A bishop’s work is never done

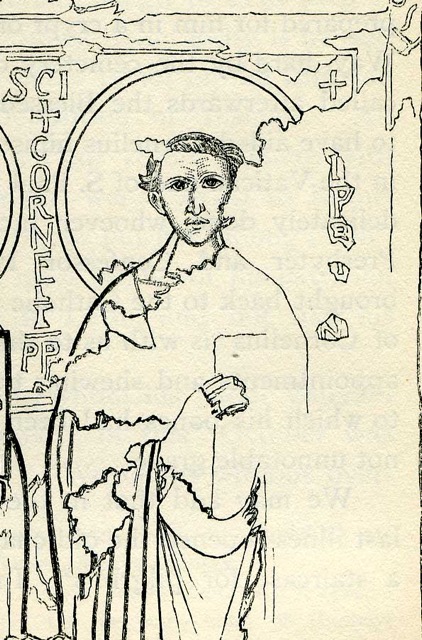

[Cyprian]

IN AD 249 ROMANS THOUGHT a thousand years had passed since their empire’s legendary founding. People feared this millennium would bring calamity: when everyone made it through alive, Emperor Decius (who had usurped power in December 249) ordered a sacrifice on January 3, 250, aimed at restoring Rome’s “golden age.” Everyone except Jews (exempt by law) had to sacrifice to the gods in the presence of a Roman official and get a certificate. When Christians refused, one of the most famous eras of persecution began.

Hiding in the hills during the Decian persecution, bishop of Carthage Cyprian (c. 200–258) wrote letters to his flock to counter mass apostasy. He was largely unsuccessful; many sacrificed or obtained false certificates, causing profound pastoral repercussions.

From bishop to bishop

Upon his conversion from an elite pagan background to Christianity around 246, Cyprian had given away almost all his wealth for the relief of the poor. Just two years later, the young Christian was elected bishop of Carthage (in modern Tunisia). For 10 years as bishop, he carried his people through wave after wave of crisis: political, socioeconomic, natural, and ecclesiastical. After a brief lull (and a terrible plague), Emperor Valerian launched another wave of persecution in 257. This time Cyprian was captured and martyred. Supposedly his only words before his execution were “Thanks be to God!”

How different was the episcopal tenure of Basil of Caesarea (330–379). History bestowed on him the rare honorific “the Great”—and he certainly did much to earn it. Despite beginning amid persecution, his Christian life and ministry took a very different path. Basil was born of an aristocratic Christian family in Cappadocia (modern central Turkey) prominent for piety, wealth, and social status. After his baptism, like Cyprian, he sold his possessions, distributed the proceeds to the poor (citing Matthew 19:21), and founded communal monastic communities across Cappadocia.

But now Christianity was legal, so Basil could focus his main energy on public efforts. Ordained bishop of Caesarea and metropolitan bishop of Cappadocia in 370, he proved a skillful church administrator, dealing with political and ecclesiastical negotiations. He could also fully exercise his gifts as an astute theologian, a powerful preacher, and an effective social activist on behalf of the poor. By 372 he had built his famous complex just outside Caesarea—the “Basileiad”—considered by many the world’s first hospital. Gregory of Nazianzus said it outshone the Great Wonders of the ancient world. Like Cyprian Basil died relatively young, but his was a natural death around age 50 from liver disease.

These two bishops’ stories show how Christians changed their interactions with their non-Christian neighbors through time and how their bishops led them in doing so. The Christian population grew at an amazing rate, from about 2 percent of the empire at the time of Cyprian (250) to about 12 percent at the time of Constantine’s Edict of Milan (313). Growth centered in the Greek-speaking eastern part of the empire. By the mid-fourth century, Christians exceeded a majority of the empire’s population (56 percent).

At first Christians and pagans (upholders of the traditional Greco-Roman and Mediterranean gods and customs) met on a daily basis. However at times those neighborly relationships turned to misunderstandings and accusations about Christian beliefs and practices. The pagans’ fear that the Christians had incurred the traditional gods’ wrath by abandoning them sometimes led to violent acts.

They may have been in the minority, but the first Christians were a busy group. They quickly set about laying the groundwork for growth, led by their bishops. As the chief pastor of his locality, the bishop served and led his people in three main roles. First he oversaw the celebration of the Eucharist and baptism. Second he preached and taught the true doctrine to guard the apostolic tradition from heresies. And third he supervised the community’s works of mercy to their poor, their sick, and their widows and orphans (see “Healing the city,” pp. 17–20).

Order Christian History #124: Faith in the City in print.

Order Christian History #124: Faith in the City in print.

Subscribe now to get future print issues in your mailbox (donation requested but not required).

In fulfilling these duties, bishops defined acceptable boundaries between Christians and non-Christians and helped organize communal Christian identity around shared theology and practices. The bishop expected the congregation and other clergy (priests and deacons) to obey and support him and his office, especially in the times of crisis (such as false teachings, schisms, and persecutions). Cyprian, for example, functioned during one of the most challenging crises of the Carthage church, already a formidable social and economic institution with a massive charitable operation. As a result, he enhanced the bishop’s authority in light of a controversy over the reconciliation of those who had lapsed during persecution. He taught that only the bishop—not priests or “confessors” (those who had held up under persecution)—could oversee the penance of the lapsed.

From persecuted to powerful

As Christianity changed its status from a persecuted superstition to the favored religion of emperors, unprecedented imperial resources and support ensued. And as the empire was increasingly “Christianized,” interactions between pagans and Christians changed. In the Constantinian era, the bishops gained new power and responsibilities—political, institutional, and economic—not only in the Christian community but also in Roman society as a whole.

Constantine restored church properties along with religious freedom. Then he took things a step further. Churches and bishops were exempted from compulsory public service and taxes and were given a financial subsidy and sometimes land. As Eusebius put it, Constantine provided the church with “the abundance of good things.” He even granted bishops the final judicial authority in civil suits, especially on behalf of the poor, and his successors gave bishops the unusual privilege of manumitting slaves in the church.

As Constantine made the church officially visible, he also made it accountable to the public for these very public gifts. Up to this point, the church had received offerings from the faithful, especially the “middle class” and the wealthy, primarily to care for its own poor. Now traditional Christian charity came to be regarded as a service to the public.

Not just Christians but also non-Christians now identified the church closely with its care of the poor in Roman cities. Theodosius’s code of laws stated, “The rich must assume the secular obligations and the poor must be supported by the wealth of the churches.” The church thus acted as a mediator between the rich and the poor, and bishops emerged as “lovers of the poor” and “governors of the poor” in their public role.

Old habits die hard

For a while elite pagan senators lived in relative harmony with Christianizing emperors and bishops as Christianity gradually infiltrated Roman society. The inclusion of pagan imagery in Christian catacombs such as the Via Latina indicates the fluidity of ideas and the reality of coexistence in upper-class society. The Christian Council of Elvira in Spain (c. 305) banned sharing fine clothing with pagan neighbors and attending public sacrifices, showing that Christians of a certain status were interacting more comfortably with pagan neighbors than bishops found acceptable.

In fact some ordinary folks protected their houses against sudden disaster through the practice of both pagan and Christian rituals. Even at the turn of the fifth century, many Christians would have agreed with a member of Augustine’s congregation in North Africa: “To be sure, I visit the idols, I consult magicians and soothsayers, but I do not forsake the church of God.

I am a Catholic Christian.”

But increasingly Christians focused suspicion and hostility on large urban temples to pagan gods. For instance, at Aegeae (a city in southern Turkey), the great temple of Asclepius, a popular healing god, was razed in 331 and its columns either removed or reused in the Christian church on the site. Pagans viewed this as an outrage and an insult to the many thousands who had flocked there in search of healing.

The great temple of Serapis of Alexandria was also destroyed in 391, and a nearby shrine of Isis (a popular Egyptian goddess) converted around the same time into the church of St. John the Evangelist. Worshipers of Isis nevertheless continued to visit to receive healing and consult the oracle. In response the bishop of Alexandria fostered devotion to Christian miracle healers Saints Cyrus and John, placing their shrine opposite that of Isis.

Basil of Caesarea was concerned about Christians lapsing into pagan cults. Sacrifices to pagan gods put Christians at risk of apostasy—offenders could be readmitted to the sacrament only at the point of death. Such severe penalties suggest an attempt to stamp out participation in sacrifices by baptized Christians wishing to blend in; they might do so as members of civic communities during pagan festivals, public and private.

At times Basil had to minister to divided aristocratic families when one of their children accepted Christian baptism. So he wrote to the pagan Harmatius: “Since [your son] has preferred the God of us Christians, that is the true God, before the gods of your people, which are numerous and are worshiped through material symbols, do not be angry with him but admire instead his nobility of soul.”

Eating with Jews

The Christian relationship to Judaism was also changing. Christians had always defined their identities in contrast to Jewish beliefs and practices. As Romans began noticing the difference between Christians and Jews in the second century, the two faiths developed polemics against each other. Under Constantine and after, as church leaders gained political power, they used it to aid and pressure emperors to suppress Judaism.

John Chrysostom (c. 349–407) served as bishop of Constantinople in the early fifth century, but he wrote Against Judaizing Christians when he was a celebrated preacher and priest at Antioch (386). The Jewish community there was vibrant; apparently there were enough Jewish-Christian interactions to cause concern, and some Christians found Jewish rites irresistible. Chrysostom warned Christians against participating in Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, as well as observing the Jewish Sabbath. His harsh language shows the extent to which he feared Judaism’s power of attraction.

Around the same time in an infamous letter to Emperor Theodosius I (347–395), Ambrose of Milan (c. 340–397) opposed the emperor’s decision to punish Christians responsible for burning down a synagogue in Callinicum, a town on the Euphrates. To enhance his case, Ambrose listed cities where Jews had burned churches—Gaza, Ascalon, Beirut, and Alexandria—and pointed out Jewish “acts of calumny” against Christians. Although Theodosius reaffirmed in legal documents the right of Jews to meet unhindered in their synagogues, Ambrose’s opposition reflected a growing mood among Christians.

As both the legal and social situations of Jews seriously deteriorated in the late fourth century, sometimes with the unfortunate support of Christian mobs, church councils discouraged social interaction between Jews and Christians. The Council of Elvira prohibited intermarriage; the Council of Vannes (461) strongly limited Christian interaction with Jews by stating that it was “shameful and sacrilegious for Christians to eat [the Jews’] food.” Laws and sentiments against Jews would outlast the empire itself, with repercussions echoing to the Crusades and beyond.

What makes a good bishop?

In the late fourth century, Augustine (354–430), the man whose name is perhaps more synonymous with Western theology than any other, had become first a convert, then a priest, then a bishop. In his famous comparison of earthly and heavenly cities, The City of God, he noted, “No man can be a good bishop if he loves his title but not his task.” Amid all these controversies and crises, bishops at their best exercised their authority as passionate advocates and statesmen to protect their flocks, their communities, and their cities. CH

This article is from Christian History magazine #124 Faith in the City. Read it in context here!

By Helen Rhee

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #124 in 2017]

Helen Rhee is professor of church history at Westmont College and the author of several books on wealth, poverty, and early Christianity.Next articles

“An expanding circle of love and justice”

We spoke to Katelyn Beaty, editor at large for Christianity Today, on how Christians today interact with their non-Christian neighbors.

Katelyn Beaty and the editorsHealing the city

How Christians helped the sick and poor in the Roman Empire’s cities

Gary B. Ferngren“The only stumbling block is the cross”

We spoke to Doug Banister, the pastor of All Souls Church in Knoxville, Tennessee, about how his church does urban ministry.

Doug Banister and the editorsChristian History timeline: the tumultuous life of early urban Christianity

The Christian History timeline for the early church in Roman cities

the editors