Eternal views

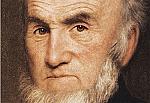

[ABOVE—John Everett Millais, Portrait of Cardinal Newman (1801–1890) (oil on canvas, 1881)—Bridgeman Images]

What is the point of a university? What do students gain from a liberal arts education? John Henry Newman had pointed words about those controversial questions in the 1800s. “One of the chief evils of the day,” he wrote in his 1852 preface to The Idea of a University, is the idea that “an intellectual man, as the world now conceives him, is one who is full of ‘views’ on all subjects of philosophy, on all matters of the day.” (Today, we might call this a “hot take.”) Against this “viewiness,” Newman proposed in his famous book “a philosophical habit of mind,” or a rightly ordered intellect: formed by a liberal education, attuned to theological truth, conscious of the achievements and limits of the various sciences and methods.

The Idea began as a series of lectures to an audience in Dublin in 1852, shortly after church officials invited Newman to be the founder and rector of a new Catholic university in Ireland. This Catholic University of Ireland was the Irish Catholic hierarchy’s response to the 1845 establishment of the intentionally secular Queen’s University of Ireland, which imposed no religious test for admission and offered no religious instruction of any kind.

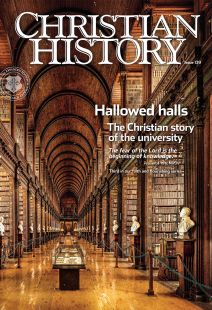

Throughout the nineteenth century, old universities such as Oxford opened their doors to non-Anglicans, and new universities such as University College London (see p. 32) were founded on explicitly secular and utilitarian premises. From the root of these dueling views of university education grew the questions: What to do with theology? Is it a branch of knowledge, the subject of a science, and therefore worthy of inclusion in a university curriculum? Or is it simply a taste, a matter of opinion, a mere sentiment that disrupts the smooth work of research and development?

A circle of science

In response to these debates, Idea simultaneously addressed three audiences. First, it aimed to convince the Irish hierarchy that a university and a liberal education are goods in themselves. Newman needed the bishops to understand that he would not head a mere seminary. Second, Newman rebutted the view that theology should be excluded from university education. Third, he confronted utilitarian arguments that the old model of liberal arts education, now useless, ought to be replaced by educating students in more practical ways.

The Idea first laid out a vision of the whole “circle of sciences, [where] one [science] corrects another.” Theology enters this circle both as one science among many and as the ground holding all the sciences together. But adjudicating between one science and another is the province of “philosophical or liberal education.” This formed the Idea’s second concern: the influence of the sciences and a collegiate atmosphere on the individual mind. An education can only be truly liberal if it occurs amid other people pursuing similar ends.

Newman believed the mission of a university is not to advance knowledge or facilitate research; the university exists to cultivate intellectual virtues within its students and professors—men and women who perceive the interconnection of all knowledge because they understand the world itself to be created.

By Austin Walker

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #139 in 2021]

Austin Walker, assistant director, The Lumen Christi InstituteNext articles

Delicate balance

Fundamentalist heritage and the evangelical mind at Wheaton College

George M. MarsdenSeeking and teaching virtue

Christian bearers of the liberal arts tradition from the Middle Ages to the present

Jennifer A. Boardman