John Craig Walked to Church with a Musket on His Shoulder

JOHN CRAIG was born in Ireland. His parents sent him to be educated for the Presbyterian ministry in Edinburgh (Scotland). Craig, however, wanted to be a doctor. He pretended he was studying for the ministry while covertly taking medical classes. When he contracted a severe infection and expected to die, his conscience tormented him. He promised God obedience. Although sick for six months, he recovered and kept his word.

In 1734, he sailed for America but almost did not make it. During a violent storm, a wave swept him overboard. Amazingly, the next wave flung him against the side of the ship where he was able to grab onto some “holds” and pull himself back onto the deck.

Afraid of the responsibility of leading a congregation, Craig taught school and did evangelistic work for six years before accepting a call to western Virginia. On this day, 3 September 1740, he was installed as Presbyterian minister to Scots-Irish in the Shenandoah, charged with an area of about six hundred square miles.

The Presbyterians built two “meeting houses,” called this because calling them churches would place them in competition with the Church of England, Virginia’s official religion.

Each meeting place was about six miles from Craig’s farm. He walked to church and allowed his children to laugh and play along the way, much to the disapproval of some of his congregation.

Regardless, John Craig worked hard among his people, even though they sometimes failed to pay him. He found his poorer church to be friendlier, more receptive to the gospel, and more faithful with his salary than the rich congregation at Tinkling Spring. Craig had argued strongly against the building at Tinkling Spring and swore that none of the spring’s water would ever tinkle down his throat. It was a promise he firmly kept, no doubt to his own inconvenience.

From 1740 until his death in 1774, he preached, baptized, and raised cattle and horses in the Shenandoah. He also established churches and ordained elders in neighboring regions. When asked how he found so many suitable men around New River and Holson, he replied, “Where I cudna get hewn stanes, I tuk dornacks” (Where I could not get hewn stones, I took pebbles.)

During the French and Indian war, he advised his people not to flee, saying it would shame Virginia and disgrace their faith. He spent a third of his own resources building forts in the Shenandoah, and walked to church with a rifle in hand and powder horn over his shoulder.

In his last sermon at Tinkling Spring, he implored the congregants to consider their sins of “self conceit, pride, vanity, hypocrisy, wickedness, and folly,” and listen to his advice as a sincere friend and pastor. “How can I leave you at a distance from Christ, strangers to the God that made you? I cannot leave you till I give you another offer of Christ and the covenant of grace.”

—Dan Graves

----- ----- -----

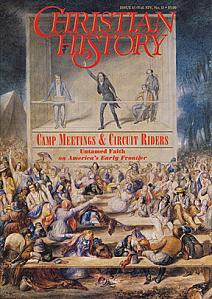

For more background on frontier Christianity, look at Christian History #45 Camp Meetings & Circuit Riders