Capture Of Edmund Campion, A "Diamond Of England"

APPEARANCES CAN BE DECEIVING. They can also be deadly. Edmund Campion found it so. He and his fellow Jesuits were hanged, drawn, and quartered at Tyburn because appearances were against them.

When Elizabeth ascended the English throne in 1558, she restored Protestantism to England. Pope Pius V declared her illegitimate and threatened to excommunicate any Catholic who obeyed her. Catholics plotted several times against the queen, and Elizabeth executed many. In 1581, Parliament made it an act of treason to convert English subjects to Catholicism, assuming the intent of doing so was to withdraw them from their allegiance to Elizabeth.

Several Jesuit priests entered England secretly as missionaries, to provide Communion and instruction to Catholic families, and to convert the English back to Catholicism. Among them was Campion.

Campion had been a brilliant youth. At thirteen, he was designated to recite a Latin greeting for Queen Mary when she entered London. He shone at Oxford, and Elizabeth showed him favor when she came to the throne. The important nobleman Lord Cecil called him a “diamond of England.” His prospects were bright, but Campion chose a different path. He left England and became a Jesuit, a decision of which he would later write: “The poverty of Christ has less pinching parsimony, less meanness that the emperor’s palace.”

Ordered to infiltrate England, Campion obeyed, although he knew it would probably mean his death. Because of the laws against Catholicism, he adopted the alias “Hastings,” and moved secretly from place to place. To establish his alibi in case of capture, he wrote a “Challenge to the Privy Council,” otherwise known as “Campion’s Brag.” In it he insisted that his reasons for returning to his homeland were not political. “My charge is of free cost to preach the Gospel, to minister the sacraments, to instruct the simple, to reform sinners, to confute errors; in brief, to cry alarm spiritual against foul vice and proud ignorance, wherewith many [of] my dear countrymen are abused.”

He survived under cover for a year before being betrayed. One of Elizabeth’s spies learned where Campion was staying. Government agents surrounded that house on this day, 16 July 1581. Though the owners hid Campion, he was discovered the following afternoon and captured with another priest.

Government attorneys accused Campion of treason. As evidence, they pointed to the pope’s bull against Elizabeth, subversive literature found at some Catholic homes he had visited, and his secret movements. Campion insisted he had only ministered and taught, just as he had promised to do in his “Brag.” His secrecy, he argued, was necessary because of unjust laws. He stoutly defended several other priests who were on trial with him, but the jury found all of them guilty.

Although racked, offered bribes, and tortured, Campion refused to recant. At his sentencing he said, “In condemning us you condemn all your own ancestors—all the ancient priests, bishops, and kings—all that was once the glory of England.”

—Dan Graves

----- ----- -----

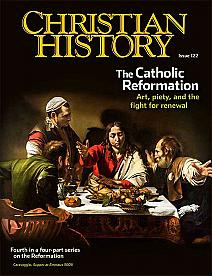

For more about the Catholic perception of the Reformation, read Christian History #122 The Catholic Reformation

Never miss an issue of Christian History. Subscribe today.