The Jerusalem of the East

PROFESSOR CHO grew up in Pyongyang, the capital of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea—North Korea, as it is popularly known. A devoted patriot, he fought against United Nations forces for North Korea’s founder Kim Il Sung (1912–1994) during the Korean War (1950–1953). Following the war he left military duty, graduated from a university, and worked as a college professor for 30 years.

But upon his retirement, the dutiful professor and his family were expelled onto the streets. There is no word meaning “pension” in North Korean. Cho had enjoyed a comparatively high standard of living, but the “Arduous March”—the North Korean government’s name for the perfect storm of flooding, crop failure, and the collapse of Soviet support that devastated the country from 1994 to 1998—caused the economic situation of nearly all North Koreans to plummet.

The government, the sole supplier of food, stopped feeding all but a few of its 22,000,000 citizens. Factories shut down. Trains ground to a halt. Water was turned off. Deaths due to starvation may have exceeded 3,000,000. A new social class arose: Kotjebi, meaning “worthless birds.” These homeless North Korean children wandered the streets in packs.

These circumstances led more than 1,000 North Koreans to attempt to flee to South Korea through China every year with the assistance of South Korean missionaries. But North Korea’s army made this a dangerous undertaking. Only a comparatively small number survived.

Cho and his family were among the lucky ones. In March 2001, thoughts of imminent danger filled Cho’s mind as he gripped the hand of his adult son and sprinted toward the Tumen River separating North Korea from China. The chill wind pierced him to the bone. Thick ice had formed on the river, and snow on top of the ice buried his feet.

Almost immediately a dog began barking. A soldier with a rifle swung his searchlight along the riverbed. Cho and his son threw themselves down flat on the ground, motionless.

God remembers the poor

Suddenly the word “God” leapt into Professor Cho’s mind. Instinctively clasping his hands together, he cried out silently, “God, help me.” Just as quickly the soldier turned away, dog in tow. Professor Cho was certain that this was the work of God. Choked with emotion he whispered, “Thank you, God,” over and over.

Cho was a Communist Party member, pledged by North Korea’s Ten Principles to “make absolute the authority of the great leader comrade Kim Il Sung.” But deep within him was a nearly forgotten memory from childhood. A friend had once invited him to church, where he had heard of a God who loved him.

Cho was in middle school then, in the time before the Korean War when there were so many churches in Pyongyang that the city was known as the “Jerusalem of the East.” Crosses dotted the Pyongyang skyline.

Young Cho watched with curiosity the many evangelists on Pyongyang’s main street in the daytime shouting, “Believe in Jesus and go to heaven!” When one of Cho’s childhood friends invited him to church, he accepted. Church people welcomed him in, served him lunch, and gave him notebooks and pencils as gifts. He sang a song that he would remember 50 years later about how God always remembers the poor.

After his visit to church, young Cho eagerly shared the experience with his mother but begged her not to tell his father. But soon Cho’s father discovered the secret and scolded him harshly. His father said he would not forgive Cho if he ever went to church again. So Cho did not go to church or think about God anymore.

Cho’s father was one of the “original Communists,” a revered group who joined the Communist Party right after Korea’s liberation from Japanese colonial rule in August 1945. By party requirement the elder Cho detested religion deeply. As a reward he was permitted to live in Pyongyang—as long as he and his family stayed in the good graces of the government.

So the younger Cho grew up in the capital city of North Korea, witnessing firsthand the establishment of the Communist regime. When he watched North Korean propaganda movies, he cursed at the Americans he saw on the screen. He learned from the regime that American imperialism was North Korea’s greatest enemy and Christianity its preferred tool.

Christians represented the largest voluntary social group in Korea before the Korean War. There were more than 2,000 churches in the country in 1942, mostly Presbyterian and mostly in the north. After the 1945 partitioning of the country, the North Korean government attacked the church through its financial base. In 1946 it confiscated Christians’ finances through the Land Reform Act and in 1948 nationalized key industries, further weakening churches.

At the same time, Kim Il Sung nominated one of his (Christian) mother’s relatives, Pastor Kang Yang Wook, as a representative of the Chosun Christianity Federation, a group established to support the Communist Party while absorbing the existing Christian associations.

On September 9, 1948, the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea was officially established in the north. Government officials trumpeted the end of religion in North Korea. No more steeples. No more long-haired evangelists. No more notebooks or pencils or gifts. No God except for Kim Il Sung.

Escaping to the south

In late 1949, as the north was preparing for the Korean War, Communists arrested everyone who attended religious activities. They raided homes of Christians in search of religious books, which were regarded as “seditious [rebellious] circulars.” In a country where Japanese occupying forces had shut down 200 churches and arrested some 2,000 Christians a mere 20 years before, the season of martyrdom had returned.

By the time the Korean War began in June 1950, the government routinely arrested and persecuted Christian leaders on charges of sedition. During the retreat of North Korean troops, Kim Il Sung ordered the indiscriminate slaughter of Christians. There is no record of the number, but some estimate it in the tens of thousands.

Tens of thousands more escaped to South Korea, founding a number of churches (including Young Nak, one of the 40 largest churches in the world in 2014). Ultimately the refugees contributed to making South Korea the most Christian country in Asia.

Telling the story

Following the war the North Korean government prohibited rebuilding church buildings that had been destroyed. Churches in Cho’s neighborhood that were still standing were converted into schools or hospitals. That is how Cho and his fellow citizens came to forget about God. But as he held his son’s hand in the swirling snow of the frozen Tumen River, Cho had a revelation: like most North Koreans, he had forgotten God. But God had never forgotten North Korea.

Cho and many others escaped to safety in South Korea. While North Korea remains cut off from traditional journalism, historians are beginning to document the 100,000 Christians still living there.

In 2013 the North Korea Human Rights Record Center revealed detailed information drawn from surveying North Korean defectors in South Korea. Significantly more people had seen Bibles in North Korea than previously thought. But defectors also told a story of religious suppression: more than 60 percent of those caught in religious activity were sent to political prisoner camps.

But no matter how fierce the suppression, more North Koreans were beginning to call on the God whom they had forgotten. Cho and other North Korean defectors are now serving as missionaries; more than 200 defectors have graduated from South Korean seminaries.

Through shortwave radio broadcasts, balloon launchings of Bibles, and missionary trips, they are not a new trend in North Korean Christianity but the oldest Christian trend of all: ordinary men and women like Professor Cho who cannot help speaking about what they have seen and heard in the most closed nation on earth. CH

By Hyun Sook Foley

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #109 in 2014]

Hyun Sook Foley is cofounder and president of Seoul USA, a ministry serving the North Korean underground church, and author of The North Korean Hero’s Journey, which tells stories of Christian North Korean defectors.Next articles

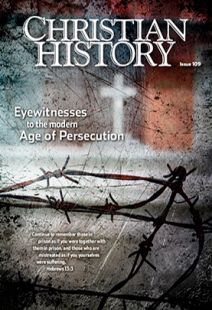

Eyewitnesses to modern persecution, Did you know?

Christians have suffered for their faith throughout history; here are some of their stories.

The editorsEditor's note: Modern persecution

What you will read in this issue is, in part, history that is still being written

Jennifer Woodruff TaitIs there a global war?

CH discusses modern persecution with John Allen Jr., the author of a new book, The Global War on Christians

John Allen Jr.