Cholera Almost Cut off the Gospel of Charles Finney

IN 1821 a law student named Charles Finney went into a woods in New York, vowing, “I will give my heart to God or I will never come down from there.” Christians in his town had been praying for his salvation. Although a singer in the Presbyterian choir, he had never made peace with Christ. In the woods, he found he was not able to get right with God until he confessed his sins aloud. All the while, he was terrified that someone might overhear him. When he had made a clean confession, he felt God’s love flow through his body.

The next morning, after a deep struggle, Finney gave up his law career. He was certain God was telling him to preach the gospel. Convinced that Christians were wrong in the way they went about winning souls, he emphasized intensive preparatory prayer, confidence that results would follow, direct calls to listeners to repent, daily revival meetings, and “anxious benches” where those struggling could wrestle with God. All of these became standard revival techniques. Close to half a million people confessed Christ in his meetings, although many did not live up to their profession. He was even successful in winning converts in the so-called “burned out district” of the Northeastern United States, where so many earlier awakenings had passed through that the inhabitants were later said to have become numb to gospel appeals.

Because of his insistence that people could get right if they chose to, Finney was accused of being a Pelagian. He also taught the belief that Christians can become sinless here and now to the extent of their knowledge, and emphasized a moral theory of the atonement, focusing on the influence Christ’s example has over his followers rather than on Christ’s substitutionary death. Finney wrote his Systematic Theology to explain his views. In places it reads like a treatise on the American system of government.

In 1832, Finney left his itinerant evangelism and accepted a call to the Chatham Street Church in New York. He was supposed to be installed as its pastor on this day, 28 September 1832. However, he became seriously ill in the middle of the service. Soon it was clear he had cholera, a disease with diarrhea and severe dehydration. Others who contracted the disease the day he did died. His life hung in doubt for several days, but he lived, although so weakened it would be months before he could take up his full duties again.

Finney was no less innovative as a pastor than he had been as a revivalist. He allowed women to pray aloud in his services and insisted that every convert must demonstrate a changed life by tackling the ills of society. Consequently, the Chatham Street Church operated many benevolent and charitable works. He taught that Christians would usher in Christ’s thousand-year rule on the earth, and thus that Christian works would hasten the day of Christ’s return.

Finney’s support of women’s rights and his opposition to slavery led him to insist that Oberlin College, with which he was closely associated, admit blacks and women on an equal footing with whites and men. Oberlin became the first American college to graduate a black woman with a B.A.

Finney died in 1875, having lived forty-three years after his brush with cholera.

—Dan Graves

-------------

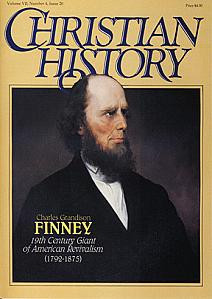

For more about Charles Finney and his successful ministry, read issue 20 of Christian History, Charles Grandison Finney: 19th-century giant of American revivalism.