BRAVE PAOLO SARPI SURVIVED SHAMELESS PLOT TO KILL HIM

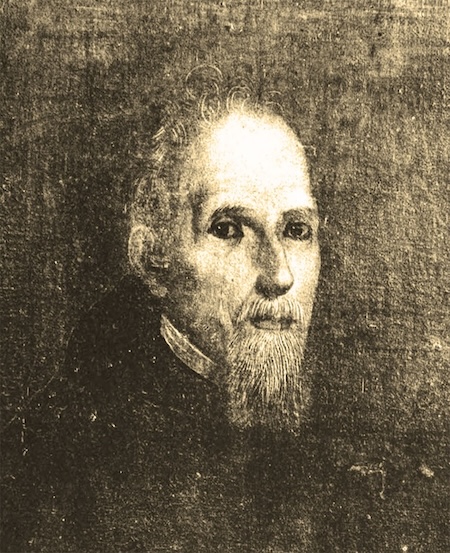

[ABOVE: Portrait thought to be of Paolo Sarpi, who was averse to having his likeness made—Alexander Robertson, Fra Paolo Sarpi, the Greatest of the Venetians. London: Sampson Low, Marston & Company, 1894. Public domain]

WHEN THE VENETIANS asked Paolo [born Pietro] Sarpi to defend their cause against Pope Paul V—who had placed their city under interdict—Sarpi requested time to study the request. A Servite friar known for his simple and holy life, he wanted to be sure he could accept the assignment with a clear conscience. Four months later he agreed.

Well-versed in canon law among a host of other subjects, Sarpi demonstrated the errors and heresies of the papal position. As part of the Venetian defense, he resurrected the arguments of Jean de Gerson, a fifteenth-century theologian who had led a French struggle against papal overreach. When Cardinal Bellarmine rejected Gerson’s reasoning, Sarpi wrote a defense of Gerson’s position.

Meanwhile, he became such a master of Venice’s state papers that he could lay his hand on any document as soon as it was needed. He indexed these so others could benefit from his immense knowledge. The rulers of Venice had complete confidence in his decisions. Highly placed individuals from many nations came to pick his brain, including Protestants, which led to a charge against him that he was in conversation with heretics.

Frustrated by Sarpi’s insurmountable defense, the pope ordered him to come to Rome. Sarpi demonstrated from canon law that the citation was illegal and refused to go. On 1 October 1607, five ruffians attacked him as he passed through the street. Although he was struck fifteen times, he emerged with only three serious wounds and survived. The assassins fled to the palace of Venice’s papal nuncio, from where they escaped to Rome. When they were not rewarded as they anticipated, they grumbled openly, leaving no doubt who had employed them to carry out the wicked deed. Later a group of cardinals attempted to poison Sarpi by the agency of a man who treated a persistent ailment of the friar. However, the plot was stymied when a letter discussing the conspiracy fell into friendly hands and its cypher was decoded. Sarpi attempted to hush up the affair so as not to bring discredit on the Church of Rome. In the end the matter could not be hidden.

The pope was finally forced to lift the interdict on Venice. This is considered the last significant attempt by Rome to interdict a major city.

When Sarpi died of old age on this day, 14 January 1623, pope Gregory XV rejoiced, saying it was God’s judgment on him. Catholics claimed he was a hypocrite because, although a practicing priest and a confessor known for his purity, he did not seem convinced of some tenets of Roman Catholic faith that had come under fire during the Reformation. For example, he did not invoke Mary during mass. He had also written a history of the Council of Trent that was not flattering to the papacy. However, the Venetians and his friends within the Servite Order lamented his loss, saying, “There will never come more among us another Friar Paul.”

—Dan Graves