Instead of Unity, Marburg Brought More Division

[Above: Christian Karl August Noack (1822–1905), Colloquy of Marburg—Wikimedia]

POLITICAL AND SPIRITUAL affairs often intersect and affect each other. The Colloquy of Marburg was such an event. Reformers met in Marburg on this day, 1 October 1529, hoping to reconcile their religious differences. Philip of Hesse wanted to form a Protestant alliance to counter the powerful Catholic threat from Emperor Charles V. If Protestants could show unity on key theological issues, they would be in a stronger position than if divided.

Luther came reluctantly, under pressure from his prince, John of Saxony. His main opponent was Ulrich Zwingli. The two had exchanged harsh pamphlets over the nature of the Eucharist (the Lord’s Supper or Communion). Luther attended the meeting not to negotiate truth but to uphold beliefs and to show others their errors. Zwingli, who was desperate for allies because of the political situation in Switzerland, was more eager to forge a compromise. Several other reformers were also present, including Philipp Melanchthon and Oecolampadius.

On many issues the reformers could agree. For instance, they all accepted infant baptism and insisted that the laity should take both the bread and the wine in communion. (At the time, Catholics permitted laity to take only the bread.)

However, when the discussion (colloquy) ended on 4 October, the reformers were still far apart in their understanding of the Eucharist. Both sides wanted to honor the Bible’s words. Both wanted to uphold the statements of the Council of Chalcedon (451) in which the world-wide church set out the essential relationship of Christ’s human and divine natures. But Luther and Zwingli could not agree on how to interpret the Bible.

To Zwingli, Luther seemed to fall into the monophysite error condemned by Chalcedon (Christ's human nature is swallowed by the divine as a drop of ink in the ocean). Luther, he charged, saw Christ’s human and divine natures as functioning alike. He also accused Luther of mistaking a symbol for a physical reality. He pointed out that Jesus made many statements that we don’t take literally, such as “I am the vine,” or “I am the gate for the sheep.” A man’s body can only be in one place at a time, he said. We know that Christ’s human body is seated in heaven at the right hand of the Father. How then can it be in many loaves on earth at the same time? He quoted John 6:6 which says the flesh is powerless in spiritual matters. Therefore, he concluded, only a spiritual eating of Christ has any spiritual effect on the soul. Above all Luther should not insist we are eating a real body which had icky implications.

To Luther, however, Zwingli seemed to fall into the Nestorian error condemned at Chalcedon. (Nestorians drew distinctions between Christ’s human and divine natures that virtually split Christ into two persons.) He said Zwingli was trying to apply rationalistic and mathematical arguments to the things of God, but that God’s infinity cannot be limited that way. Many things about the incarnation we do not understand, he noted, and the Eucharist is simply one more. He accused Zwingli of applying John 6:6 to the sacrament when it has nothing to do with it. If the flesh does not avail, then why did Christ have to take on flesh and die in the flesh on our behalf? Again and again he pointed to Jesus’s words, “This is my body.”

As Andrew J. Hussman distilled Luther’s position,

One cannot deny the saving value of Christ’s present body and blood in the sacrament without also denying this same saving value in his incarnation as a whole.

At Philip of Hesse’s request, Luther wrote up articles expressing the things the reformers agreed on, including what all believed about the Eucharist. As for the rest, it was left open, with a call to Christian charity. Zwingli signed. However, he later contradicted what he signed and Luther accused him of insincerity.

At the close of Marburg, Luther refused to give the hand of Christian fellowship to Zwingli, suspecting he was a heretic. With that gesture it was obvious that the Reformation would take two paths. Switzerland would hold a rationalistic, symbolic view of Communion and the Lutherans a stance closer to medieval Catholic teaching. As for the Catholic Church, it condemned both approaches at the Council of Trent (1545–1563).

—Dan Graves

----- ----- -----

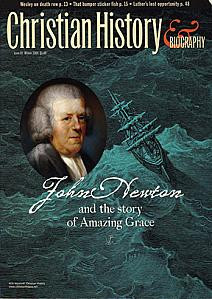

For another view of Marburg, read "Turning Point: Luther’s Lost Opportunity" in Christian History #81, John Newton: Author of “Amazing Grace”