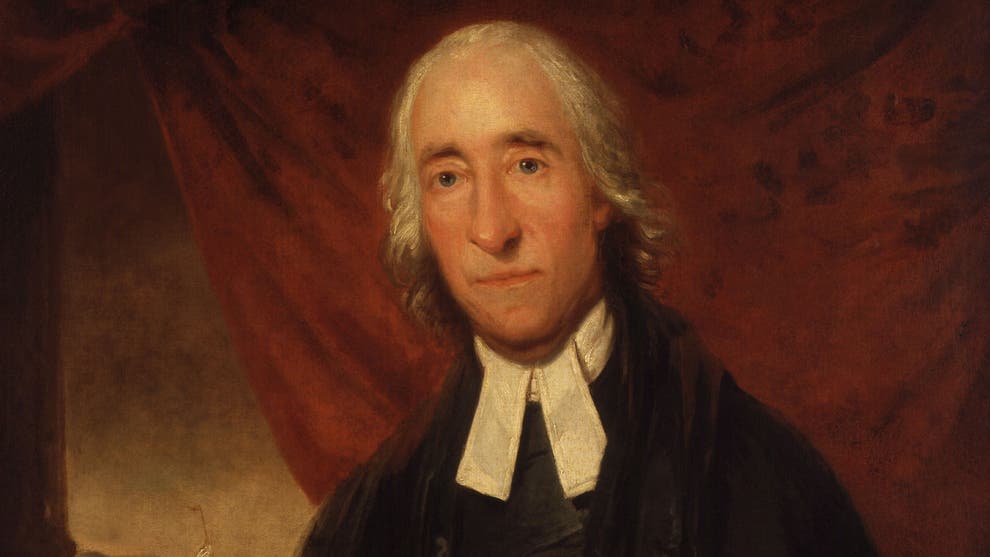

JAMES RAMSAY WAS ATTACKED FOR TELLING THE TRUTH ABOUT SLAVERY

[Above: Portrait of James Ramsay by Carl Frederik von Breda, 1789. National Portrait Gallery]

“[Y]OU OUGHT TO EXCERCISE the authority of an Editor, and reject ... unmanly poison.” On this day, 1 July 1789, The Diary or Woodfall’s Register, a London newspaper, printed a poignant letter from Rev. James Ramsay. For years Ramsay had called for abolition of slavery. West Indies planters, dependent on slaves, had slandered him in Parliament and in the press. The Diary had just printed another of those slanders. Ramsay pled that the paper not publish personal attacks:

[W]hen papers are offered for your insertion, which insidiously turn the attention of the publick from an argument of general import to particulars in a private character, you ought to exercise the authority of an Editor, and reject the being made the vehicle of the unmanly poison. I thank Heaven, my character will bear a scrutiny, as far as human judgment is concerned, equally with most men; but you cannot conceive it pleasant to be continually held up to my country as a base man, who even the Guinea Captains and Slave Tormentors may consider with contempt. I think you yourself know enough of me to believe I cannot possibly deserve it.

Ramsay’s pushback against slavery began in November 1759. He was serving in the British navy as a surgeon on the Arundel. When Arundel overtook the Swift, a slave ship in the throes of plague, James Ramsay was the only medical man brave enough to go aboard. A stench assailed his nose as he climbed on deck and grew worse as he descended into the hold. A hundred naked Africans, packed like sardines, wallowed in blood, feces, and vomit, gasping for air. He ministered what care he could and left, but the groans of the dying in the filthy, cramped, airless hold haunted him. He vowed to do something about slavery. Returning to the Arundel, he broke his thigh. A similar accident three years later convinced him he must leave the navy. Friends arranged a lucrative medical partnership for him but he turned it down. He wanted to fulfill a childhood dream and become a minister. Consequently, he became a priest of the Church of England and began work in 1762 on St. Christopher Island (St. Kitts).

His parishioners appreciated his medical skills but soon turned hostile because he opened his churches to slaves and prayed for their conversion. In protest some Whites quit attending services. To protect his family from violence, Ramsay finally had to end the public prayers.

Rich planters hated Ramsay even more when he spent his savings fighting a proposed law that would let them gouge the rest of the population with manipulative interest rates. Although he saved the island’s economy, all the thanks he got was abuse. Newspapers heaped scorn on him. His enemies tried to cut his salary. They stripped him of his role as a magistrate. One scoundrel even ranted and cursed at Ramsay from the Communion table for an hour and a half.

For nineteen years, Ramsay labored despite such hostility. When opponents said he was not fit to preach to Whites and should be sent to Blacks instead, he replied that the souls of the poorest Blacks were priceless and he would gladly preach to them. Worn down by opposition, he finally retreated to England.

Although he himself had owned slaves, his memories of cruel conditions on the plantations gave him no peace. He told friends what he had seen. Slaves were allowed only four hours of sleep a night. If one dozed off while tending sugar presses and caught a hand in the gears, the only release mechanism was an axe to chop off the entangled arm. Vicious overseers mashed slaves’ bones with sledgehammers or lay open their backs with whips. Harsh masters even burned slaves to death.

“Document these facts,” his friends begged. Once again Ramsay showed his pluck. Although he knew that the planters would come for him, he wrote An Essay on the Treatment and Conversion of Slaves in the British Sugar Colonies. This was a key publication in the campaign to abolish slavery. Others had spoken against slavery as outsiders. Ramsay spoke with first-hand knowledge.

The Essay was an immediate best-seller. But as Ramsay had expected, he drew the wrath of the planters. No lie was beneath them. During the next four years, he had to defend himself against one false charge after another. These wounded his tender spirit and his opponents knew it. A month after Ramsay protested to The Diary, he died. His leading opponent, Mr. Molineux from St. Kitts, gloated in a letter home, “Ramsay is dead—I have killed him.”

Despite Molineux and his allies, the slave trade eventually was abolished. Although Ramsay did not live to see that day, he died at peace knowing he had suffered in a righteous cause.

—Dan Graves

----- ----- -----

James Ramsay was an ally and a source for William Wilberforce. For more on the anti-slavery movement, consult Christian History #53, William Wilberforce and the Century of Reform