She would follow only Christ

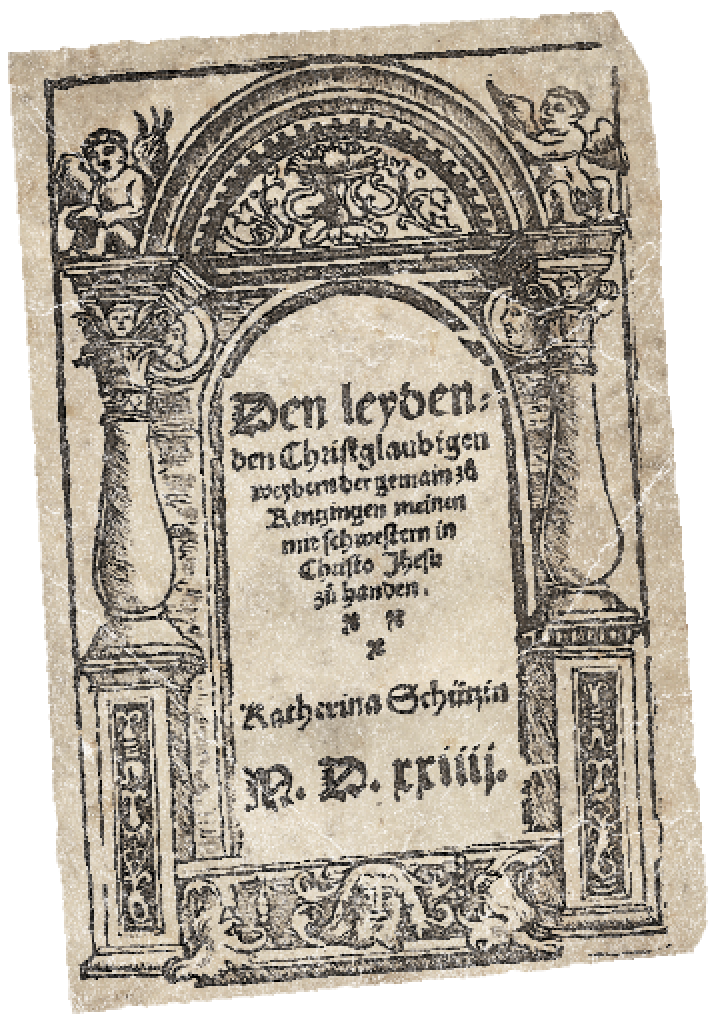

[Den Leyden... A Katharina Schütz Publication]

KATHARINA SCHÜTZ ZELL (c. 1498–1562) was reared as a faithful member of the church in Strasbourg, a city that manifested the ecclesiastical problems and the reforming spirit of the late medieval and early modern world. By her own account, the young Katharina Schütz was actively devout and spiritually anxious; she attended the sacraments, did good works, led other women in religious activities, and even read the Bible in German (which the clergy did not encourage!), but she could find no assurance of her salvation.

Then she heard the teachings of Martin Luther, spread in Strasbourg by Matthew Zell, in late 1521 or early 1522. Zell’s teaching convinced her that she was saved by faith, by the grace of trusting in Christ alone, without her own works or the merit of anything created (including the sacraments).

This new teaching did not turn Schütz away from the church, but gave new life to her commitment and transformed her religious vocation. Still dedicated to God, she no longer felt she had to earn God’s approval: according to her new understanding of Scripture, God freely accepts those who trust his son alone and that trust is God’s gift, not human doing. No one needs any human intercessor or ritual mediation.

As a member of this priesthood of believers, laywoman Schütz felt herself called to be a “fisher of people”; she would tell others how they could be saved, according to what she had learned from the Bible by the illumination of the Holy Spirit, through the words of Luther, Zell, and others. She would use her pen, her voice, her home, and her very self to fulfill that calling.

Mother of the afflicted

Schütz’s outward life soon changed as radically as the inward: she wed pastor Matthew Zell on December 3, 1523. (As with many early modern German women, she was often referred to by her former last name, which we will use here for clarity.) In Strasbourg the new movement had begun to take hold seriously only a little more than a year earlier, so both were putting themselves at significant risk. For priests to marry was to court Catholic condemnation, but Protestants saw these marriages as a witness to the Bible’s authority over “human-devised” teachings of church tradition.

Clergy who determined to marry had to find women willing to be labeled immoral for living with priests; today the courage of these women has mostly been forgotten. Some pastors married their housekeepers, regularizing long-term relationships. Schütz was (to her knowledge) the first respectable woman in Strasbourg to marry a priest. Zell was not just any priest, but the one leading the Protestant “heresy,” so his new wife soon experienced scandalous rumors and slander.

Confident of the rightness of her position, she wrote to Strasbourg’s bishop defending clerical marriage on the basis of Scripture, later published as the Apologia for Matthew Zell on Clerical Marriage (1524). Besides her own justification for exchanging the celibate holy life for a married holy life, her intriguing text includes a creative, biblically based argument for a layperson, a woman, speaking out publicly.

This was far from the only religious conflict, however. In July 1524 Catholic overlords forced 150 men in nearby Kentzingen and their pastor, Jacob Otter, to flee. They took refuge in Strasbourg, the nearest city with Protestant sympathies; the Zells welcomed 80 into their large parsonage and helped feed them for four weeks. This was only the beginning of a lifelong practice of receiving travelers and refugees, a ministry dear to both husband and wife. Besides looking after those who had fled, Schütz was concerned about those who had been left behind. Her first printed pamphlet was a Letter of Consolation to the Suffering Women of Kentzingen (above at left).

A fellowship of mutual love

Their marriage also established one of the first Protestant parsonages, with important consequences for Schütz as one of the first examples of that new female calling: the pastor’s wife. Roman canon law taught that marriage was a sacrament, a mirror of the relationship between Christ and the church. Its primary purpose was procreation, but it was also a means to prevent sexual sin; those who could do without this “concession” were considered more holy.

Protestants clearly insisted that marriage was not a sacrament but a fellowship for procreation and for avoiding fornication. Strasbourg’s reformer Martin Bucer (1491–1551) regarded marriage as a covenant; he added a third reason as the most important—a personal relationship of “mutual love.” In Strasbourg where Bucer’s ideas first spread, newly married priests and their wives were particularly visible models of that mutual love in “holy households,” which would become the ideal pattern for families.

Like Schütz, Zell came from Alsace and from a substantial artisan family. An educated man and the most popular preacher in the city as well as the first Protestant pastor, he became one of the leading figures of the church. His wife also became acquainted with individuals from higher social ranks than those she had known as a girl—something not possible for housekeepers of earlier priests or even respectable citizen-wives among the “common people.” Once an obscure young woman known by name probably only in her home parish, she became a recognized figure in the city of Strasbourg and among Protestant associates of her husband in Germany and Switzerland.

Despite the fact that he was 20 years older and better educated, Zell regarded Schütz as a partner in faith from the beginning and increasingly accepted her cooperation in his ministry as well; he called her “wedded companion,” “mother of the afflicted,” and “assistant.” The last exasperated critics. Protestant pastors’ wives of the first generation were often remarkable people who regarded their marriages as religious callings, but most couples expressed this vocation in more conventional ways than the Zells.

Bucer thought Schütz had undue influence over her husband when in the early 1530s she vigorously encouraged Zell in his rejection of the custom of godparents because it was not biblical. The point was resolved peaceably, but Bucer apparently felt that guiding Zell would be easier if Zell’s wife were not pulling in the other direction. Despite their exasperation with her independence, however, the first-generation reformers never doubted the orthodoxy of her faith, and they consistently appreciated her service to the needy.

Practical reasons freed the two to work together. Their two children died very young, and although her household included young relatives or students at various times, Schütz had more time to share her husband’s work than did some fellow clergy wives. She deeply mourned the loss of her children, and their memory no doubt contributed to her concern for other children.

“Burst forth in song“

The new perspective Zell and his colleagues preached brought significant changes to the shape of belief and practice; among the most visible were the altered forms, language, and character of public worship. Many people welcomed less formal German services, celebrated in more austere buildings with regular biblical preaching, corporate practice of the sacraments, and a voice in the prayers for everyone through song.

However very few songs met the standards of the new clergy—creating the problem of what to sing or pray at home, as old hymns to the saints were banned. In this context Schütz edited a version of the Bohemian Brethren hymnbook. Controversial Silesian nobleman Caspar Schwenckfeld (c. 1489–1561) probably brought her the book on one of his visits; her chief contribution was a vivid little foreword. The songs of the Brethren were generally acceptable in Strasbourg, but Schwenckfeld, their sponsor, was not, and the book was never republished.

In the 1530s reaction against Roman Catholicism developed into new church institutions, and Strasbourg’s leaders began to banish those who did not accept Protestant forms of worship, although they stopped short of executing dissidents. The Zells, however, continued to befriend and receive all kinds of people—against the wishes of Bucer, now Strasbourg’s leading theologian, although Zell remained the most popular preacher.

These tensions rose to dangerous levels in the 1540s and finally to war in 1546. The Protestant Schmaldkaldic League was defeated in 1547, and negotiations

with victorious Holy Roman Emperor Charles V worked out a truce, the Augsburg Interim. When its provisions took effect in 1548, Strasbourg found itself once again a city where the Mass and other Roman sacraments were celebrated and Roman priests moved through the streets.

The elderly Zell strongly opposed compromise, but his fiery sermons ended with his death on January 10, 1548. Schütz was devastated to lose her beloved husband and pastor, especially at a time of such religious danger. At the burial she unexpectedly preached a sermon, recounting his life and death and urging his parishioners to hold faithfully to his teaching. Following his death she also privately wrote for herself a series of meditations on the book of Psalms, pouring out her grief over the loss of Zell, and the effects of the Interim on the gospel and church to which they had devoted their lives.

As a widow Schütz continued to love and serve the church and the people in Strasbourg, but by the 1550s she was living in a changed world. Almost all the leaders with whom she had shared the early days of reform were dead. Most of the city’s new ministers were shaped by increasing confessional divisions pitting Protestants against one another, against Rome, and against Schwenckfeld and Anabaptist groups who did not agree with any of the established churches.

Schütz herself steadfastly refused to take sides against any who had broken with Rome as long as they held to the essential teachings of Christ as the sole Savior and to Scripture as the sole authority. She disagreed with Anabaptists on some points but admired the ethical discipline that most of them demonstrated and thought they certainly should not be persecuted.

On the defensive

In the 1550s Schütz found herself defending her faith on two fronts. One party was Schwenckfeld’s circle of disciples in the city, who claimed her as one of their own but criticized her for not conforming. Schwenckfeld himself in 1551 publicly claimed Schütz as his supporter, which apparently led to an estrangement between them. In 1553 she wrote him a long letter to make clear her appreciation for his gifts and her determination not to be claimed by his or any other party.

The second generation of Protestant ministers in Strasbourg also considered her a Schwenckfelder despite her expressed objections. While her argument with the Schwenckfelders was not known beyond their circle (and apparently deliberately forgotten there), Schütz’s dispute with Strasbourg clergy became public.

She finally felt compelled to publish her correspondence with Zell’s successor, Ludwig Rabus (1523–1592), to enable her fellow citizens and church members to draw their own conclusions. Was she an apostate inspired by the devil who had always troubled her husband and the church, as Rabus said, or was she in fact a better representative and voice for the first-generation reformers than he was?

In the last of her publications, Meditation on Psalms and an Exposition of the Lord’s Prayer for Sir Felix Armbruster (1558), she prepared a printed form of the counsel she had been sharing for so many years. The book included a letter of consolation for an elderly friend suffering with what was then called “leprosy.” In Sir Felix’s isolation, his old pastor’s widow, one of his very few visitors, had become his pastor.

The last years of Schütz’s busy life carried on the same traditions of ministry that had always marked it. She cared for her extended family, especially a handicapped nephew for whom she had been responsible for many years. She helped the needy, both individually and by shaming the government into reforming its home for poor and sick Strasbourgers. She continued to teach and comfort those who came to her and to insist on doing what she believed was right, no matter how controversial.

In the months before her death, Schütz preached at the burials of two women friends who were Schwenckfelders; their families did not want the city clergy to call them heretics. Controversy surrounded her own burial because Strasbourg clergy considered her a Schwenckfelder, but her friends and family rallied. Conrad Hubert, Bucer’s secretary and the only remaining first-generation minister, reluctantly agreed to defy the ecclesiastical establishment and to preach the service. Two hundred friends, relatives, and parishioners gathered to bid her an earthly farewell on Sunday afternoon, September 6, 1562, in the graveyard where her husband and children were buried.

In life she had defended all who were maligned: Zwingli, Schwenckfeld, the Anabaptists, and especially her beloved husband, but that did not make her the disciple of any of them—even of Zell; she would learn from anyone but would follow only Christ. CH

By Elsie McKee

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #131 in 2019]

Elsie Anne McKee is Archibald Alexander Professor of Reformation Studies and the History of Worship at Princeton Theological Seminary and author or editor of numerous books, including Katharina Schütz Zell: The Life and Thought of a Sixteenth-Century Reformer and The Pastoral Ministry and Worship in Calvin’s Geneva. This article is adapted from her book Church Mother: The Writings of a Protestant Reformer in Sixteenth-Century Germany with the permission of the University of Chicago Press.Next articles

“Christ is the master”: Margaret Blaurer

Blaurer was of use to the church as a single woman.

Edwin Woodruff TaitDangerous pamphlets

Margarethe Prüss helped advance the radical Reformation through her publishing

Kirsi Stjerna“God my Lord is even stronger”

Exemplary women of the Reformation with confidence in their convictions

Rebecca GiselbrechtWomen of the Reformation: recommended resources

Want to learn more about lesser-known women of the Reformation? Check out these recommendations from our editors and from this issue’s authors.

the editors