The heavens declare the glory of God

PSALM 19 PROCLAIMS, “The heavens declare the glory of God; the skies proclaim the work of his hands. Day after day they pour forth speech; night after night they display knowledge” (Psalm 19:1–2). Since the beginning of the church, Christians have affirmed this insight and joined together with the creation pictured in Psalm 19 to worship God.

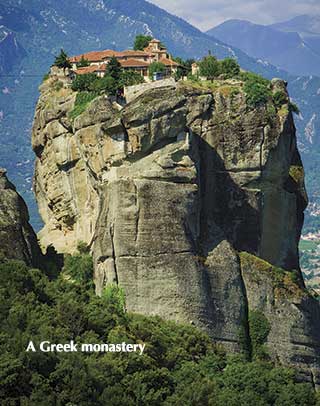

Many of those vibrant believers were monks and nuns who set their lives apart for prayer and memorizing Scripture; but these monastic Christians also tended the garden of creation where the Lord had placed them. Reflecting on God’s attributes displayed in the heavens and on earth, they responded in praise to the Almighty.

Reading the book of nature

Early Christians believed that because the universe was created through the Logos—God’s word, logic, reason, and wisdom—creation reflects God’s order and character. They engaged in, as they described it, “reading” the book of nature. Here they were taking after Jewish thinkers like scholar Philo of Alexandria (c. 25 BC– c. 50 AD) who taught that everyone pursuing wisdom should “contemplate nature and everything found within her” and “attentively explore the earth, the sea, the air, the sky.”

Perhaps the most famous figure of early monasticism, Antony (c. 251–356) meditated deeply on God’s self-revelation in creation. When asked why he had no books with him during his hermitage in the Egyptian desert, Antony responded, “My book is the nature of created things. In it when I choose I can read the words of God.”

Order Christian History #119: The Wonder of Creation in print.

Subscribe now to get future print issues in your mailbox (donation requested but not required).

Basil of Caesarea (c. 330–379), the writer, bishop, and monk who laid the foundation for Eastern monasticism, called on all Christians to read the book of nature: “I want creation to fill you with so much admiration that everywhere, wherever you may be, the least plant may bring to you the clear remembrance of the Creator.”

Basil desired his hearers not simply to enjoy the beauty of nature but to contemplate the biblical lessons reflected in the natural world: “If you see grass, think of human nature, and remember the comparison of the wise Isaiah, ‘all flesh is grass, and all the goodliness thereof is as the flower of the field.’”

Basil’s contemporary and friend Evagrius Ponticus (c. 345–399) communicated this emphasis on creation to Western monasticism. Scripture came first for Evagrius, but he also called his readers to reflect on God’s book of creation, for “in this book are written down also the logoi [principles] … through which we know that God is Creator, wise, provident and Judge.”

Not only does the order of the created world reveal that God exists, Evagrius thought, it discloses God’s very character. He referenced Romans 1:20: “For since the creation of the world, God’s invisible qualities—his eternal power and divine nature—have been clearly seen, being understood from what has been made.” Every part of nature, every created being, bears the structure and principles of God’s wisdom.

Cascading glory

But what does the book of nature teach? We can learn about God through nature, according to many early monastic theologians, because the whole created order is a revelation—a “theophany,” these writers called it—of God’s glory and character. God’s light cascades down from the Godhead, they wrote, to the ranks of angels to the physical world around us to humans, in what became known as the “great chain of being.” Each level discloses divine radiance to the one below it, and all creation welcomes us into worship of the Most High.

Pseudo-Dionysius, a Syrian monk who lived in the late fifth or early sixth century, thoroughly explored this worldview. He asserted,

Every good endowment and every perfect gift is from above, coming down from the Father of lights” [James 1:17]. But there is something more. Inspired by the Father, each procession of the Light spreads itself generously toward us, and … stirs us by lifting us up. It returns us back to the oneness and deifying simplicity of the Father who gathers us in. For, as the Sacred Word says, “from him and to him are all things [Romans 11:36].

Growing in the garden

Monastic writings passed on this lofty theology of creation to later generations, and the monastic lifestyle truly communicated an appreciation of nature. Humble and down-to-earth, this strand of monastic life cultivated gardens and tended fields. Pachomius (c. 292–348), founder of an early monastic community, emphasized humanity’s dependence on creation: “The seasons of fruitfulness, the rains, the dew and the winds destined to make grow the harvests that have been sown in the fields, all things that are necessary to men and to all the creatures have been created by God for man’s needs.”

Desert monks supported themselves—and avoided idle hands and minds—by manual labor. The Rule of Saint Benedict (Benedict lived c. 480–547) codified working with one’s hands; it established a balance of physical labor, individual meditation on Scripture, corporate reading of the Psalms, and prayer. Those are truly monks, asserted Benedict, who work with their hands to bring in the harvest.

In this rhythm of life, manual labor was not simply a tool to provide food for the community, it was an essential spiritual exercise. Tilling the good earth (humis) nurtured humility (humilitas)—a pun in Latin. As monks and nuns worked their gardens, they may have seen parallels to the cultivation of their own spiritual lives.

Thousands of Benedictine monasteries dotted Europe in the Middle Ages. But the Cistercian Order, established in 1098 and following the Rule, particularly emphasized cultivation of the land. Cistercians enjoyed the solitude and beauty of their monasteries’ pastoral settings. One chronicler described the Abbey of Rievaulx: “High hills surround the valley encircling it like a crown. These are clothed by trees of various sorts … providing for the monks a kind of second paradise of wooded delight.”

The most famous early Cistercian, Bernard of Clairvaux (1090–1153), emphasized that one could learn by laboring in the great outdoors “in the noonday heat, under the shade tree, [things] that you have never learned in schools.” The Cistercians nurtured the earth by draining swamps to reclaim land suitable for farming, helping to feed the growing population of Europe. Their innovation was so successful, and imitators drained so many fields, that modern environmentalists find themselves having to protect the world’s remaining wetlands. But in the Middle Ages, such methods kept many from starvation.

Thus both a philosophical theology of God’s self-revelation in creation and a hands-on practice of cultivating the earth played vital roles in the monastic culture for centuries.

Woman-of-all-trades

A contemporary of the early Cistercians, German abbess Hildegard of Bingen (1098–1179) was one of the most vibrant figures of the twelfth century. She wrote of the cosmos displaying God’s splendor: “the visible and temporal is a manifestation of the invisible and eternal.” Her understanding of creation as not just something given for our well-being but as a manifestation of God’s glory colored her robust approach to life. Hildegard wrote on the spiritual life, theology, natural science, and herbal medicine. She also penned the first known morality play and composed music and texts for liturgical works.

The Logos, said Hildegard, “brought forth from the universe the different kinds of creatures, shining … until each creature was radiant with the loveliness of perfection, beautiful in the fullness of their arrangement in higher and lower ranks.” Such a vision of creation charged with God’s glory energized Hildegard to write music and explore nature in practical ways.

Because she found the earth bursting with God’s life, she made careful study of plants and trees and their healing qualities (what today we would call homeopathic medicine). According to Hildegard, God’s divine radiance and fire fill the sun and air and flowers and water with viriditas—greenness and life. God’s Spirit gives life to each level in this great chain of being:

O fire of the Spirit, Comforter,

Life of the life of every creature,

Holy are you, giving life to all forms.

Hildegard valued her experiments in natural medicine as working with God’s created order. “All nature ought to be at the service of human beings,” she asserted, “so that they can work with nature since, in fact, human beings can neither live nor survive without it.” However, because of the Fall, “that Creation, which had been created for the service of humanity, turned against humans in great and various ways.”

Therefore in her Book of Simple Medicine, known today as the Physica, she set forth a catalog of plants, elements, trees, stones, fish, birds, animals, reptiles, and metals, detailing the poisonous properties of some and the healing properties of others. Ultimately Hildegard placed her study into its cosmic context. In the beginning all creation cascaded down from God’s splendor, she wrote; so the cosmos moves toward the last days, when God will purge away all darkness.

Following the beloved

By far the monastic figure best known for his appreciation of nature is Francis of Assisi (c. 1181–1226). Originally an unlikely candidate for an association with the humble creatures of the field, Francis was reared in wealth, wearing the finest silk clothes and best fashions of the day. After his conversion, however, Francis abandoned such luxury and adopted the simple life of poverty.

Sleeping on the ground in stalls intended for cattle, eating food donated by others, and donning the coarse brown robe and rope belt of peasants, Francis and the Friars Minor (Little Brothers) lived close to the earth. His later follower Bonaventure (see below) wrote of Francis, “In things of beauty, he contemplated the One who is supremely beautiful, and, led by the footprints he found in creatures, he followed the Beloved everywhere.”

Francis loved God’s creation, especially the wilderness where he could meet alone with the Lord. After full days of ministry—tending lepers on the verge of death or preaching from village to village—Francis would sneak into the woods to spend half the night in prayer. Often the friars went to search for him, only to find him rapt in God’s presence among the trees and animals. Several times each year he would pull away from ministry to take 40-day retreats at the Carceri, a woodland ravine nestled in the mountains several kilometers above Assisi.

In this wilderness setting, Francis and the other friars would pray as they consumed only bread and water and slept on the hard ground. In addition they traveled several times to Mount La Verna for extended solitude. There, among the rugged rocks, Francis had his most overwhelming encounter with God in 1224.

Known for preaching to a flock of birds and taming a wolf that had terrorized the citizens of Gubbio, Francis ultimately befriended all of nature. His famous “Canticle of the Sun” or “Canticle of the Creatures” (c. 1224) is a lasting tribute to God’s goodness in the world, indeed God’s presence in all creation. This hymn showers praise on the Most High, joining everything that God created, especially “Brother Sun” who gives light and reveals God’s radiance and splendor … and “Sister Moon” who is precious and beautiful.

As Francis lay dying, he requested to be placed naked upon the ground, in imitation of our Lord. Simple, poor, and embracing the earth, he repeated his beautiful canticle (sidebar) as he passed into eternity.

The ladder-climbing Franciscan

Born a few years before Francis’s death, Bonaventure (1221–1274) became the seventh minister general of the Order of Friars Minor and one of its greatest thinkers. In his short work on contemplative prayer, The Mind’s Journey into God (1259), this Franciscan scholar presented a progression of prayer in our ascent to God, beginning with the physical world.

For Bonaventure, “the universe itself is a ladder by which we can ascend into God.” Following the pattern spelled out by Pseudo-Dionysius many years before, Bonaventure described the whole cosmos—including the invisible realm of angels—as displaying God’s glory to us. Beginning at the lowest rung, physical creation, we can ascend to God, the source of all, in breathless contemplation, Bonaventure thought.

The first step of this devotional “Jacob’s Ladder” reflects on nature: the “origin of things … [that] proclaims the divine power … the divine wisdom that clearly distinguishes all things, and the divine goodness that lavishly adorns all things.” We see God’s attributes as we consider the multitude of created things, he wrote, observing their beauty and their order in the universe:

Therefore, open your eyes, alert the ears of your spirit, open your lips and apply your heart so that in all creatures you may see, hear, praise, love and worship, glorify and honor your God.

On the second rung of the ladder, Bonaventure said, we rise to see God’s essence, power, and presence manifest in all of nature. Here we not only see that God is Creator, we see “the invisible attributes of God” displayed in creation. We can do so because “these creatures are shadows, echoes and pictures of that first, most powerful, most wise and best Principle … signs divinely given so that we can see God.”

On the third and fourth rungs, we contemplate God’s image stamped in human nature, especially the faculties of our souls—memory, understanding, and will. From there we ascend through the contemplation of God’s one-ness, then his three-ness in the Trinity, and ultimately the ineffable presence of God. While Bonaventure’s devotional practice ultimately ushers us into a transcendent encounter with the Divine, he firmly planted it in a deep appreciation for creation, stemming from Francis’s love of natural beauty.

“So full of God is every creature”

The monastic emphasis on reading the book of creation continued. In the fourteenth century, Dominican preachers proclaimed God’s self-revelation in creation. Meister Eckhart (c. 1260–c. 1328) wrote: “Every single creature is full of God and is a book about God. Every creature is a word of God. If I spend enough time with the tiniest creature—even a caterpillar—I would never have to prepare a sermon. So full of God is every creature.”

His disciple, the mystic Johannes Tauler (1300–1361), built on Eckhart’s and Bonaventure’s writings. When we contemplate nature, declared Tauler, and see everything “blooming and greening and full of God,” we break forth in ecstatic joy.

From sixteenth-century missions in China to renowned universities today, Jesuit scholars distinguish themselves by their study of astronomy, biology, and other disciplines of science. Benedictines, Cistercians, Franciscans, and other orders continue to tend orchards, vineyards, woodlands, and pastures.

Writings of Thomas Merton and lesser-known nuns and monks in our own day challenge us all to care for God’s creation as we contemplate its beauty. Many monasteries offer retreats on their grounds and welcome others to share in daily reading of Scripture as well as reading from the “book of nature.” Ultimately they invite all Christians to join with them—and with believers over the past 20 centuries—in worshiping the Almighty as the heavens declare the glory of God. CH

This article is from Christian History magazine #119 The Wonder of Creation. Read it in context here!

By Glenn E. Myers

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #119 in 2016]

Glenn E. Myers is professor of church history and theological studies at Crown College and author of Seeking Spiritual Intimacy: Journeying Deeper with Medieval Women of Faith. He blogs on spirituality at Deep Wells.Next articles

All life has its roots in me

Hildegard personifies the fire of God’s Spirit in this excerpt from her Book of Divine Works

Hildegard of BingenCreation Care, Did you know?

Christians have praised the display of God’s presence in the natural world since the beginning of the church

the editors