The “religion of geology”

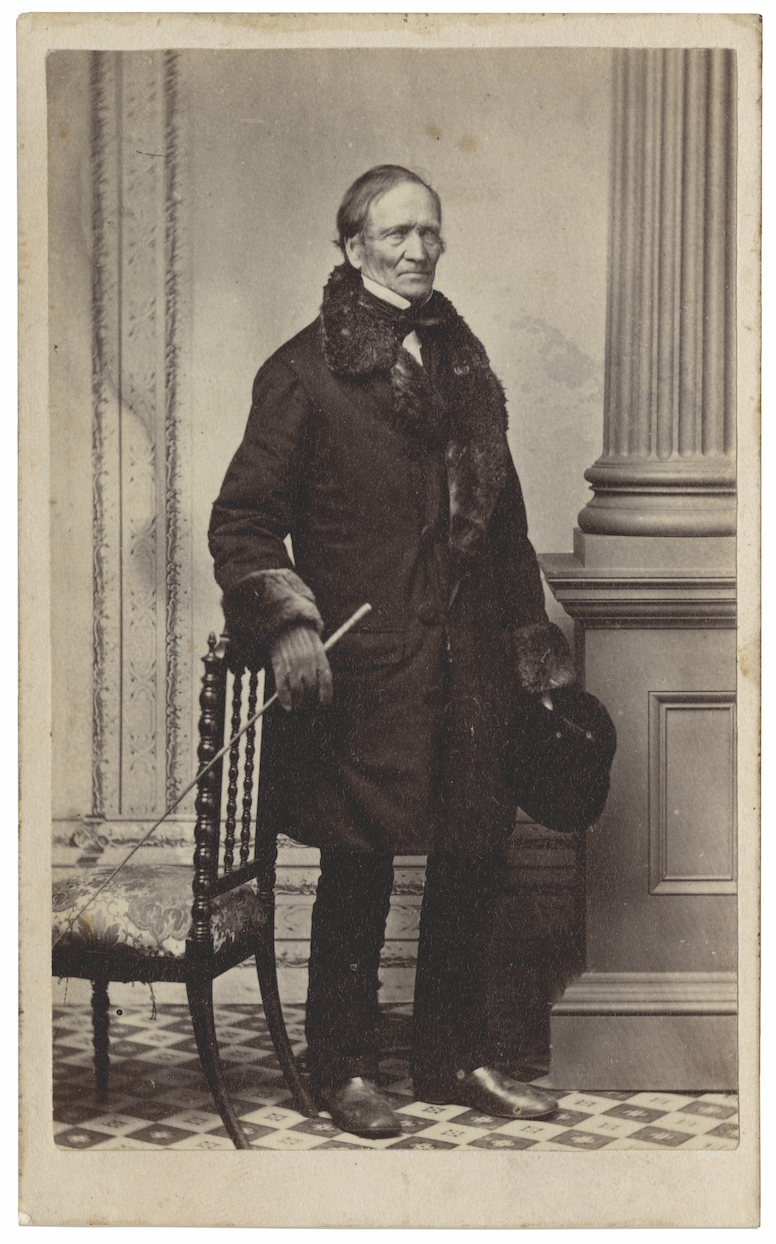

[Edward Hitchcock c.1863; Archives & Special Collections at Amherst College / Public Domain]

Edward Hitchcock (1793–1864) was the son of a poor farmer, hatter, and soldier in the American Revolution. In his twenty-first year, a serious attack of mumps damaged his eyesight permanently, ruining his plan to study astronomy at Harvard. It also left him with a heightened sense of his own mortality—at his death, funeral orator William Tyler said, “Throughout his entire public life he preached and taught as a dying man.” His brush with death brought him into a closer relationship with his father’s Calvinist branch of Congregationalism, instead of the Unitarian branch he had explored hitherto.

Despite his lack of college training, he became preceptor of his alma mater, Deerfield Academy, at 23. Two years later he left to study theology at Yale, where he also attended the lectures of Benjamin Silliman (1779–1864) on chemistry and geology.

A pious ally

In 1821 Hitchcock married Orra White. A prolific artist, she drew hundreds of images for her husband’s lectures, books, and articles, as well as illustrating the natural beauty of the Connecticut River Valley. That same year he was ordained a Congregationalist pastor, but ill health soon forced his church to dismiss him. After further study with Silliman, he was appointed professor of chemistry and natural history—a standard combination then—at Amherst College in 1825. Twenty years later he became president and professor of natural theology and geology. The change in titles indicates the importance of Christianity both to the man and to the institution.

Hitchcock served as official geologist for Massachusetts and Vermont, was first president of the Association of American Geologists, and was voted a charter member of the National Academy of Sciences in 1863. His Elementary Geology (1840), an enormously successful textbook, contained a chapter about the connections between geology and Christian beliefs. At the height of his career, he published The Religion of Geology and Its Connected Sciences (1851)—his most complete statement of natural theology, the subject closest to his heart:

Geology makes other economies of wide extent to pass before us, opening a vista indefinitely backward into the hoary past; and it is gratifying to witness that same unity of design pervading all preceding periods of the world’s history, linking the whole into one mighty scheme, worthy its infinite Contriver. . . .

Hitchcock vigorously promoted geology as a pious ally of the Christian:

Geology . . . was regarded with great jealousy, as a repository of views favorable to infidelity, and even to atheism. But if the summary which I have exhibited of its religious relations be correct, from what other science can we obtain so many illustrations of natural and revealed religion?

In the preface of the book, he spelled out a prophetic vision for Christian education. Given the use of science by skeptics as “batteries erected with which to assail spiritual religion,” would the Christian minister, only “slightly familiar with the ground chosen by the enemy be able not only to silence his guns, but, as every able defender of the truth ought to do, to turn them against its foes?” Surely, he said, the church “needs a professor of natural theology in our theological seminaries . . . to teach those who expect to be officers in the sacramental host how to carry on the holy war.”

Though he wrote frequently and with scientific precision about the vast age of the earth, Hitchcock rejected Darwin’s theory of evolution when On the Origin of Species appeared in 1859. Hitchcock died in 1864, but his favored interpretation of Genesis (the gap theory) together with his forthright defense of “the great fact of man’s creation” inspired conservative Protestants right down to the 1960s.

By Edward B. Davis

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #134 in 2020]

Edward B. Davis; adapted and reprinted from BioLogos.com with permissionNext articles

Drinking from a fount on Sunday

Michael Faraday’s experiments advanced the study of electricity

Geoffrey CantorFreedom from dualism

On several occasions Maxwell indicated his view on the relationship between his faith and physics.

Tom Topel“I know that my Redeemer liveth”

George Washington Carver sought to understand God’s creation and develop its benefits for others

Jennifer Woodruff TaitGod made it, God loves it, God keeps it

We talked to four scientists who are believers—three with distinguished careers and one embarking on the journey.

the editors and interviewees