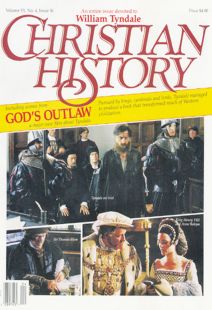

William Tyndale: A Gallery of Characters in Tyndale’s Story

Sir Thomas More

One of William Tyndale’s bitterest opponents, and one of the best-known men in 16th-century England—for his power, his intellect and his religious convictions. His was the central character in the prize-winning play and movie, A Man for All Seasons. A devout and intelligent Roman Catholic layman, he was appointed to the post of Lord Chancellor, then was commissioned by the king and the church to refute William Tyndale’s arguments and to discredit his character. He wrote nine books against Tyndale, filling more than 1,000 pages with arguments and invective against the reformer, and always defending the ultimate authority of the pope and the Roman Catholic Church (see “The Pen-and-Ink Wars,”).

Ironically, though More had many people executed because they denied the pope’s authority, his immovable commitment to that authority eventually led to his own death. When King Henry insisted on getting a divorce contrary to papal proclamations, then went on to declare that the pope no longer had authority in England, More told the king that he disagreed and would have to resign his post. Henry could not tolerate the public humiliation of having his closest advisor visibly questioning his wisdom, so he had More executed on trumped-up charges.

Cuthbert Tunstall

The bishop of London to whom Tyndale went in 1524, seeking patronage for his work of translating the New Testament into English. As far as the church hierarchy went, Tunstall was a shrewd choice on Tyndale’s part. Tunstall was a learned man, a language scholar of some ability himself, and he had declared his affection for some of Erasmus’s reform oriented ideas.

But Tyndale’s request came at a time when things done in the name of reform were creating havoc in Europe: violent riots; overthrows of local authorities; attacks on clergymen . . . . So Tunstall was leery of anything that smacked of “Lutheranism,” and it was Luther’s common—language German version of the New Testament that figured prominently in the sources of the havoc. No matter how intelligent or concerned for scholarship he was, he was at that time unready to support any New Testament translation work, and so sent the young translator looking elsewhere for patronage. Later, he can be seen burning Tyndale’s testaments and other pro—reform literature. Apparently politics had won out.

Anne Boleyn

This French-trained English beauty was indirectly a friend to William Tyndale, though unfortunately for both her and Tyndale, she was not enough of a friend to her husband the king. This lady-in-waiting probably first came to Henry’s attention about 1527, after his repeated attempts to conceive and raise up a healthy son with Catherine had aged her and frustrated him. So while he pursued getting a divorce from Catherine, he was also pursuing the affections of Anne. She teased him, but would not give herself to him until he had the divorce and married her. This done, she became queen. During her brief reign as queen (1533–36), she managed to lay hands on an ornate copy of Tyndale’s 1534 edition of the English New Testament, as well as a copy of his “heretical” The Obedience of a Christian Man that she showed to Henry.

The king loved it, and for a time wanted Tyndale to be his court propagandist. But in the meantime, Anne was unable, like Catherine before her, to produce a healthy male heir. Plus, her prima donna attitude alienated many in the court, and some of them told the king of her sexual philandering with other men. Already disappointed in her, the incensed Henry had her quickly executed and the marriage declared void. Anyway, he had already set his eye upon Jane Seymour, and with Anne out of the way she soon became Henry’s third wife.

Thomas Wolsey

This power-hungry son of an English butcher became chaplain to the Archbishop of Canterbury at age 30, and chaplain to Henry VII at 34. Under Henry VIII’s sovereignty, at age 44 he rose to Cardinal, and at 54 became the pope’s personal representative in England. The corruption in his heart apparently went deep; he accumulated property and fineries that were exceeded in luxury only by King Henry’s, and was well-known for having at least one “wife” and two or more illegitimate children. He became the king’s right-hand man in several arenas, but especially in negotiating with the pope to get the king’s way. Opposing and persecuting refomers was just another way to keep both king and pope happy and united against a common enemy. Unfortunately for Wolsey, he was unable to secure papal permission for Henry’s divorce from Catherine quickly enough, and so was sentenced by the king to die “for treason.” Just past 61 years of age, he died of fright and heart failure en route to his execution.

Bishop Stokesley

The bishop of London after Cuthbert Tunstall, he became infamous as one of the cruelest opponents of Protestantism to ever hold church office in England. He was responsible for the martyrdoms of even more Protestants than Sir Thomas More, and was very likely the one who financed Henry Phillips, the man who searched Tyndale out and betrayed him.

The Poyntzes

The English couple who took Tyndale in, when he was fleeing various agents of the king and the church, and gave him quarters at the English merchants’ lodgings in Antwerp. Thomas Poyntz was related to Lady Anne Walsh. During Tyndale’s stay with them, the Poyntzes encouraged him, gave him a place to study, guarded his secrecy, and warned him of their fears about Henry Phillips. After Phillips betrayed Tyndale, Thomas worked diligently trying to secure Tyndale’s release, and himself was imprisoned for his persistence and his pro-reformation sympathies.

H. Monmouth

Humphrey Monmouth was the London businessman who took young Tyndale in and briefly gave him lodging, before the translator abandoned hope of translating the New Testament in England and headed for Europe. Apparently a good-hearted Catholic who only briefly flirted with Protestantism, he later suffered appreciably for that flirtation; he was brought to trial by the church for harboring the “heretic.”

Miles Coverdale

A translator/scholar who Tyndale befriended at Oxford, he later helped Tyndale with his always continuing revision work on the New Testament translation. After Tyndale’s death, it was an entire English Bible with Coverdale’s name on it that Henry VIII officially approved to be spread “among all the people.”

John Frith

One of Tyndale’s closest friends, and like Tyndale, one of England’s ablest scholars, also educated at both Oxford and Cambridge. Three or four years younger than Tyndale, Frith probably sat at Tyndale’s feet in the reform-oriented Bible studies that Tyndale led at Oxford, then later Frith was, like Tyndale, pursued around England and Europe for his reformation and translation efforts. A priest who married, Frith was captured and martyred some three years before Tyndale. One of Tyndale’s Scripture-filled letters to the imprisoned Frith includes the encouragement that Frith’s wife was “well content with the will of God, and would not for her sake have the glory of God hindered.”

John and Anne Walsh

Sir John and Lady Anne Walsh were the masters of Little Sodbury, the estate where Tyndale worked briefly after leaving Cambridge, probably as a tutor to their two young sons. They were known in the region for their hospitality to both nobility and clergy; it was at their table that Tyndale challenged a visiting cleric, “If God grant me life, ere many years pass I will see that the boy behind his plow knows more of the Scriptures than thou dost!” Exposed to reformation thinking by Tyndale, the Walshes gave him money to support himself in Europe, and later made efforts to get him released from Vilvoorde prison.

Thomas Cromwell

He succeeded Sir Thomas More as chancellor to the king, and tried to be a friend to Tyndale when the reformer was sitting in prison. He is best-known for carrying out King Henry’s order to suppress the monasteries in England, then for being executed by the king soon after the last monastery had surrendered. A man of Protestant sympathies, he attempted to get Tyndale set free from Vilvoorde prison by contacting the governor of the prison. He was obviously not successful, but he was successful in convincing the king to approve distribution of the English Bible translated by Tyndale and Coverdale.

By the Editors

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #16 in 1987]

Next articles

What Tyndale Owed Gutenberg

Without Gutenberg, Tyndale’s “revolution” would have been impossible.

Raymond A. LaJoieChristian History Timeline: William Tyndale

Chronology of events associated with William Tyndale.

the Editors