“To love at all is to be vulnerable”

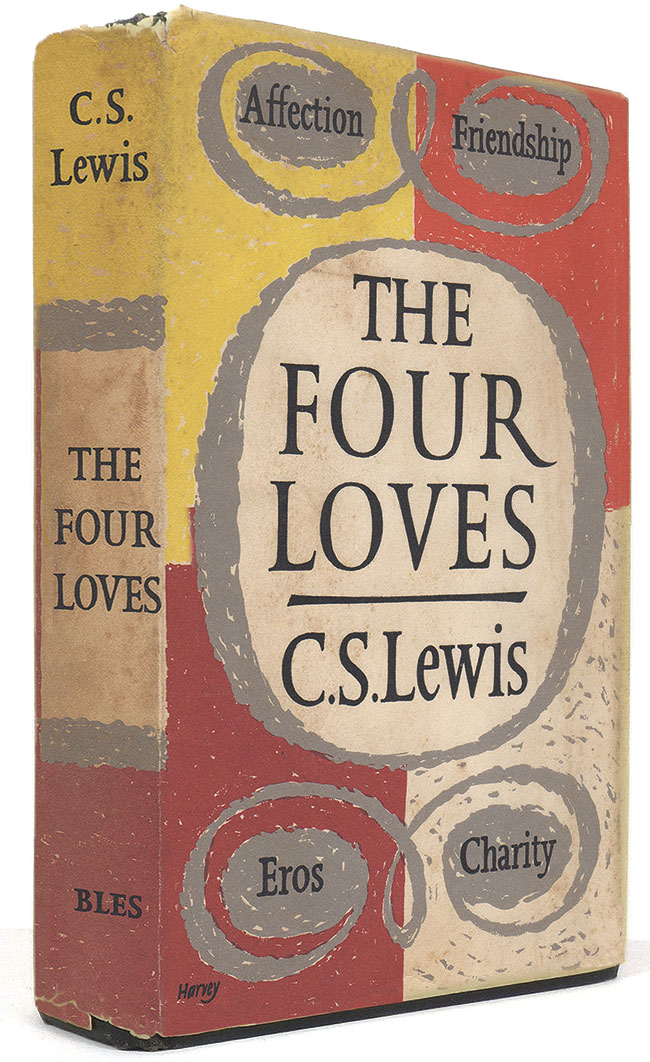

[Above: LOVE AND BROADCASTING The Four Loves was one of several books that Lewis based on lectures or radio talks. C.S. Lewis, The Four Loves, first ed., 1960—Courtesy of Matthew Farrelly.]

By the 1950s C. S. Lewis’s fame as an author, inspired theologian, and articulate communicator had caught the attention of Caroline Rakestraw (1912–1993), founder of the Episcopal Radio-TV Foundation. Rakestraw asked ERTVF board member Bishop Henry Louttit (1903–1984) to invite Lewis to deliver a set of radio talks for the Episcopal Radio Hour. Rakestraw and Louttit left the subject matter to Lewis’s choosing. “My dear Lord Bishop,” Lewis responded on May 1, 1958, “I think I can undertake what you suggest.”

The subject close to his mind at that moment, he noted, was “the four Loves—Storge, Philia, Eros, and Agape. This seems to bring in nearly the whole of Christian ethics.” Lewis had actually been mulling over thoughts on the subject for decades, having read the first part of Swedish theologian Anders Nygren’s (1890–1978) Agape and Eros (1930) in the mid-1930s; at the time, he wrote to a colleague about the book, “I must tackle [Nygren] again. He has shaken me up extremely.” References to his thoughts on Nygren and on love continue to resurface in his letters; in a letter only a few months after Lewis recorded the talks, he noted to an American professor of English, Corbin Scott Carnell (1929–2017), that Nygren’s book was among the relatively few modern ones that had influenced him. (He also made clear to Carnell that he did not agree with much of it.)

Ten talks become four loves

Lewis met Rakestraw in London and recorded “The Four Loves” in a single day on August 19, 1958. The 10 short talks were broadcast in the United States in 1959; that might have been the end of it, except that Lewis decided to turn them into a book. Though the book he wrote did not mention Nygren by name, Lewis implicitly critiqued Nygren’s approach of sharply differentiating what Lewis represented as “need-love” and “gift-love.” Of course, Lewis argued, the gift-love God has toward us is the highest form of love, but it is our need-love for God that drives us to him; “the highest cannot stand without the lowest,” as Lewis quoted from the Imitation of Christ by Thomas à Kempis (1380–1471).

Rather than Nygren’s twofold opposition of eros against agape, Lewis developed an outline of three natural loves: Affection (storge), Friendship (philia), and Eros (“that kind of love which lovers are ‘in,’”), and one divine love (agape or charity). When defining the three natural loves, he was careful to note how each reflects both need-love and gift-love, and how each could both serve as a means of approach to the divine—but if abused and wrongly indulged in, usurp worship and authority that belongs to God alone. “Love ceases to be a demon when he ceases to be a god,” Lewis quoted from the Swiss author Denis de Rougemont (1906–1985): adding that this could be “restated in the form ‘begins to be a demon the moment he begins to be a god’.”

One of the many fascinating things about the book is spotting the loves of Lewis’s own life as examples. Mrs. Fidget who “lives for her family” (whether they want her to or not) in Affection may be one of the many portraits of Janie Moore (p. 33) in Lewis’s works. Ronald and Charles, who show up in the Friendship chapter, are of course J. R. R. Tolkien and Charles Williams (see pp. 45–48)—and Lewis briefly, but touchingly, laments never again seeing Tolkien react to one of Williams’s jokes. While Lewis does not mention Joy Davidman by name in the chapter on Eros, he wrote after her death to American correspondent Donovan Aylard (1933–2019): “My married life was very short; it surpassed in happiness all the rest of my life. You’ll find anything I have to say about marriage in my The Four Loves.”

Lewis’s ultimate goal, of course, was to root our experience of these natural loves in our experience of divine agape. There, and only there, he argued, do they find their proper place and their ultimate fulfillment. In heaven, he concludes, we will not abandon all our “earthly Beloveds,” but will find them in Christ: “By loving Him more than them we shall love them more than we do now.”

Yet one of the book’s most penetrating passages speaks not of agape’s ultimate fulfillment, but of what we may endure on the way: “To love at all is to be vulnerable. Love anything, and your heart will certainly be wrung and possibly be broken.” Only by that vulnerability, only by that death and breaking that leads to life, can we learn to love as Christ loves, and to love Christ by loving our earthly beloveds well.

By Jennifer Woodruff Tait

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #140 in 2021]

Jennifer Woodruff Tait is managing editor of Christian HistoryNext articles

“A long line of bookish people”

Lewis’s parents and extended family shaped his intellectual and artistic pursuits

Crystal HurdJack's journey

Major events in the life of Jack Lewis and his family and friends—and some of his most famous works

the editors