Judsons Found a Cheerless Home in Rangoon

“THE PROSPECT OF RANGOON as we approached was quite disheartening. I went on shore just at night, to take a view of the place, and the mission house; but so dark, and cheerless, and unpromising did all things appear, that the evening of that day, after my return to the ship, we have marked as the most gloomy and distressing that we ever passed.” That is how Adoniram Judson described his arrival in Burma on this day, 13 July 1813.

Rangoon was “a miserable, dirty town” built on a swamp in one of the outlets of the Irrawaddy River. All the sewage of the city—and the smell—accumulated in the channels of the river until tides moved it out to sea. The vegetation was beautiful, but the people went hungry because they had no incentive to grow much. The government seized whatever they produced. Food was costly. At the very least, the Judsons had a home— an earlier missionary, who had abandoned the work in Rangoon, turned his house over to them.

Such an arrival could only be a matter of wild chance—or of God’s extraordinary providence. The Judsons had fled Calcutta because the East India Company was prepared to deport them to England. Escaping, they made their way first to a French island and then to Madras. Learning that the East India Company had attempted to send fellow missionaries to England as spies (the United States and Britain were at war), the Judsons determined to leave India at once. The only ship they could get was bound for Burma. They boarded the Giorgianna, which Judson described as “a crazy old vessel.”

Judson had hired a Portuguese woman to accompany his wife, Ann. This maid dropped dead the day they boarded the ship, and the shock of the incident weakened Ann’s health considerably. Their vessel sailed into a typhoon and Ann almost died. But by God’s mercy, she did not, and the credit for evangelizing Burma was as much hers as Adoniram’s. She proved a better linguist than he, which greatly assisted his efforts to learn the language and translate the Bible. It was five years before the pair baptized their first convert. By then, other missionaries had joined them.

In 1824, Britain went to war with Burma and Judson was arrested. Burma’s king made no distinction between Americans and British, as long as they were white. Ann labored to free her husband and provide him the bare necessities of life. But in that hot climate, she sickened. The British defeated the Burmese and after twenty-one months, Judson was released. Joy turned to sorrow when Ann and their young daughter, Maria, died soon after.

Adoniram’s own death came in 1850 at sea, but the Judsons’ lifelong labor had not been in vain. By then, there were seven thousand Burmese Christians.

—Dan Graves

----- ------ ------

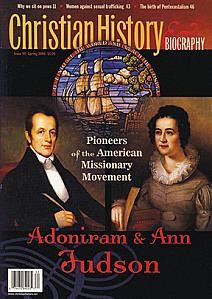

For more on the Judsons, see Christian History #90 Adoniram & Ann Judson: American Mission Pioneers

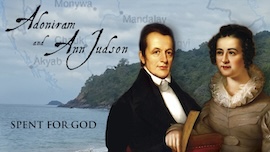

Watch at RedeemTV Spent for God and The Torchlighters, Adoniram and Anne Judson Story .

Adoniram and Ann Judson: Spent For God and Torchlighters: Adoniram and Ann Judson can be purchased at Vision Video.