky, while working on a book about Lewis. Hooper was able to visit Lewis in England in 1963, where they had three pots of tea followed by a pint with the Inklings. Hooper later recalled, “As he and I walked on towards the pub where I would get the bus back, I didn’t know whether I’d ever see him again. But I thought, I really love this man.”

Hooper served as Lewis’s private secretary in his last months of life, and, following Lewis’s death (and, eventually, Warnie Lewis’s death in 1973), he managed the author’s literary estate. He moved to England and made it his life’s work to promote Lewis’s works and keep them in print.

In addition to editing and collecting a number of Lewis’s unfinished works—including The Dark Tower (1977), The World’s Last Night (1960), and Selected Literary Essays (1969)—Hooper also wrote his own Lewis companion, the 940-page C. S. Lewis: A Companion and Guide (1996). A Christianity Today review notes:

This readable volume seems to reflect a lifetime of meditating on everything written by Lewis and about him, of talking to those who knew Lewis, and of ruminating upon his own conversations with Lewis during their brief acquaintance.

Having served as a deacon and priest in the Church of England, Hooper converted to Roman Catholicism in 1988, something he believed Lewis would have eventually done (Hooper said, “Anglicanism seemed a mess”). He died of COVID-19 in 2020. CH

By Jennifer A. Boardman

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #140 in 2021]

Jennifer A. Boardman is a freelance writer and editor. She holds a master of theological studies from Bethel Seminary with a concentration in Christian history.Next articles

City of Man: Did you know?

What is civic engagement? Church leaders have long reflected on how Christians should live in the world

The editors