After Christendom, what next?

CH: This issue shows us how Charlemagne contributed to the idea of Christendom, the merging of throne and altar. Are we still in Christendom today?

D. Stephen Long: In a literal sense, I would say no. There are still pockets of Christendom. In Britain the queen and prime minister appoint the archbishop of Canterbury. And there are still leftovers of christendom in our modern culture. Every American president has to say “God bless America.”

There are also people who want to resurrect a new kind of Christendom. They are frustrated that leftovers are all that remain. Some may not even realize that Christendom is gone and won’t return.

CH: How then should church and culture relate today?

DSL: Theologian Karl Barth said that the end of Christendom has set the church “free for the service to its own cause within the secular world which it had for the most part neglected in pursuit of its own fantasies.”

Christendom recognized the power of the church, though it didn’t recognize it properly. It was a secular recognition of church power, trying to contain that power within another power. But—and I think this is more so with Charlemagne than even Constantine—it was antithetical to the power revealed in the Gospels.

The loss of Christendom is a new opportunity. Look at the papacy. When we had Christendom, we had secular popes. Markus Wriedt said that now that the culture has become more secular, the pope has become more Christian. The church no longer needs to be accountable to the kind of politics present in Christendom. That frees it up to be a truly political force of its own.

The church is a transnational body. Our most important identity is in baptism, and our primary obligations are to other Christians. But we are still obligated to our neighborhoods, our villages, our cities. The Epistle to Diognetus, an early Christian letter, tells us to live in the midst of our neighbors and love them all: “[Christians] dwell in their own countries, but simply as sojourners. As citizens, they share in all things with others, and yet endure all things as if foreigners. Every foreign land is to them as their native country, and every land of their birth as a land of strangers. . . . They pass their days on earth, but they are citizens of heaven. They obey the prescribed laws, and at the same time surpass the laws by their lives.”

We need once again common life, common worship, common discipline, common teaching. Not uniformity, but something recognizable from place to place.

CH: Two themes prominent in Charlemagne’s story are Christian-Muslim relations and the involvement of the church in education. Where are we on those themes today?

DSL: Christians understand ourselves as transnational. We should not then try to make Islam fit within national politics. In that sense I am more than willing to concede Islam space as part of common decency. But there needs to be a better way of dialogue going forward. Islam, Christianity, and Judaism are all essentially social, with political significance.

As far as education, I’m not sure Christians need their own educational institutions as much as new ways to educate people in the basic teachings of the faith. I tell people to ask their pastor if he or she knows their Myers-Briggs letters and then ask their pastor to explain the hypostatic union. I would argue that far more pastors know the first than the second. But knowing how the divine and human natures of Christ relate is more important for the future of the faith. Clearly we need some new ways of teaching. I’d love to see ecumenical schools emerge, places like the Scriptural Reasoning Project, talking from the orthodox heart of the faith, not its margins. We need to advocate for space for faith in the academic world; otherwise we will not have wiser, saner voices speaking of faith. When you police out confessional voices, that backfires.

CH: How can the Christian tradition help us here?

DSL: Besides the Epistle to Diognetus, I think we can learn from Augustine’s two cities in The City of God. Both maintained that our earthly politics are made relative in the face of God’s kingdom. That would be my criticism of Charlemagne—that his earthly politics were too central.

Gerald Schlabach has said, following Stanley Hauerwas, that Catholics and Anabaptists both need to become more like each other. Christians can’t continue with the “counters”—where the one thing Catholics know is that they’re not Protestant and the one thing Protestants know is that they’re not Catholic. Think back to Origen, Tertullian, and Augustine on politics. They were not necessarily against the empire, but they knew what they were for. They were for the fact that Jesus Christ is Lord. CH

By D. Stephen Long

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #108 in 2014]

D. Stephen Long is professor of systematic theology at Marquette University.Next articles

Recommended resources

Recommendations by CH editorial staff and this issue’s contributors

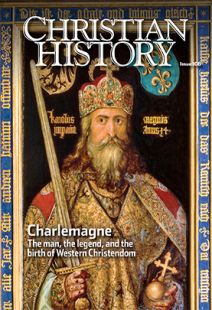

the EditorsThe thousand lives of Charlemagne

How medieval poets turned a border skirmish into a foundational medieval legend

David A. Michelson“Father forgive them”

The persecution of Christians in modern history: staggering numbers, inspiring stories

Christof Sauer and Thomas SchirrmacherStart seeing persecution

How Westerners overlook persecution, what it looks like, and what we can do about it

The editors and Roy Stults