LI TIM OI BLAZED A UNIQUE PATH OF FAITHFUL SERVICE

[ABOVE: Old city walls of Zhaoqing, the city where Li was ordained—John Martin Perry / [CC-BY-SA 4.0] Wikimedia]

ONE DAY IN 1944, the small Anglican church in Zhaoqing,* China, was crowded. In addition to the Anglican congregation, members of a local holiness church and of an institute for the blind were also present.

The candidate for the priesthood was asked the usual questions. Among them was:

“Will you then give your faithful diligence always so to minister the Doctrine and Sacraments, and the Discipline of Christ, as the Lord hath commanded, and as this Church hath received the same, according to the Commandments of God; so that you may teach the people committed to your Cure and Charge with all diligence to keep and observe the same?”

As was expected, the candidate answered “yes” to this and other questions.

The officiating bishop, Robert Hall, and his assistant Lai Kei Chong then laid hands on the soon-to-be priest’s head. Robert Hall said, “Receive the Holy Ghost for the Office and Work of a Priest in the Church of God, now committed unto thee by the imposition of our hands....Take thou authority to preach the Word of God, and to minister the holy Sacraments in the Congregation, where thou shalt be lawfully appointed thereunto.”

Thus with forms that had ordained priests for many generations, on this day, 25 January 1944, Florence Li Tim-Oi became a priest. She was the first woman ordained to such a position in the Anglican community.

Li (her Chinese last name) was the daughter of a concubine. Although a Christian, her father saw no discrepancy in taking two wives. But whereas many Chinese had little use for female offspring, Li’s father was delighted with a girl. He named her “Much Beloved Daughter.”

Christian faith was important to Li from an early age. So was education. She acquired as much learning as she could but had to remain home while her brothers attended college. Finally, when she was 24, she talked her father into allowing her to enroll in a theological seminary. She graduated and became a deaconess in Hong Kong where she proved invaluable. At her ordination as deaconess she took the name Florence after her hero Florence Nightengale.

Following Japan’s invasion of China in 1937, Li’s bishop transferred her to Macau which had become a refugee center. Many people she knew from Hong Kong passed through the city. Soon the Japanese made it too dangerous for priests to travel to Macau to offer the sacraments. Bishop Hall authorized Li to bless and distribute the bread and wine. Eventually he decided if she was doing the job of a priest, she should be ordained as one. He invited her to meet him at Zhaoqing. Li asked the Lord to work out the details of the dangerous journey if the ordination was his will.

People helped and protected her the whole way, and she avoided Japanese checkpoints by crossing two high mountains, guided by locals who knew how to elude the invaders. Her first reaction on reaching Zhaoqing was to fall to her knees in thanks for her safe arrival.

When she made her vows, Li had already endured hunger, thirst, and threats for Christ’s sake. She had placed herself in serious danger rescuing her father from the occupiers; her vessel escaped a Japanese patrol boat only by hiding between islets during a heavy rain.

Li would suffer more at the hands of the Maoists who wrested control of China after World War II. The communists forced her into the Three Self Patriotic Movement through which they controlled churches. She was regularly denounced, forced to write self-examinations, and set to hard labor. Communist youth destroyed her Bible and other books. At one time her suffering became so acute she considered suicide but sensed that this would not please the Lord. It would give the communists grounds to say she was guilty of their accusations and bring shame on the name of Jesus.

After the Great Leap Forward and the even more terrible Cultural Revolution had passed, she was assigned to teach children. When she was old, worn out, and losing her sight, authorities allowed her to retire and gave her a small pension. Some of her family were in Canada. She obtained permission to visit them. They persuaded her to stay. After Canada granted her residency and a visa, she traveled to England for a celebration that recognized her groundbreaking role in bringing women into service at the altar.

Robert Hall took a lot of flak for his role in breaking the tradition of male-only priests but he refused to rescind his action even after the wartime emergency passed. The priesthood was a lifetime appointment, he said. He insisted that the Holy Spirit had made the decision and he had merely ratified what the Holy Spirit had already done. Decades after Li’s ordination, the Anglican Church finally, reluctantly, permitted the priestly ordination of women and eventually even authorized women bishops.

—Dan Graves

* In some transcriptions, the city is known as Xingxing.

----- ----- -----

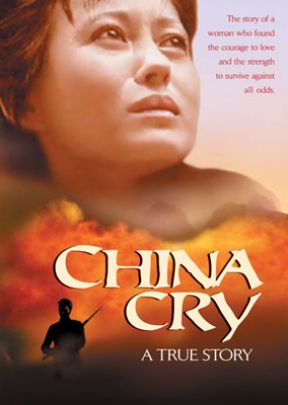

Like Li Tim Oi, Nora Lam suffered at the hands of the Chinese communists. Her story is told in China Cry

China Cry can also be streamed at RedeemTV