Toyohiko Kagawa Lived in a Slum to Rescue Japanese for Christ

TOYOHIKO KAGAWA, who became one of Japan’s most famous Christians, was born on this day, 10 July 1888, as the son of a concubine. His father died soon after his birth and a rich uncle took him in. As a teenager, he was eager for foreign knowledge and sought the acquaintance of a Presbyterian missionary, H. W. Myers, who eventually baptized him. When Kagawa announced he wanted to become a Christian minister, his uncle threw him out. So the boy worked as a servant while completing school. He took his theological training at Kobe Presbyterian Seminary and at Princeton University.

While still a young man, Kagawa suffered from tuberculosis. Hoping for a cure, he lived with peasants on a seashore. There he observed how each home was affected and made miserable by its secret sins. He based a novel on the experience: Across the Death Line. Unable to sell it, he laid it aside.

Having seen the dark side of his country’s culture, he determined to move to the slums where he might do Christian work among thieves, murderers, and prostitutes. His friends implored him not to waste his life. In the Japanese slums, ten people would share a couple of mats. There was no privacy and no hygiene. Still suffering from tuberculosis, he would no doubt die in the slums. Kagawa, however, would not hear their pleas. Amazingly, he recovered his health.

Living on $1.50 a month, he labored among the outcasts of society, putting his faith into action. He organized labor societies and peasant unions. “I am a socialist because I am a Christian,” he said. His activism, combined with the growing threat of Communism, convinced the government to renovate the slums.

Because of his work, Kagawa’s name became well known. Mission magazines frequently mentioned him. He wrote pamphlets, poems, and books. Typical of his short poems is this:

I came to bring

God to the slum;

But I am dumb,

Dismayed;

Betrayed

By those

Whom I would aid;

Pressed down,

So sad

I fear

That I am mad.

Several years after he began his slum work, Kagawa dusted off his neglected novel. This time it found a publisher. It quickly became a Japanese bestseller. Several people, including the great-grandson of Prince Iwakura (architect of the Meiji Restoration) became Christians through reading it.

Kagawa spent the royalties from this novel (revised as Before the Dawn) and a second best-selling novel, Shooting at the Sun, on relief for the poor. For Kagawa, the cross was the power of the love of Christ and of suffering for righteousness’ sake. When he married, his wife and children shared his poverty.

This minister to the poorest of the poor died in 1960. Japan’s Emperor posthumously awarded him the nation’s highest honor, the Order of the Sacred Treasure.

—Dan Graves

----- ----- -----

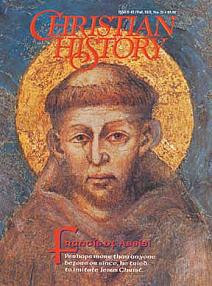

In his willingness to embrace poverty, Kagawa was not unlike Francis of Assisi, Christian History #42

Never miss an issue, subscribe now.