Start seeing persecution

HAVE YOU SEEN the bumper stickers that say “Start seeing motorcycles”? Those working on the frontlines of global Christianity are trying to get the rest of us to start seeing the persecution they see every day and to stand alongside those who are suffering for their Christian faith. Roy Stults, educational services coordinator and administrator of The Voice of the Martyrs’ online classroom, shares with Christian History some things he has learned researching and teaching about the persecution of Christians.

CH: What are we not seeing when we don’t see persecution?

RS: Many Christians in the West either deny or are ignorant of it, but persecution is part of present reality. It has many forms—political oppression, ethnic hatred, religious prejudice, and outright hatred of Christians.

Many value the fight to combat social persecution, such as human rights issues and human trafficking. Fighting for human rights is very significant work; but religious persecution is not a popular subject. Since Western churches seem to be experiencing little if any persecution, people see the issue as too negative to fit with the “good news” of the gospel. People also fear that if Christians expose and combat persecution too vigorously, it might jeopardize interreligious dialogue.

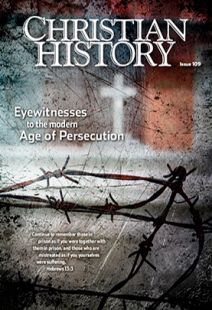

But the Bible reminds us, “Continue to remember those in prison as if you were together with them in prison, and those who are mistreated as if you yourselves were suffering” (Heb. 13:3). How can we shine a light on deeds done in utmost darkness and behind walls of secrecy?

Here are some examples. In Nigeria the radical group Boko Haram bombs a church and dozens are killed and injured. Church burnings and bombings there continue to kill hundreds of Christians even today. In Colombia militants kill a pastor when he refuses to close his church despite threats. Other pastors receive similar threats. In Iran the courts condemn Christians to death or years of imprisonment on charges of apostasy. Churches are raided and congregations arrested; pastors are randomly held and released.

In Algeria the government requires churches to register but denies registration when they try to comply. In China persecutors bulldoze a church in Shouwang and arrest legitimately licensed bookstore owners and managers.

In India extremists incite racial and religious hatred, disrupting Christian prayer meetings and beating believers. They accuse Christians of forcing people to convert, of disturbing the peace, and of insulting Hindu deities. Local authorities in one Mexican town hold and torture four evangelical Christians for three days, until state authorities rescue them.

Universities and industries deny Christians in various countries access to higher education and employment because of their faith. Christian leaders receive threatening phone calls and intrusive surveillance. Officials arbitrarily arrest and imprison civil rights lawyers on trumped-up charges.

CH: How would you define persecution?

RS: One evangelical theology of persecution, the Bad Urach Statement of the International Institute for Religious Freedom, says persecution is any “unjust hostile action which causes damage from the perspective of the victim.” It can come from multiple motivations and take multiple forms and degrees.

We call an unjust action against a believer or a group of believers motivated by religious reasons “religious persecution.” Other motivations, such as ethnic hatred, gender bias, or political ideologies, may also contribute.

Glenn Penner, author of In the Shadow of the Cross, a biblical theology of persecution, calls persecution against Christians “a situation where Christians are repetitively, persistently and systematically inflicted with grave and serious suffering or harm.” Also Christians may be deprived of basic human rights—or threatened with this—because of “a difference that comes from being a Christian that the persecutor will not tolerate.”

Some writers distinguish between census, member, practicing, and committed Christians. The census Christian, at one end of the scale, is Christian in name only. The committed Christian, at the other end, has a life centered on his or her faith. All four groups can experience persecution, however. A persecuted Christian is anyone persecuted because of faith in, or association with, Christ.

CH: Why do people overlook the reality of persecution?

RS: Many deny it because they may not personally experience it. Eric Metaxas, author of Bonhoeffer, says that “those of us who live in the modern West don’t experience anything along these lines, and most of us are deeply ignorant of the sufferings of our brethren around the world. Indeed, as we read these words now, millions suffer.”

The Bad Urach Statement makes a similarly strong indictment against the Western church, accusing it of “apathy, lack of empathy, and cowardice . . . because such reports disturb the idealistic pictures of harmonious life elsewhere, and might endanger ecumenical and inter-religious relations.”

By not seeing persecution, we fail to see our opportunity to stand alongside those who are suffering and to use the opportunity to prepare ourselves for potential persecution. When we see other sorts of suffering, like human trafficking, we address it. Why not this one?

The enormity of the issue, the gruesomeness of some persecution events, and our natural inclination to turn away from difficult situations all keep Christians in the West from fully embracing the reality of persecution and fully seeing how they themselves might be experiencing it. According to the Bible, persecution will not cease in this life but will continue until Christ’s return (Matt. 24:9–14).

CH: What forms does persecution take?

RS:The International Religious Freedom Act was passed by the United States Congress in 1998. In it Congress announced—we might wonder what took them so long!—that severe and violent acts of religious persecution exist: detention, torture, beatings, forced marriage, rape, imprisonment, enslavement, mass resettlement, and death. All occur because of a person’s faith or decision to change his or her faith.

To that list we may also add death threats, assassination attempts, economic suppression, extortion, prohibition from enrolling in institutions of higher education, kidnapping, and being forced to live in substandard housing. Less violent but psychologically devastating forms of persecution include slander, mockery, insults, exclusion from community social events, ridicule, harassment, threat of lawsuit, loss of jobs, and the seizure of property.

CH: How does persecution happen and progress?

RS: I’m drawing here on a 2001 report to the United Nations by the Religious Liberty Commission of the World Evangelical Fellowship. It presents three categories: disinformation (intentionally spreading false information), discrimination, and persecution.

These categories represent a “slippery slope.” Each has an active and a passive aspect: actively, the state uses its own agencies to promote an agenda against Christians; passively, the government allows private agencies or groups to denounce Christians.

That pattern of persecution is a logical progression, but it may not be an actual progression. Persecution does not necessarily move from low intensity to higher intensity: a variety of kinds and intensities of persecution may occur at one time or from time to time.

Sometimes because of social pressure against the persecutors, persecution may “downshift” from violent attacks to slanderous propaganda. Increased levels of persecution may depend on the level of resistance believers offer. Or as often happens, authorities may resort to ever-increasing intensities if they are unsuccessful at coercing Christians at a lower level—this was Wang Mingdao’s situation (see “Stubborn saint,” pp. 21–24). And as Christians we must not rule out the influence of spiritual darkness that motivates and fuels persecution.

I think each category and aspect of persecution is persecution. Disinformation may begin a process that leads to “persecution,” but it can be called persecution as well. That kind of persecution is found in Western countries as well as in the majority world.

CH: Why do people or governments persecute?

RS: Generally speaking, persecution happens where Christians are seen as a threat to one of three social realities: prevailing religious beliefs (especially where religious belief equals cultural, political, or ethnic identity); social stability (breaking up family and community unity); or political allegiances (where religion and state are closely identified or identical).

In many nations religious beliefs are strongly tied to cultural, political, and ethnic identity. To call yourself a Pakistani, for example, is seen as saying, “I am a Muslim.” To self-identify as Christian marks the believer as a target. Since by definition a Christian cannot also be a Muslim, then, the logic goes, they cannot be a true Pakistani.

The more militant groups within a religion frequently target Christians because of these groups’ attitudes toward religious outsiders and the belief that Christians blaspheme their gods and religious leaders. Asia Bibi’s persecutors were upset that she drank from the same water glass as they did and accused her of blaspheming the prophet Muhammad (see “Imprisoned over a glass of water,” pp. 38–40).

Tribalism is sometimes at fault too. This radical form of the belief that one’s own culture is superior to all others sees the tribe as the most important allegiance in life. Loyalty to another god destroys social cohesiveness. In many cases the tribe sees Christianity as a Western religion threatening their traditional social fabric.

Governments become persecutors when allegiance to the government clashes with Christians’ ultimate allegiance to Christ—especially when the state seeks to be the ultimate authority and demands total allegiance, such as under Communism. Communist countries have also persecuted Jews for that reason—the fact that their ultimate loyalty lies with God and not the state.

Many governments apply pressure hoping to stamp out Christianity altogether. Some Western countries allow religious freedom but impose laws that render religion ineffective in influencing public life, morals, or policy.

The attempt to keep Christianity from being fully Christian—as when the name of Christ cannot be mentioned in public prayer—functions as a subtle form of harassment and discrimination. This harassment relegates Christianity to private life and keeps Christian influence from the public forum, in hope that it will merely fade away.

CH: How are Christians under persecution to understand their suffering?

RS: Christians experiencing persecution typically interpret this suffering as being for Christ’s sake while in his service. We see this in testimonies from the first century to the twenty-first: from Perpetua—“I realized that it was not with wild animals that I would fight but with the Devil, but I knew that I would win the victory,” to Edith Stein—“One cannot desire freedom from the Cross when one is especially chosen for the Cross.”

Richard Wurmbrand, who suffered for his faith in a Romanian jail, wrote: “God says we should serve Him not only with all our heart, but also with all our mind. This means intellectual work, hard work” (see “Tortured for Christ,” pp. 10–12). He also said that preparation for underground work begins by studying “sufferology.”

A theology of persecution and suffering for Christ’s sake is not a luxury. Through “sufferology” Christians grasp God’s will in persecution and suffering. A theological framework helps us to recognize, understand, and evaluate persecution. It’s a part of acquiring a mature perspective based on rational understanding, rather than just relying on our emotions to determine our response.

CH: How do we do this biblically and theologically?

RS: First, what does the Bible teach about persecution and suffering for righteousness’ sake? Since much of the New Testament is written to Christians in the midst of persecution, should we have a “persecution hermeneutic” to correctly determine the meaning of certain passages?

Second, how central is persecution to the whole of biblical teachings, or is suffering for righteousness’ sake only a minor theme?

Then, how do persecution and suffering factor into God’s purpose and method for reaching the world?

Finally, does suffering count for something beyond just being a witness? Is there some redemptive value to suffering?

It seems that suffering for righteousness’ sake is the method God uses to reach, redeem, and transform the world. We can expect persecution and suffering (John 15:18–20 and 2 Tim. 3:12). In many contexts a public witness for Christ leads to persecution and suffering. The suffering of God’s witnesses makes a sacred offering to God, who honors the witness and releases grace in redemptive ways into the situation. It is also a blessing to those who are persecuted (Matt. 5:10–11; Phil. 1:29).

This suffering does not redeem in the same way that Christ’s sacrifice did, because Christ’s death atoned for us once and for all time. But the suffering of his witnesses participates in some manner in his sufferings. It extends that sacrifice (Col. 1:24), and it continues the ministry of Christ that began with his death on the cross for our sins (Phil. 3:10).

When we witness under suffering, it applies the grace that was generated at the atonement for both the witness and the persecutor. The suffering of the witness can be the avenue of saving grace for the persecutor—as with Isaac Jogues, whose willingness to die led one observer of his death to convert to Christianity (see “Did you know?,” inside front cover). For this reason we pray for persecutors.

Finally, the grace that comes from the atonement of Christ through the Holy Spirit counteracts evil, transforms people and situations, transfers people from the kingdom of darkness to the kingdom of light, frustrates Satan’s attempt to establish dominion, brings the spiritually dead to life, and saves people from their sins.

Our present sufferings for Christ’s sake will be rewarded by sharing in his glory. There is no comparison between the present persecution and the glory that will come (Rom. 8:16–18)! CH

By The editors and Roy Stults

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #109 in 2014]

Roy Stults is educational services coordinator and administrator of The Voice of the Martyrs’ online classroom.Next articles

Tortured for Christ

Richard Wurmbrand stood for Christ behind the Iron Curtain. It cost him 14 years in prison

Merv KnightMarching in the Lord’s Army

A Romanian Orthodox renewal group faced persecution from both church and state

Edwin Woodruff TaitOffering himself for a stranger

Maximilian Kolbe gave his life to save another prisoner from the Nazis

Heidi Schlumpf