After the revolution

MARTIN LUTHER spent the early years of the Reformation battling the Roman Catholic establishment. But it wasn’t long before the fledgling movement was battling itself. In the mid-1520s Luther was forced to respond to the first major splits within the Protestant ranks. He faced a popular uprising known as the Peasants’ War. At the peak of the uprising, expecting imminent death, Luther decided to further break with tradition: he married. Then he became increasingly involved in building what became Lutheranism. And in his final years, convinced he was living in the last days of the world, he issued violent treatises against all the enemies of God as he saw them—Catholics, “fanatical” Protestants, Turks, and Jews.

It is one thing to picture a new vision of the Christian faith, but it is quite another to give this vision form to pass down through generations. Luther’s turbulent later years began with a major turning point in 1525.

Creating a church

In that year Luther married 26-year-old former nun Katharine von Bora (see “Momentous vows,” pp. 28–32, and “Mother of the Reformation,” p. 33). From their inauspicious beginning, Martin and Katie developed love and respect for each other; Luther called his favorite Pauline epistle, Galatians, “my Katharine von Bora.”

In 1529, to define Lutheran beliefs, Luther issued the Small Catechism and the Large Catechism. These taught the fundamentals of Lutheran Christianity to a population distressingly ignorant of even the basics of the faith. A great lover of music, Luther also wrote numerous hymns, many of which are still sung today—the most famous being “A Mighty Fortress.”

In 1530 Luther’s colleague Philipp Melancthon (see “Preachers, popes, and princes,” pp. 39–44) penned an enduring summary of the Lutheran faith in the Augsburg Confession. The Confession was meant to approach the Roman Catholic position as closely as possible without surrendering any crucial issues. It summed up the Lutheran position and listed Catholic abuses that Lutherans felt needed to be corrected (for example, prohibiting clergy to marry and withholding the Eucharistic cup from the laity). The Confession remains a defining doctrinal statement for the Lutheran branch of Christianity. As institutional Lutheranism developed, Lutheran political leaders gained increasing influence. In 1531 the Schmalkaldic League, an alliance of Protestant princes, was formed to defend German states that subscribed to Lutheranism against possible Roman Catholic attack. In 1536 Lutherans and Protestants in southern Germany reached a concord on the Lord’s Supper. The southern German Protestants accepted the Lutheran insistence that Christ’s body and blood were received in the Lord’s Supper even by the “unworthy,” and Lutherans let drop the question whether this also applied to the “godless.” Not incidentally the agreement also regularized a military alliance between these northern and southern parties.

In 1539 Luther produced a famous treatise on the doctrine of the church, arguing that it could not depend upon church fathers and the councils to establish its faith, but only on Holy Scripture. Councils had no authority to introduce matters of faith or new works, but only to defend faith and good works found in Scripture.

Meanwhile in 1535 Pope Paul III had announced a general council to settle the growing schism. It took 10 years before it actually convened at Trent [more on this in an upcoming issue—Editors]. Protestant princes rejected the Council of Trent for religious and political reasons, although some Protestant theologians, including Luther, argued that Lutheran princes should attend.

While Luther took part in all these political and religious maneuverings, he still continued his theological and pastoral labors. In 1534 he and his colleagues completed their German translation of the Bible, which has greatly influenced German language and literature ever since. Luther also lectured on biblical books from both the Old and New Testaments, helping the University of Wittenberg prepare the hundreds of new pastors now needed to bring the Reformation to the grassroots.

Ordering obedience

By his own admission, Luther was an angry man. Anger was his defining sin. But when directed against the enemies of God, it helped him, he said, to write well, to pray, and to preach: “Anger refreshes all my blood, sharpens my mind, and drives away temptations.” Though he knew his harshness and anger offended some, Luther retorted: “I was born to war with fanatics and devils. Thus my books are very stormy and bellicose. I must root out the stumps and trunks, hew away the thorns and briar, fill in the puddles. I am the rough woodsman, who must pioneer and hew a path.”

Luther’s anger grew as he aged, as evidenced in his vitriolic attacks on the Peasants’ War of 1525. In 1524 some German peasants rebelled. Reformation ideas were one possible cause, although economic oppression was involved as well. Little by little, the uprising spread among the peasants’ weary and oppressed comrades.

The peasants listed Luther as an acceptable arbiter of their demands, and he attempted to mediate. Luther first blamed the unrest on rulers who persecuted the Gospel and mistreated their subjects. Many of the peasants’ demands were just, he said, and for the sake of peace, the rulers should accommodate them.

On the other hand, Luther warned the peasants that they were blaspheming Christ by quoting the Gospel to justify their secular demands. In fact, he argued, the Gospel teaches obedience to secular authorities and the humble suffering of injustice (see “The political Luther,” pp. 34–36).

As unrest spread Luther began to side with the princes. In May 1525 he wrote Against the Robbing and Murdering Horde of Peasants, in which he urged the princes to “smite, strangle, and stab [the peasants], secretly or openly, for nothing can be more poisonous, hurtful, or devilish than a rebel. It is just as when one must kill a mad dog; if you do not strike him, he will strike you and a whole land with you.”

Luther had his way. The peasants were brutally suppressed, and Luther’s advocacy of their violent repression remains controversial to this day.

Fighting for the faith

Next Luther turned his wrath and attention to a controversy over the meaning of the Lord’s Supper. Other reformers—Ulrich Zwingli of Zurich, John Oecolampadius of Basel, and Martin Bucer of Strasbourg—denied Christ’s physical presence in the bread and wine. They acknowledged Christ is truly present, but this spiritual presence was not tied to the bread and wine; it depended upon the faith of the communicants.

Luther believed Christ’s words “This is my body. … This is my blood. … ” mean that Christians receive the body and blood of Christ “in, with, and under” the bread and wine. For Luther, to call this into question was to deny the promise of Christ and undercut the Incarnation. He believed the essence of the Gospel was at stake (see “Christ present everywhere,” pp. 23–25).

Luther and other reformers gathered in Marburg in 1529 to hammer out an agreement—but none was reached. Luther angrily denounced his opponents, saying he could no more accept their position than deny the doctrine of justification by faith alone.

But even this was not Luther’s last vehement denunciation. In the years just before his death, he issued several ferocious (and for admirers both then and now, embarrassing) treatises. Why were they so fierce?

Attacking the Devil

Luther’s reading of the Bible convinced him that practically from the beginning of the world, there had been a perpetual struggle between the true and false church. What happened to the prophets and apostles could and would happen to the church of his day. Naturally Luther concluded the papacy was the Antichrist. Protestant opponents were “false brethren,” like those who had plagued the true prophets and apostles. The Turks, who threatened Europe from the east, were for him a clear sign of the end times: they represented Gog and the little horn in the Book of Daniel. Jews were suffering God’s wrath for rejecting the true Messiah.

Behind all these members of the false church, Luther thought, looms the Devil, the father of lies. Often Luther directed his attacks not at his human opponents but at the Devil, whom he saw as their master. Of course, for Luther no language was too harsh when attacking the Devil.

It would be tempting to dismiss these writings as aberrations, as “medieval remnants,” or as the simple products of old age or ill health, but these “last testaments” accurately express Luther’s views and are integral to his theology. Luther’s poor health and old age may have exacerbated his anger, but these attacks are consistent, in content and passion, with his earlier writings.

In Luther’s later years, his health, delicate even as a monk, gradually declined. He suffered from constipation, diarrhea, hemorrhoids, dizziness, ringing in his ears, an ulcer on his leg, kidney stones, and heart problems. He also experienced bouts of depression (battles with the Devil, he called them); and the question, “Are you alone wise?” gnawed at him.

But his many maladies hardly slowed his productivity. Excluding Bible translations, Luther produced some 360 published works from 1516 to 1530. From 1531 to his death, he added another 184 to this incredible total. At the same time, he lectured regularly at the university, preached for long stretches in the parish church, wrote hundreds of letters, advised German princes, and closely followed the events of his day.

In a letter of January 1546, Luther described himself as “old, decrepit, sluggish, inactive, and now one-eyed,” hoping for a “well-deserved rest” but still overloaded with writing, speaking, acting, and doing. A week later he was off on business once again, making his third trip to Mansfeld to mediate a dispute between Mansfeld’s two rulers. On February 18, on this trip, he died in Eisleben. In his pocket were the beginning pages of a projected manuscript against Roman Catholics. To his last breath, the “rough woodsman” was resisting “Satan’s monsters.”

In another pocket, though, another slip of paper was found. Perhaps Luther carried it to remind himself of his limitations.:

No one can understand Virgil in his Bucolics unless he has been a herdsman for five years. No one can understand Virgil in his Georgics unless he has been a farmer for five years. No one can fully understand Cicero in his letters unless he has spent twenty-five in a great commonwealth.

Let no one think that he has sufficiently tasted Holy Scripture, unless he has governed the churches with the prophets, such as Elijah and Elisha, John the Baptist, Christ, and the apostles, for a hundred years.

Touch not this divine Aeneid. Rather, fall on your knees and worship at its footsteps. We are beggars, that’s the truth. CH

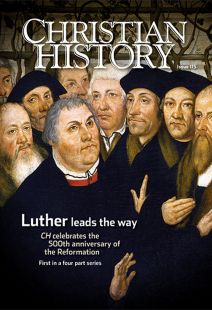

Christian History’s 2015–2017 four-part Reformation series is available as a four-pack. This set includes issue #115 Luther Leads the Way; issue #118 The People’s Reformation; issue #120 Calvin, Councils, and Confessions; and issue#122 The Catholic Reformation. Get your set today. These also make good gifts.

By Mark U. Edwards Jr.

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #115 in 2015]

Mark U. Edwards Jr. is an advisory member of the faculty of divinity at Harvard Divinity School and the author of Luther’s Last Battles: Politics and Polemics, 1531–46 and Printing, Propaganda, and Martin Luther. This article is adapted from CH 39.Next articles

What did Luther know and when did he know it?

When did Luther discover justification by faith?

Edwin Woodruff TaitLuther Led the Way, Did You Know?

Luther loved to play the lute, once went on strike from his congregation, and hated to collect the rent

the editors and othersThe man who yielded to no one

Erasmus “laid the egg that Luther hatched,” many said; why aren’t we celebrating his 500th anniversary?

David C. FinkPreachers, popes, and princes

The men who mentored Luther, fought with him, and carried his reformation forward

David C. Steinmetz and Paul Thigpen