A motley, fiery crew

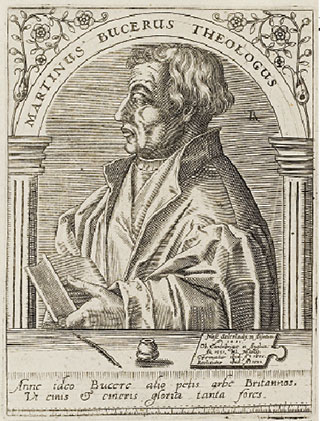

MARTIN BUCER (1491–1551)

Next to Luther and Melancthon, Bucer was the most important leader of Protestantism in Germany, and in his own time one of the most influential religious figures on the continent. He was instrumental in bringing Luther and Zwingli together for their fateful confrontation at Marburg, a leader in colloquies between Protestants and Roman Catholics, and generally spoke for moderate Protestants in Europe, who sought ecumenical solutions in a time of confessional conflict.

Though his father was only a poor cobbler, Bucer received an excellent education and at 15 entered a Dominican cloister. In 1518 Bucer was captivated

by Luther’s thought and sprang to his defense though a member of indulgence-seller Tetzel’s order. His ecclesiastical superiors took a dim view of his

new enthusiasm; Bucer left the Dominicans and became a parish priest in Landstuhl (where he married a former nun, Elisabeth Silbereisen). Then he moved to Weissenburg, where, caught in a sticky political situation, he had to slip out under cover of darkness. Finally landing in Strasbourg, he swiftly moved to the leadership of the reform movement, serving as a pastor from 1524 to 1540.

Bucer’s writings abound with rich descriptions of the work of the Holy Spirit in the life of the church. He wrote a new liturgy for worship a year before Luther composed the German Mass, issued three catechisms, introduced the office of lay presbyter, reinstituted confirmation to further more rigorous Christian education, persuaded the town council to abolish the Mass, and helped establish a preparatory school and seminary. Unable to implement a vigorous program of overall discipline for the well-being of the church, in desperation he suggested organizing groups of people willing to submit to strict discipline on a voluntary basis.

In 1548 Charles V issued the Augsburg Interim, a document favorable to Catholic teachings and practices. Though it permitted Protestant ministers to marry and allowed Communion in bread and wine, Bucer found it unacceptable. When Thomas Cranmer invited him to England, he readily accepted. There he lectured at the University of Cambridge, assisted Cranmer in revising the Book of Common Prayer, and as a present for King Edward VI composed his most famous treatise, De Regno Christi. The king was delighted, and the University of Cambridge awarded Bucer a doctorate. But he soon became seriously ill and died, buried far from home.

HANS DENCK (c. 1500–1527)

Hans Denck, by training a humanist and by occupation a schoolmaster, studied at the University of Basel under Oecolampadius (see below) and also took a job as proofreader and editor in a printing firm. After his graduation in 1519, he wandered throughout south Germany: when Oecolampadius nominated him to be principal of a Nuremberg school in 1523, it seemed a godsend to be able to settle down. Alas, it was not to be. Caught in religious crossfire, he soon had to resign, banished from the city forever in 1525.

Order Christian History #118: The People’s Reformation in print.

Subscribe now to get future print issues in your mailbox (donation requested but not required).

By June of that year, he could be found in the home of an Anabaptist in St. Gall, but was soon on the move again to Augsburg. There he met Balthasar Hubmaier (see below) who persuaded him that the Anabaptist understanding of believer’s baptism was the correct view. Denck taught this view to Hans Hut (c. 1490–1527), who would go on to found the Hutterites; but he himself eventually fled (pursued by various groundless rumors) to Strasbourg. He was there barely long enough to debate Bucer and Anabaptist Michael Sattler before it was on to Worms, Basel, Zurich, back to Augsburg, and finally back to Basel in 1527, where Oecolampadius forced him to recant his views as a condition of remaining. He did so, in a modest document that represented no important change in his positions, promptly contracted the plague, and died.

For Luther, the Word always came from outside, through preaching and sacraments. For Denck, this tied God down to external means and implied that God does not want everyone to be saved, since not everyone has access to preaching and sacraments. Denck believed that the Word of God is an inner voice calling men and women to obedience: while millions of people have not read the Bible and cannot hear the proclamation of the Gospel, everyone has heard the voice of God speaking within. The Gospel is the summons to imitate Christ, Denck thought, and authentic faith is obedience to that summons, wherever it takes you. It took him many places indeed.

BALTHASAR HUBMAIER (c. 1485–1528)

Preacher and martyr Hubmaier studied as a young man with Johannes Eck, later Luther’s famed opponent. Eck thought highly of him and arranged for Hubmaier to follow him to the University of Ingolstadt. But he resigned his post in 1516 to become a preacher in Regensburg. There he became involved in a controversy with the Jews, led a movement agitating for their expulsion, destroyed their synagogue, and erected in its place a chapel dedicated to Mary. Claiming that miracles had occurred in the new shrine, he submitted a list of 54 to the city council. Eventually they made him leave town.

In 1523 he publicly took sides with Zwingli but was soon convinced by the arguments of Conrad Grebel and the early Anabaptists. On April 15, 1525, he submitted to rebaptism, and on Easter Sunday, April 16, 1525, he baptized 300 adults in the parish church at Waldshut, using water from a milk pail rather than the baptismal font.

Hubmaier was in general sympathy with the Peasants’ War, and the Austrian government regarded him as one of the leaders of the rebellion, though he was less concerned with peasant rights than with the freedom of Waldshut to remain Protestant. He escaped the government’s clutches in 1525 and fled to Moravia, but the Austrians came after him.

Moravian nobility would have resisted extradition on charges of heresy but did not want to risk their lives to protect someone charged with treason. Hubmaier was returned to Vienna, where he was tortured and burned at the stake on March 10, 1528. Three days after his execution, the same authorities who condemned Hubmaier drowned his wife in the Danube.

ANDREAS VON KARLSTADT (1480–1541)

Karlstadt, Luther’s onetime colleague at the University of Wittenberg, rejected infant baptism, but was not really an Anabaptist; he appropriated mystical terminology and ideas from the later Middle Ages but reconciled them with the insights of the Lutheran Reformation. Driven by Luther to study Augustine, he became more of an Augustinian than Luther was. Luther charged him with being a legalist and obscuring Christian freedom, but he also had a spiritualist streak.

Luther and Karlstadt clashed for the first time at a disputation held in 1516, which led Karlstadt to buy a complete set of Augustine’s works and fill in the gaps in his theological education. He soon became Luther’s ally in the controversy over indulgences that was sweeping Europe, and he composed 380 theses against Johannes Eck. Eck challenged him to a debate in Leipzig, hoping to draw Luther into the discussion.

The Leipzig Disputation was not a great success for Karlstadt. The cart in which he traveled unceremoniously dumped him on the ground at the city gate; a physician bled him twice (a common sixteenth-century medical treatment), but he was shaken and not in his best form. He tried to support his argument by reading lengthy quotations from the church fathers, which he needed Melancthon’s help to locate. Eck, who had a prodigious memory, ridiculed him and succeeded in getting a rule passed against the use of reference books. Generally Eck treated Karlstadt like a sparring partner in a preliminary bout, rather than a serious contender for the title in the main event. Karlstadt returned home to write a vitriolic attack on him, Against the Dumb Ass and Stupid Little Doctor. Eck promptly added Karlstadt’s name to the papal bull against Luther.

While Luther was in hiding at Wartburg Castle, Karlstadt went to Denmark to establish the Reformation but beat a hasty retreat after only six weeks. His colleagues had scarcely begun to miss him when he reappeared, frustrated and a little out of breath.

In December 1521 Karlstadt announced his intention to marry Anna von Mochau, 25 years his junior. Then on Christmas Day, after having been expressly told not to, he gave both bread and wine to the laity in Communion—celebrating the liturgy in German, dressed as a layman. He began to preach in the same church where Luther ordinarily preached when he was in Wittenberg and demanded the abolition of images and the reform of the poor law.

Luther did not oppose all these changes, though he had a pastoral concern that the faith of the weak not be needlessly damaged by reckless liturgical changes. But he disliked Karlstadt’s replacement of old traditions and obligations with new puritanical prohibitions which destroyed the true freedom of the Christian.

Criticized by Luther, Karlstadt put away the academic dress he was entitled to wear as a doctor of theology and law. He donned the simple garment of a peasant, bought a farm, and loaded manure onto a cart along with other peasants. He announced that he would no longer promote students to theological degrees, since Christians are commanded to call no man master. (However, he did not give up his salary.) Thrown out of Saxony after further conflict with Luther (see p. 15), he allied himself for a short time with Melchior Hoffman. In 1529 he tried without success to wangle an invitation to the Marburg Colloquy. His last years were spent in Basel where he taught at the university, fought with the city’s clergy, and died of the plague.

JOHANNES OECOLAMPADIUS (1482–1531)

Johannes Hussgen’s hunger for learning led him to study at three different universities before finally receiving his doctorate at the advanced age of 36. His Hebrew was so good that he assisted Erasmus in the scholarly notes to his groundbreaking New Testament. Later their relationship cooled, but their mutual respect for each other’s scholarship remained. Like Melancthon (originally Schwartzerd) and others, Hussgen translated his surname (in formal German Hausschein or “house lamp”) into the Greek Oecolampadius, by which he is usually known today.

In 1521, already sympathetic to Luther’s teachings, Oecolampadius did an unexpected thing. He became a monk, either in response to inner spiritual conflict or to get more leisure for study. In a matter of months, his “Lutheran” sympathies got him in hot water. He suggested to the monastery that it ought to expel him as a heretic, walked outside, and jumped onto a waiting horse, riding back to Basel and away from the life he had so briefly embraced.

By this time he was 40, with no particular gifts in organization or leadership. A sensitive, rather indecisive scholar respected for his linguistic ability, he was hardly one of the movers and shakers of his generation. Upon his return to Basel, though, he displayed a new energy and confidence. His lectures on Isaiah began the move toward Protestantism in the city, and less than a year after his return he defended Protestant ideas in a public disputation, becoming the leading religious figure in Basel.

During the tumultuous 1520s, Oecolampadius worked closely with Zwingli and other reforming humanists such as Capito and Bucer. When Luther and Zwingli met at Marburg in 1528 to resolve their differences, Oecolampadius did much of the scholarly heavy lifting on the Zwinglian side. In one debate with Johannes Eck, Oecolampadius cited the church fathers, and Eck responded by appealing to the superior authority of Scripture—the reverse of the famous debate between Eck and Luther in Leipzig.

Like most of the reformers, Oecolampadius came to believe that his vows of celibacy were invalid and he should practice Christian discipleship in marriage. In 1528 he married Wibrandis Rosenblatt, a pious young widow of Basel—during Lent, at that (see “Bride of the Reformation,” p. 49). Only a month after Zwingli was killed in battle, Oecolampadius died of natural causes. His solid scholarship, gentle personality, and attention to nuance contributed to the rich fabric of reformed Protestantism; but in life and death, he never emerged from Zwingli’s shadow.

WILLIAM TYNDALE (1494–1536)

Tyndale, from a prosperous merchant family in west-central England, studied at Oxford and Cambridge. At the latter he joined an informal study circle at the White Horse Inn, discussing the new ideas of Erasmus and Luther with many future leaders of the English Reformation: Nicholas Ridley (1500–1555), Thomas Cranmer, and Hugh Latimer (c. 1487–1555).

In 1521 Tyndale returned to his birthplace as a tutor. To a visiting clergyman who claimed Christians could get along better without God’s laws than without the pope’s, he responded, “If God grant me life, ere many years pass I will see that the boy behind his plow knows more of the Scriptures than thou dost!”

Vernacular translations existed in Europe, but translating the Bible into English was illegal: authorities were concerned laypeople might misinterpret Scripture. The church banned controversial Oxford theologian John Wycliffe’s translation in 1408, and Lollards—followers of Wycliffe (1320–1384)—were still being burned at the stake as heretics in Tyndale’s day. Furthermore the Wycliffe Bible had been translated from Latin, not Greek and Hebrew, and its archaic language was difficult to understand. A new translation was both desperately needed and exceedingly dangerous.

In 1523 Tyndale went to London to persuade Bishop Cuthbert Tunstall to support his work. Tunstall was a friend of Erasmus, but he ignored Tyndale. After several frustrating years, Tyndale realized that nobody in authority would support him; his translation would have to be done on his own, outside of England. In 1524 he settled in Antwerp, a flourishing commercial center with a vibrant printing industry. Its fatal disadvantage: the Hapsburg family, committed to defending Catholicism and repressing heresy, ruled there.

Tyndale succeeded in publishing a translation of the entire New Testament in Worms in 1526. Bishop Tunstall and Cardinal Wolsey, lord chancellor of England, led the effort to find and burn copies of the subversive translation; English church authorities at one point bought up the entire stock in Antwerp to destroy them. Tyndale used the proceeds to produce a new and corrected edition. The church did not condemn his translation simply because it was in English, but because it clearly reflected the new interpretations of Scripture identified with Luther (see “An accidental revolution,” pp. 39–42).

Meanwhile Tyndale’s The Obedience of a Christian Man (1528) laid out a radical doctrine of royal supremacy and may have influenced Henry VIII’s developing understanding of his own independent authority. But his Practice of Prelates (1530) denounced the efforts being made to annul Henry’s marriage to Catherine of Aragon and counteracted the favorable impression The Obedience of a Christian Man had made on the king.

Thomas Cromwell worked to reconcile Henry and Tyndale and bring Tyndale back to England as a pro-government propagandist. But Tyndale stuck to his goal of giving access to the Bible in English for everyone in his homeland. If the king would promise this, Tyndale assured Cromwell, he would return to England, submit to the king, and never write another book of his own. No such promise came.

New chancellor Thomas More soon wrote three long treatises denouncing Tyndale as one of the most pernicious heretics of the day, and new bishop of London John Stokesley may have bribed a young Englishman to make friends with Tyndale and lure him to a place where he could be captured. Hapsburg troops arrested him in May 1535. He continued translating the Old Testament in prison until August 1536, when he was tried as a heretic and found guilty of Protestant beliefs. His translation, in itself, was not on the list of charges. Two months later he was strangled and his body was burned; his dying words supposedly, “Lord, open the king of England’s eyes.”

Breaking the English church away from Rome was for Tyndale only a necessary first step to the real passion of his life—putting the life-giving words of the Gospel into the mouths and hearts of every man, woman, and child in England. He embodied in his life and heroic death the Protestant commitment to the absolute authority of God’s Word, living out what Luther wrote: “The body they may kill, God’s truth abideth still, His Kingdom is for ever.”

PETER MARTYR VERMIGLI (1499–1562)

Protestantism penetrated more successfully in northern and western Europe, far away from Roman Catholic strongholds in the south. Yet some southern exiles did shape the northern Reformation, among them learned Italian refugee Peter Martyr Vermigli. As prior of an important monastery in Naples in 1537, Vermigli read the writings of Zwingli, Bucer, and Melancthon for the first time. Catholic reformer Juan de Valdès and his circle of “evangelical Catholics” also influenced him.

His new theological orientation and immersion in the writings of Paul were not universally hailed. Even though the pope lifted a ban on his preaching, it was only a matter of time before his sympathies would become apparent to the Inquisition. In 1542, after a prolonged crisis of conscience, he left Italy. In Strasbourg he served as a popular teacher of Hebrew and the Old Testament; but the Augsburg Interim (see p. 44), which also drove out Bucer, prompted Vermigli to accept the invitation of Cranmer to come to England.

There Oxford University appointed him Regius Professor of Divinity and made him a canon of Christ Church. Swept into controversies raging over the Lord’s Supper, he argued that though Christians do not sacrifice Jesus Christ anew in the Eucharist, they are called upon to sacrifice themselves in the response of faith.

When Queen Mary came to power, Vermigli returned to Zurich, where he provided a home for exiles from Mary’s England. When Elizabeth succeeded her, they returned, but he did not, though he was invited to do so and wrote them regularly. To travel from Zurich to London was an arduous journey for a young man, much less for an old professor of Hebrew. He died on a trip to France, an exile to the last. CH

This article is from Christian History magazine #118 The People’s Reformation. Read it in context here!

Christian History’s 2015–2017 four-part Reformation series is available as a four-pack. This set includes issue #115 Luther Leads the Way; issue #118 The People’s Reformation; issue #120 Calvin, Councils, and Confessions; and issue#122 The Catholic Reformation. Get your set today. These also make good gifts.

By David C. Steinmetz and Edwin Woodruff Tait

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #118 in 2016]

David C. Steinmetz (1936–2015) was Amos Reagan Kearns Distinguished Professor Emeritus of the history of Christianity at Duke Divinity School. All entries except Oecolampadius and Tyndale are adapted from his Reformers in the Wings (Oxford University Press, 2001), pp. 85–99, 106–113, 123–130, 138–152. Edwin Woodruff Tait is contributing editor at Christian History.Next articles

The people's Reformation: Recommended resources

Where can you go to learn more about the “people’s Reformation”? Here are some recommendations from CH editorial staff and this issue’s authors.

the editors