The “Church of the Horse”

IT WASN'T ILLICIT SEX that did Jeremiah Minter in, or financial misconduct, or any of the other sins that cause the downfall of leaders today. And it wasn’t over-the-top emotional intensity or extravagant piety, as early Methodists typically accepted and even encouraged these things. But in 1791 Jeremiah Minter crossed a line that even the Methodists could not accept.

What was the offense that cost Minter not only his position of leadership but also his Methodist membership? Minter had been voluntarily castrated in an attempt to obey the words of Jesus found in Matthew 19:12—“live like a eunuch for the sake of the kingdom.” His expulsion from the church was not the end of the saga.

Upset with Methodist bishops Francis Asbury and Thomas Coke because of his expulsion, Minter published an exposé claiming the two bishops were actually sorcerers. Minter even swore that he personally had seen these pious leaders of the church practice magic.

Still, Minter was not some madman at the far fringes of early American Methodism. He had been an active itinerant preacher and continued to preach independently even after being cast out. He went on to publish his own hymnal with selections similar to those in hymnals compiled by preachers who stayed within the Methodist movement. And he remained close friends with famous early Methodist Sarah Anderson Jones, a married woman in southern Virginia known widely for her intense piety and popular hymns with a mystical tone.

Jones, despite these fervent hymns, was no outlier, either, but a woman so respected that Asbury preached her memorial service. Jeremiah Minter may have been a little too intense, but the Methodism surrounding him was not exactly quiet and sedate.

Both ecstatic and solemn

What was it like to be an early Methodist? It was a highly disciplined way of being a Christian. Indeed, members lived in some ways according to a monastic discipline even while marrying and living in regular households rather than in monasteries.

Methodist organization encouraged this. Methodists in a given locale were organized into groups called societies, not into traditional congregations or parishes. Many societies would then be grouped together into a charge. Traveling preachers were assigned to a given charge by the bishop. A charge based in a city was known as a station, while one that expanded into the countryside was called a circuit.

Whether in the city or the country, all societies lived by clear rules of life called the General Rules of the United Societies, which provided the framework of expectations. In addition widespread standards for behavior grew out of the concise statements of the General Rules and could go beyond them. Chief among these widely accepted standards were commitments to keep Sunday as a strict Sabbath, dress simply, and avoid secular entertainments—drinking, dancing, and other pursuits commonly engaged in by the culture of upper-class gentility.

Methodists did not allow their fellow members to pursue this way of life individually. They possessed multiple mechanisms for accountability. New members underwent an initial six-month probation. If received into full membership after that time, a new Methodist was given a membership ticket that needed to be renewed quarterly.

The chief traveling preacher of a society conducted individual interviews to assess faithfulness and growth in grace. Members needed a current ticket to be admitted to certain in-house worship services like the love feast (a sharing of bread, water, and testimonies). This heavy hammer of accountability was a trial to many rank-and-file members—as well as to some preachers, as in the case of Jeremiah Minter.

Beyond these denomination-wide standards for behavior, Methodists enforced even more behavioral standards in local contexts. Quarterly Meeting Conferences were the four-times-a-year administrative meetings for Methodists organized into a charge. There they did their best to discipline errant members. Sometimes these conferences passed local legislation; one quarterly meeting prohibited letting horses out for stud on the Sabbath.

Other conferences dealt with helping members with their finances so their debts would not bring shame on the whole. One Maryland circuit required member Robert Shanklin to turn over part of his wages to help him figure out a way to pay his debts. Perhaps the most poignant examples—mainly found in the mid-Atlantic states—were decisions by conferences on how long a Methodist could own a newly purchased slave before emancipating him or her.

All these disciplinary measures had an ethical goal (to become a holy and distinctive people) and an ethical tone (being committed to Jesus). William Spencer expressed this core Methodist aspiration in 1790:

Solemnity is the very life of religion. O, Lord Jesus, make me more and more solemn every day. Death is solemn. Judgment is solemn. God is solemn. Christ is solemn. Angels are solemn. O! how can I be trifling? May God Almighty make me solemn and deeply pious and faithful for the Lord Jesus’ sake.

Being a holy people

In its organization, Methodism was also unique among American denominations. Early Methodists would not have known or expected a pastor in residence overseeing a single congregation. That was what other churches did.

No, instead of preaching in a parish church, watching over a local flock, Methodist ministers rode daily from one stop to the next, preaching their circuits, an itinerary that usually took four weeks. These itinerant preachers traveled the same route month after month, year in and year out, staying with members of their charge along the route.

One day they might preach in a barn, the next in a house, and the next at a crossroads. They could even use the same sermon until they looped back around to begin again. If you live in a section of the country where there seems to be an old Methodist church every 5 to 10 miles, you might be seeing the vestiges of one of these circuits. And think about it: a lazy preacher 200 years ago only needed about a dozen sermons a year, one for each month around the circuit. (But Methodist preachers typically were not lazy!)

Usually two itinerants, spaced two weeks apart, traveled around the circuit, preaching nearly every day for four weeks. That meant that Methodists in any one locale might have their preaching service, the mainstay of Methodist worship, once every other week on possibly any day of the week. The itinerants considered it critical to make it to these appointments to preach. To this day Methodist preachers are still “appointed” to a particular church or churches by their overseeing bishop.

Round and round and round

Supplementing the work of the itinerants, Methodism employed men called local preachers. These men did not travel, were not paid to preach, usually did not preach as well as the itinerants, and could not administer the sacraments. There seem to have been about three local preachers for every itinerant on a circuit. They preached on many days and occasions when the itinerant could not be in attendance.

In addition to local preachers, licensed exhorters spoke after the sermon, exhorting the congregation to respond appropriately in both their emotions and their actions. (Women, though they could not be preachers, sometimes served in the exhorter’s role.) A Methodist preaching service could be a very crowded affair if multiple preachers and exhorters were present: usually everyone was given a chance to speak, one after another, in rapid succession.

Preachers in cities also circulated among various congregations, preaching three services each Sunday (morning, afternoon, and evening). This meant that a Methodist city worshiper heard a different preacher at every service. The rotation and frequency of services were possible because all the city preachers lived relatively close by. But even then, everything kept rotating, rotating, rotating.

That sense of constant traveling even applied to the ministers who had supervisory roles. Put several circuits or stations together and one had a district, supervised by a presiding elder who constantly traveled across it.

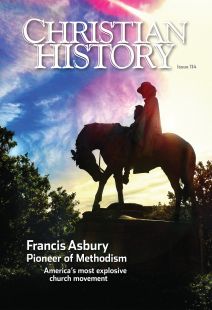

Several districts joined together formed a conference, which met annually and was supervised by a bishop, like Asbury, who made it a point to regularly visit the many circuits under his supervision (and take notes on all the preachers). These bishops, too, seemed to be perpetually in the saddle. Perhaps Methodism should have been called the “Church of the Horse.”

Every quarter the presiding elder met with the itinerant and local preachers and with other leaders within a circuit or station. The administrative details took only a little time; Methodists dedicated most of these quarterly meetings to worship and evangelizing. Not surprisingly, Methodists and non-Methodists, leaders and people alike, would gather from across the circuit to attend. In essence, each local group of Methodists typically lived in self-imposed ecclesiastical separation from the other Methodists on their circuit, except for the four times each year when they all gathered together.

In the era of the American Revolution, these quarterly meetings became the scene for revivals. Soon someone somewhere suggested that the participants should all bring their own food and provisions for sleeping instead of being assigned to the houses of Methodists who lived in the area. Voila: camp meetings were born.

Challenged by classmates

But Methodist spiritual oversight did not depend entirely on preachers. Indeed, rank-and-file Methodists did not receive most of their pastoral care from preachers. Joining the Methodists meant one was also joining a class that met together each week under the direction of a class leader. These weekly meetings were the backbone of the movement.

In these smaller groups, members practiced an intimate, direct, and specific discipleship—the accountability that was at the heart of the Methodist movement. Here those who lived nearby and knew them challenged, encouraged, and comforted them. Among early Methodists, it was your class leader who really knew you.

Methodism also thrived on a combination of individual devotion and corporate worship. Methodist families were expected to conduct daily family prayer. Like almost all Methodist praying, these domestic prayer services were done extemporaneously. Corporately, Methodists conducted not only their mainstay preaching services, which were open for anyone to attend, but also occasional private services like love feasts and the Lord’s Supper.

The private services were open to Methodists with current membership tickets and others who had been granted permission to attend. Even though they occurred only quarterly, they were the highlight of Methodist worship. Methodists fell over themselves to find the words to express their experiences of God and Christian fellowship on these occasions. Perhaps the loveliest description came from one Methodist who estimated that he and his fellow believers had been dwelling in the “suburbs of heaven.”

The strict discipline and meticulous organization of the Methodists stood in stark contrast to their worship style, which can only be called messy. Some of that messiness was literal: chewing tobacco was so common that pray-ers might kneel in black juice if there were no spittoons. But the ecstatic, enthusiastic quality of early Methodism lent it a spiritually messy nature in its worship as well. The pinnacle of Methodist worship, simultaneously solemn and ecstatic, was when “a shout of a king in the camp” occurred, an image drawing on Numbers 23:21 and 1 Samuel 4:5–6.

Bishop Thomas Coke described such a scene during a service in 1790 Baltimore:

Out of a congregation of two thousand people, I supposed two or three hundred were engaged at the same time in praising God, praying for the conviction and conversion of sinners, or exhorting those there with the utmost vehemence. And hundreds more were engaged in wrestling prayer either for their own conversion or sanctification.

Early Methodists desired to be swept up into such a strong sense of God’s presence, goodness, and grace that they could hardly stand it, whether praying alone or worshiping in a congregation. Methodists loved to shout during such times. While a few American Methodists avoided shouting, most—whether white or African American—let loose when moved. In fact, so intrinsic was shouting that special hymns were written to celebrate it.

A century later, Methodist Fanny Crosby captured this phenomenon:

There’s a shout in the camp for the Lord is here.

Hallelujah! praise His Name.

To the feast of His love we again draw near.

Praise, oh, praise His Name.

Wild and messy

Get Methodist worship going and it could be wild. During such times official licenses and offices mattered little. Racial, gender, and age divides all fell because any Methodist was granted liberty to speak. Thus women and children often were heard exhorting those around them to seek after God.

A variety of exuberant physical demonstrations occurred. People wept, wailed, and flailed as they grappled with the God of the Gospel. Falling and lying in a stupor seemed especially common. Accompanying such vocal and physical messiness was the pulling aside of the veil between this world and the next. Both in and out of worship, Methodists regularly experienced ecstatic visions and dreams, sometimes of the delights of heaven or the terrors of hell.

All of this happened to the music of Charles Wesley and the many later Methodist hymn writers who built on his poetics of piety, both in their singing and in their everyday religious speech. Many were songwriters themselves. Sarah Jones frequently published her pieces, and Tennesseean John Adam Granade was the Chris Tomlin of his day. Something about Methodist piety with its emotional, evocative, and experiential nature sought expression in poetic form.

Their internal conversation had this poetic messiness too. How did one Methodist ask another about her fellow society members? Not “How is your church doing?” but “How does Zion prosper?” When the time came to name new chapels, popular names like Ebenezer, Bethel, and Pisgah served to remind the faithful of a blurred line between this world and the biblical one.

What was it like to be an early Methodist? Overall it was an intense experience. Though no one else took the drastic step that Jeremiah Minter did to show his piety, all Methodists appreciated a desire to yearn for salvation and burn for the Savior, Jesus Christ:

They are despised by Satan’s train,

Because they shout and preach so plain.

I’m bound to march in endless bliss,

And die a shouting Methodist. C H

By Lester Ruth

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #114 in 2015]

Lester Ruth is a research professor of Christian worship at Duke Divinity School and the author of A Little Heaven Below: Worship at Early Methodist Quarterly Meetings and Early Methodist Life and Spirituality.Next articles

Camp meetings: a Methodist invention?

Revival elements people experienced in 1801 had been part of Methodist life for several decades

Lester RuthThe bishop and his mentor

The saintly German leader who influenced and frustrated Asbury

J. Steven O’Malley“My chains fell off”: Richard Allen and Francis Asbury

Jennifer Woodruff TaitChristian History Timeline: Methodists on the move

How Methodism transformed in America from a small immigrant sect to a leading Protestant denomination

the editors