A tour of ancient Africa

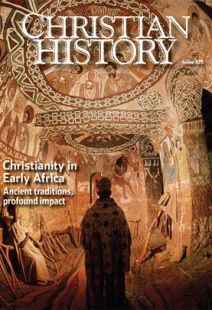

IT IS THE MORNING of November 30 in the small town of Aksum, nestled in the high mountains of northern Ethiopia not far from the Eritrean border. In the past few days Aksum has been overrun by pilgrims making their way from all corners of the Ethiopian highlands and from Ethiopian communities overseas. They have come to celebrate the Feast of Maryam Zion.

Sitting in the ancient seat

Last night the devout thronged round the eucalyptus-shrouded compound of the Old Cathedral of St. Mary of Zion, which, at a distance, looks rather like a castle. At the all-night service the air was thick with incense, much banging of drums, and the rhythmic chant of ancient liturgy in the Ge’ez language.

In the morning, with the sun warming the chill highland air, the patriarch of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church (called Abba or Abuna, meaning “father”) is enthroned ceremonially. He is seated in front of a granite memorial slab, or stela, commemorating one of Ethiopia’s last pre-Christian kings. Every year it is a strange combination: the head of one of Africa’s most ancient churches seated next to a pagan funeral monument from the great Aksumite Empire.

That empire dominated this region of East Africa from approximately 100 BC to AD 600. It became Christian in 340—when Christianity in the British Isles, already limited to a small number of people under Roman rule, was about to disappear into almost 300 years of Anglo-Saxon paganism.

Christianity was established in northeastern Africa well ahead of most of the Roman world, and this is no better witnessed than at Aksum. Aksum is to the Ethiopian Orthodox Church what Rome, Canterbury, or Constantinople are to Catholics, Anglicans, and Eastern Orthodox: the home of the Mother Church.

What can archaeology tell us about this ancient, diverse expression of the Christian faith? Archaeology is not history. Archaeologists do not rely upon the written text alone to make sense of the past, although it is a valuable tool. Archaeologists deal with tangible things—rubbish, it is often unfairly said. But they also deal with people, by allowing ancient objects to speak on their own terms.

Regarding early African Christian history, archaeologists have rich and diverse materials to work with. There are written inscriptions, called “epigraphic.” There is architecture such as church buildings and baptismal fonts. There are funerary remains—Christian burials, with their east-west orientation and lack of objects buried with the deceased, are very distinctive. Finally, there are smaller items such as crosses, prayer books, and frescoes (wall paintings done on fresh plaster).

Stories in stone

Let’s take a tour of African Christianity from north to south and look at its material remains in North Africa and Egypt—some of the earliest and most magnificent examples of Christian art and architecture on the African continent.

Nowadays we think of North Africa (the “Maghreb,” including Algeria, Libya, and Tunisia) as solidly Islamic. But Islam reached these areas only in the seventh century. Prior to that time North Africa was home to one of the most dynamic, vibrant, and numerous Christian populations anywhere in the Roman Empire. We know this today through the work of archaeologists who have described an impressive picture of daily life in North African communities.

Christianity was an “underground” religion in much of the Roman Empire, and this is reflected in the relative invisibility of early Christian archaeology. Small house churches rather than great monumental statements in stone were the norm for at least the first three Christian centuries.

Many of these archaeological remains tell stories of martyrdom. Prior to the Edict of Toleration (311), which agreed to treat Christians with benevolence in the Roman Empire, Christians were at considerable risk of dying for their beliefs. Massacres of Christians were common and keenly felt in North Africa.

Memory of the martyrs

This force of memory was particularly strong for the Donatists, a breakaway Christian group that emerged in the fourth century (see “See how these Christians love one another,” pp. 29–33). Donatist inscriptions on their own churches directly stress their own holiness and that of their martyrs, which they perceived to exceed that of the mainstream church.

When Christianity became tolerated, Christians began to build large buildings. At the city of Timgad in Algeria, and in other ancient Roman cities such as Carthage in Tunisia, and Sabratha and Lepcis Magna in Libya, huge and well-appointed basilicas date from the fourth century onward, much like those found in any Roman city.

The basilica is a standard church plan, possibly derived from Roman secular buildings, used in the building of churches today all over the world. It features a central nave, or open space, with aisles along the sides and an altar at the east end. The altar is often within a semicircular alcove.

Ancient North African basilicas have large, many-sided, well-decorated baptismal fonts. Rich mosaic work, drawn from a strong classical (Roman) tradition yet with recognizable Christian imagery, covers these grand structures.

Egypt vs. Constantinople

While the rich Christian culture of northern Africa disappeared in many areas after the Arab conquest of the seventh century, Christianity survived and briefly flourished in one area: Egypt.

According to apostolic tradition, St. Mark brought Christianity to Egypt in the 40s (see “Some others you should know,” pp. 36–37), and he is still reckoned as the first pope of what would become the Coptic Church. “Coptic” comes from the Arabic term for “Egypt,” qibt, which is used interchangeably to mean “Christian.”

The Copts of Egypt rank among the great survivors of history. Along with the churches of Ethiopia and Syria, the Coptic church was regarded historically by the mainstream church as heretical, since it did not agree with the complex definition of the nature of Christ put forth at the Council of Chalcedon in 451. This definition was advanced by the Byzantine Empire (the eastern half of the Roman Empire, still in existence after the western empire had collapsed) and its Greek-speaking churches, the ancestors of those churches we today call Eastern Orthodox.

Part of the issue was political. The Byzantine Empire was based in Constantinople, while the Copts saw themselves very much as Egyptians. The Arab conquest brought matters to a head, and the position of the Greek-speaking Christians in Egypt massively eroded after the Arab conquest, although small populations remain today in Alexandria and Cairo.

Initially Copts thrived under Islamic rule. Their craftsmanship as architects and wood carvers was in great demand by the Islamic conquerors, and many early mosques in Cairo show the workmanship of Christian artisans.

The Coptic language soon died out in everyday use, though it remained a liturgical language. In medieval Bibles and missals (liturgical texts), Arabic and Coptic appeared side by side.

Getting away from it all

In Alexandria, Egypt’s first city, which had a large Jewish population, Christianity had long found a ready environment in which to flourish. After Constantine’s Edict of Toleration, large churches were established on the sites of pagan temples. Christian burials dominated the underground catacombs, marked in many cases by simple crosses. Christian names, such as Paul, became widespread.

Out in the Egyptian countryside, an impulse toward the monastic lifestyle was growing (see “Become completely as fire,” pp. 15–17). Anthony (ca. 251–356) and Paul (d. 341) are regarded as the first Christian hermits. But their desire to get away from the cares of society and lead a devout life dedicated to God was influenced by much earlier pre-Christian practice of looking for the divine in the desert.

The lingo of early African monasticism evokes its severe landscape. Hermit derives from a Greek word for wilderness; ascetic from another Greek term for spiritual training. An anchorite was an individual who departed for the countryside to get away from urban life and its distractions. Remains of small cells and caves are still found all over Egypt, and the depictions of Anthony and Paul in frescoes and icons in churches attest to the fame of these early Christian spiritual superstars.

But it wasn’t all about the solitary life: the desert also produced communal monasticism, which we recognize today as the more conventional form of Christian ascetic life.

St. Pachomius (ca. 292–348), a former soldier, became a hermit and then founded at Tabennisi and later at Pbow communal monasteries. By the time of the Arab conquest in the mid-seventh century, monasticism was widespread in Egypt. Today archaeologists are still digging up large and important monastic sites at Bawit, Saqqara, and Anba Hatre.

Common features of these sites include cells, refectories (cafeterias), gardens, and oil presses, as well as a number of monastic churches. These monasteries were often surrounded by large enclosing walls, initially to keep the outside secular world at bay, but later as a defense against attack by desert tribes. Soon wary monks added massive castlelike ksars (fortified towers).

Today we can still walk through these historic ancient monasteries in the Wadi Natrun, just to the south of Alexandria, and over by the Red Sea. The large monasteries of St. Paul and St. Anthony still attract devout pilgrims and a small flow of young Christian men eager to follow in the ancient monastic tradition of Egypt.

“Old Cairo”

At Kellia, just to the south of Alexandria, a hybrid of solo and group monastic life developed. Here, from the fourth century until the ninth, monks lived in small compounds, each with one or two living rooms, a small kitchen, wells, a garden, and a chapel. The monks ventured out on weekends to communal churches to celebrate the Eucharist.

Other ancient Christian sites in Egypt also bear witness to the African heritage. Cairo is a relatively recent city built on Islamic foundations, but the churches of “Old Cairo” still usher visitors and worshipers into more ancient, and distinctively Egyptian Christian, spaces.

Their sanctuaries are closed off behind a screen crowded with icons. Men and women are segregated in the main body of the church. In Bagawat we can see how Christians were buried by looking inside Christian mud-brick tombs (mausolea, from which we get our word “mausoleum”) decorated with painted ceilings showing Old and New Testament scenes.

Rising from the desert of Mareotis, southwest of Alexandria, is the great monastic city of Abu Mina. Once, before the Arab conquest, Abu Mina was one of the greatest pilgrimage centers of the Christian world.

The shrine of the martyr St. Menas forms its heart. The folk memory of martyrdom is so strong in Egypt that Copts reckon the start of their calendar from the date that Diocletian, one of the worst of the anti-Christian Roman emperors, came to the throne in 284.

Menas’s simple burial chamber soon became enriched with the addition of a huge basilica over the shrine, paid for by Emperor Justinian (482–565). Excavations by the German Archaeological Institute uncovered a range of structures such as xenodochia (“guest houses”; see issue 101, Healthcare and Hospitals in the Mission of the Church), hospitals, and palaces where officials and churchmen lived.

Pilgrims to the shrine brought back oil or holy water in ampullae (small earthenware flasks). Digs have turned up these bottles from the eastern Mediterranean, throughout much of the European continent, and as far northwest as Meols near Liverpool in England.

Along the Nile

We may read another story written on the landscape of the modern-day Sudan, beyond the Roman world of North Africa and the Nile. There, three medieval states once existed: Nobadia, with its capital at Faras in the north; Makhuria, with its capital at Old Dongola; and furthest south Alwa, with its capital at Soba (see map, pp. 22–23). In the 1960s Lake Nasser flooded the area, but before that, extensive archaeological work by a Polish team uncovered a city with a number of churches. Tradition tells us that Nobadia was evangelized by representatives of Emperor Justinian’s wife, Theodora, who was an anti-Chalcedonian Christian despite her high-ranking position in the Byzantine Empire.

The large cathedral at Faras, now destroyed by flood waters, contained a wonderful cycle of many-colored frescoes depicting a range of Old Testament characters, as well as a local princess and local bishops.

Further south at Old Dongola, the remarkable Church of the Granite Columns, the cathedral at Soba, and a monastery all bear witness to the flourishing of Christian culture here from 500 to 1200, when Islam finally drove Christianity from the middle Nile.

Christian communities survived, though, in the Ethiopian highlands, where King Ezana of the Aksumite Empire had been converted to Christianity by a Syrian Christian in 340 (see “From Abba Salama to King Lalibela,” pp. 18–21). Funeral inscriptions proclaiming allegiance to the Christian God replaced the older-style granite stelae at Ethiopian gravesites. Coins that bore the motif of a king holding a fly whisk beneath a crescent moon (symbol of the moon god, Almaq) gave way to a king holding a cross.

Perched on a mountain top east of Aksum, where we began, is the ancient restored church of the monastery of Debre Damo, bearing witness to a strong and still-living monastic tradition developed here in the sixth century. In time, Aksumite churches gave way to another strong Ethiopian cultural tradition, the rock-cut church (see “From Abba Salama to King Lalibela”).

But the most intriguing Christian artifact in all of Ethiopia, and perhaps all of Africa, is found in the little monastery of Abba Garima near the town of Adwa not far from Aksum. Here, an illuminated biblical manuscript, written on goatskin parchment, has recently been dated to between 330 and 650. It is thus one of the earliest, if not the earliest, Christian illuminated manuscripts anywhere in the world. Through it we hear a distant echo of a storied past—the ancient, culturally rich tradition of an African faith that still lives today each year as drums bang and incense wafts to God, the Lord of Nations. CH

By Niall Finneran

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #105 in 2013]

Niall Finneran is reader in medieval and historical archaeology at the University of Winchester, UK.Next articles

Become Completely as Fire

Early Egyptian monastics left an enduring legacy of interior watchfulness and prayer

Michael BirkelEarly African Christianity: Did You Know?

Fascinating facts and firsts from the early African church

the EditorsEditor's note: Early African church

In this issue we walk through everything from ancient archaeological ruins to modern-day worshiping communities

Jennifer Woodruff TaitListening to the African witness

Two modern scholars reflect on Christianity in Africa, then and now

Jacquelyn Winston, Lamin Samneh, and the Editors