Las Casas Fought to Protect Indians from Spanish Colonists

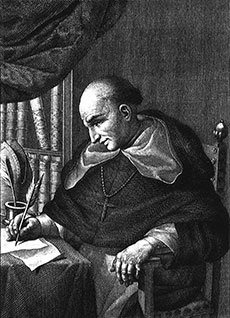

[ABOVE: Enguidanos, Fray Bartholomew de Las Casas—Francis Augustus MacNutt, Bartholomew de las Casas; his life, his apostolate, and his writings. Putnam, 1909. Public domain]

WHEN THE INDIANS of central America learned of the death of Bartolomé de las Casas on this day, 31 July 1566, they mourned and lit fires in his name. Las Casas had been a true friend to them. They called him “Father to the Indians.”

From their arrival in the New World, the Spanish had treated the native population with great cruelty. Las Casas initially participated in raids on the Indians. He had migrated to Santo Domingo in 1502, and settled on a plantation (encomienda) there, enjoying the fruits of conscripted labor. His attitude shifted gradually, due in part to Dominican friars, arriving in 1510, who denounced the cruelty of the Spaniards. That same year, Las Casas became the first Spaniard ordained in the New World. In 1511, Father Montesinos, another Dominican, asked the colonists how they could call themselves Christians while perpetrating their daily barbarities. Montesinos’s audience screamed threats at him.

Despite becoming a priest, Las Casas remained a plantation owner. He was a chaplain to the Spaniards who conquered Cuba in 1513. But the following year, while reading the Bible, he became convinced the Spanish had been wrong to seize native lands and treat the inhabitants with such barbarity. He freed his slaves and preached that all slave-owners should do the same. When his counsel was rebuffed, he sailed to Spain with Montesinos and another friend to lay his case before the king.

He reminded the king that the pope had granted Spain its New World possessions with the stipulation they evangelize the Indians. Cardinal Cisneros, acting as regent, appointed Las Casas Protector of the Indians and sent a commission of three Hieronymite friars (members of an Augustinian religious order) to assume the government of the New World with Las Casas as their advisor. The plantation owners and governors resisted the commission so fiercely that it accomplished little. Relations between Las Casas and the commissioners deteriorated.

For fifty years, Las Casas worked in behalf of the Indians. He involved himself in a number of social (and socialist) schemes for their well being, which, for the most part, came to little. He attempted to evangelize Guatemala, preaching the Gospel to his hearers as equals, insisting that conversion must be voluntary and based on a knowledge and understanding of the faith. This went against the methods of the Franciscans who held mass baptisms of uninstructed people.

Returning to Spain, Las Casas succeeded in having the New Laws of 1542 promulgated. These were fairer to the Indians, but were largely disregarded by the Spaniards, who knew the king was too far away to enforce them. Altogether, Las Casas returned to Spain five times to lobby for the Indians. His last voyage was in 1546, after he was appointed bishop of the impoverished Chiapas region of Mexico. Because he refused absolution to slave owners, even those who were dying, unless they freed their slaves and restored their property, Las Casas faced furious opposition from the Spaniards.

Eventually, the Indians rose up in revolt against Spain’s cruelty. Seizing the opportunity, enemies of Las Casas blamed his teaching. The Spanish Court ordered him home to answer accusations. He proved it was Spanish cruelty that led to the revolt, and the king believed him. Nonetheless, he was not allowed to return to his see. He died in Spain in 1566. A few days before his death, he wrote a last letter against the injustice done the Indians: “It has brought great infamy on the name of Jesus Christ and of the Christian religion, entirely hindering the spread of the faith and irreparably injuring the souls and bodies of those innocent peoples.”

—Dan Graves

----- ----- -----

Las Casas is among many fascinating figures mentioned in Christian History #130 Latin American Christianity: Colorful, complex, conflicted

Don't miss an issue, subscribe now.