Building emerging India

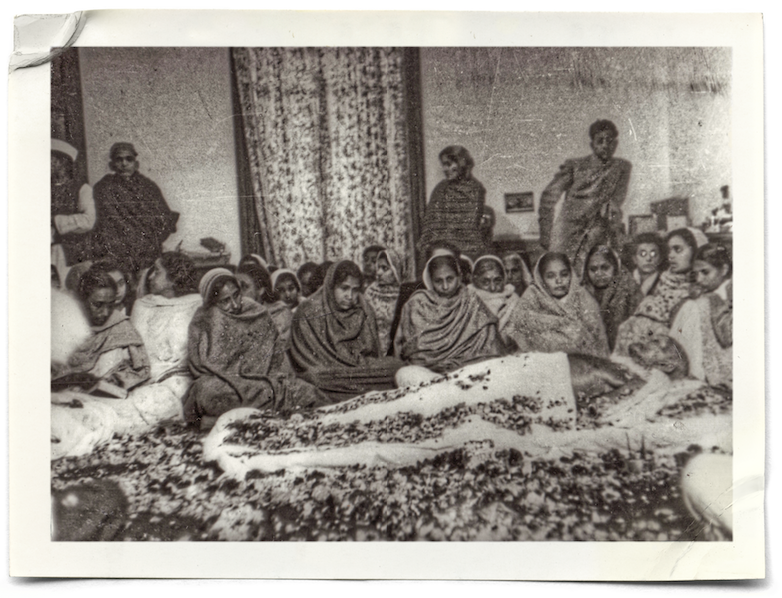

[Gandhi’s Body surrounded by mourners, 1948. Unknown photographer / Accessed 7/28/2020: whokilledgandhi.com/galleries/photos/]

E. Stanley Jones met Mahatma Gandhi for the first time in 1919 at St. Stephen’s College, Delhi. They did not meet again until 1924 in Poona when Gandhi was temporarily released from jail to attend to a medical need. But they remained in touch with each other continually; helping, inspiring, and prodding one another on in their mutual quest. On one of Jones’s visits just before he returned to the United States, he asked Gandhi for a message to take back with him to the West as to how we should live this Christian life. Gandhi replied: “Such a message cannot be given by word of mouth; it can only be lived.”

Jones often visited Gandhi’s Sabarmati Ashram and stayed with him, sometimes for several days, to continue his unlearning and new learning about Indians’ pain, struggles, and challenges before presenting Christ to them. Gandhi sent 13 known letters to Stanley Jones, signing five; Mabel Lossing Jones also corresponded with Gandhi for over 25 years on educational subjects for underprivileged communities, particularly the education of girls. Eunice and James Mathews later remained friends with Gandhi’s family for over 50 years.

A call and a collapse

Friendship with Gandhi helped Jones answer many of his questions about presenting the gospel in India. Despite the lack of a ceremonial farewell by the Methodist mission board, Jones had been joyful and eager as he began his missionary journey on October 13, 1907. After landing on November 13 at Bombay (now Mumbai), he boarded a train to reach his first posting at Lucknow. During the train ride, an educated and intellectual Muslim family traveled in his compartment.

Jones began sharing about Christ, hoping the Muslim family would be seeking baptism by the end of the journey; instead they shared about Islam and the goodness of their religion. After they had traveled together for several hours, Jones secured no result, no baptism. This event left him perplexed.

This trend continued even after he became pastor at Lal Bagh Methodist Church, Lucknow. Jones found that many perceived Christianity as yet another addition to India’s multireligious, multicultural, and multilingual faiths. The educated intellectuals and the leaders of India did not find Christianity, a religion of the British Empire, to be in any way inspiring, challenging, or life-changing. Everything Jones knew about how to be a missionary in a foreign land failed in the Indian context.

Self-doubt began to creep in. He wondered: what is wrong—method, message, messenger, or place? He wrote, “So at the end of my first term as missionary I ended up with a Call and a Collapse.” Mentally, spiritually, and physically exhausted, he left on furlough in 1916. Still believing that he was done for, he returned the next year.

In this context the first meeting between Jones and Gandhi took place in 1919. Sushil Rudra, the principal of St. Stephen’s College, Delhi, introduced Jones to Gandhi. During the conversation Jones asked, “What must Christians do to make Christianity naturalized in India?” Gandhi replied,

All Christians must live more like Jesus Christ. You should practice your religion without adulterating it or toning it down. You should emphasize the love side of Christianity more, for love is central to Christianity, and you must study more sympathetically the non-Christian religions to find the good in them and to have a more sympathetic approach.

That meeting soon put Jones on a path beyond mission compounds and church boundaries into the struggle of the people of India to become an independent nation. He wrote, “I found myself very early taking sides with [Gandhi] in the political struggle.” Jones joined in the rising Indian nationalism of the 1920s, which led directly to The Christ of the Indian Road.

A missionary statesman for India

Jones began seriously to work on learning his context, reading the religious literature of Hinduism and Islam as well as current psychological, religious, and philosophical literature relevant to his ministry. As he did so, he kept an eye on news and events.

On one side was the so-called Christian British Empire ruling India, and on the other side, non-Christian India striving to be free from the British Empire. Which side would Jones and the Christ that he was preaching take? The people of India were asking, “Would your Christ support enslavement of the people even if it is done by a Christian group?” Jones knew the obvious answer is “no.”

But Jones also knew that, on the other side, Indian groups seeking independence were ruthlessly and violently divided on religious lines. Sporadic eruptions of riots between Hindus and Muslims occurred. If the British left India, what kind of India would emerge? Would it be an oppressive Hindu India or would Muslims find security in their new independence? Jones believed that his missionary task demanded that as a statesman he bring the two warring sides, Hindus and Muslims, together into harmony and unity; into a common struggle against a common power to achieve a common goal of a new, independent nation.

At the same time, something called the “Mass Movement” was taking place under the leadership of another Methodist missionary, J. Waskom Pickett, also an Asbury University alumnus. This movement formed among the depressed classes of India who were seeking social transformation from the curse of untouchability laid on them by the upper castes, while longing for upward mobility in terms of education. It was proving to be a success; huge numbers of people were being baptized and coming into the Christian fold.

Jones worked diligently to prepare himself for his new task of presenting Christ to the educated people of India who were divided on religious lines and fighting against the “Christian” British Empire. He was surprised to find that, among the educated classes, many already practiced Christian principles in their lives and work, but they did not seek baptism or join a church. Jones recognized that the Holy Spirit was at work far beyond the borders of the Christian church; Christ was coming to meet people in India through other means.

He began to think that Gandhi would be a representative of this irregular channel of Christianity. At one point in 1926, he wrote to his friend and put the cause of Christ before him, saying:

“I think the ideas that underlie the sermon on the mount have gripped you and have, in a great measure, moulded you, but to me the centre of Christianity is this radiant Person of Christ. He himself is the Good News.”

His friend responded:

“I appreciate the love underlying the letter and kind thought for my welfare. But my difficulty is of long standing. The matter has been presented to me before now by other friends. I cannot grasp the position through the intellect. It is purely a matter of the heart.”

As a result Jones wrote his supervisor, Ralph Diffendorfer, and asked him to have the staff of the missions board “covenant in prayer for the revelation of Jesus Christ to come to the Mahatma.”

Meanwhile Jones began to openly and repeatedly favor Indian self-rule (Swaraj) as a birthright of all Indians. As a result of this open and outspoken stand, British authorities regarded Jones with increasing unfriendliness. This antipathy by the British imperial powers grew to such a level that it resulted in his being denied a visa to return to India during World War II.

Building a new India

Of Jones’s three well-known initiatives that made significant contributions to the building of a new India, Gandhi’s influence can be seen in two. First, of course, were the Round Tables. The name came originally from a series of meetings and negotiations between Indian groups led by Gandhi and the British government. Jones applied this metaphor from the political arena to bring the different religious groups together to meet and to share with each other (see p. 16).

It would be naïve to reduce the Round Table Conferences to religious “feel-good” gatherings to score a point here and a point there, or even to convert others, although this certainly happened. Jones was working on a bigger picture: bringing all the religiously diverse groups together in the common struggle to build a new nation.

Meanwhile this ongoing freedom struggle was being nurtured, discussed, and envisioned in secluded places like ashrams, away from the prying eyes of the British Empire. Several ashrams emerged during that time, founded by various Indian leaders involved in the freedom struggle. The ashram became a place of living out the ideals and the vision of a new India in miniature.

Gandhi, who had experienced the Tolstoy and Phoenix Ashrams in South Africa, started the Sabarmati Ashram in Gujarat in 1917 and, much later, the Sevagram Ashram in Maharashtra in 1936. Famous poet Ravindranath Tagore started the Shanti Niketan Ashram in Bengal in 1901.

Jones too started an ashram that supported, helped, and propagated the making of a new India at Sat Tal, Nainital, in 1930 (see pp. 12–15). Jones described it as a forest school for meditation and prayer where non-Christians would be invited to participate. Here all lived in modest Indian style, wearing Indian clothes, eating simple Indian food, and doing menial and manual work with few or no servants.

The purpose was to build a community of the Kingdom of God more in touch with the soul of India. A stone tablet there declares even today, “All are welcome, the people of all faith and of no faith, to have a live-in experience of the Kingdom of God in a miniature.” The lifestyle of Sat Tal Ashram provided a model for the emerging nation: an equality rising above the differences of religion, caste, class, regional, ethnic, and linguistic lines to form a loving, sharing, and caring community as exhibited by the early Christians in the book of Acts.

Do you mean it?

Jones’s third contribution to an independent India—the division of India and Pakistan—brought him into conflict with his old friend. Jones saw his participation in these negotiations as a way to use his neutrality as an American citizen, and the neutrality of the Christian religion, to provide a common and fair meeting ground for the proponents of different religious and political groups. Gandhi took a different view.

In the early 1940s, Jones heard for the first time of “Pakistan” (meaning “a holy place”), a Muslim nation that would be carved out of India by the Muslim League after gaining independence. The league was an exclusive Muslim political party also involved in the freedom struggle. Jones asked the leader of the Muslim League, Mohammad Ali Jinnah, “But you do not mean it, do you?” Jinnah replied, “Yes, we do.”

Jones initiated negotiations to resolve the deadlock between the two sides. On one side was the Indian National Congress—a political front of both Hindus and Muslims combined to fight for freedom; on the other side was the Muslim League. He attempted to reconcile the Hindu and Muslim leaders—including Jawaharlal Nehru, the proponent of one combined secular India, and Jinnah, the main proponent of Pakistan.

Gandhi earnestly tried to hold India undivided, strongly believing it a sin to separate one body into two nations. But he also believed the solution lay in not denying the division, which was becoming clearer day by day as riots between Hindus and Muslims erupted amid the freedom struggle.

In 1946 Jones wrote a letter to Jinnah suggesting that the Indian National Congress should concede Pakistan and make an India Constituent Assembly and Pakistan Constituent Assembly. Both could work out their respective constitutions and then come together to make a federal union, one united nation of India. Jinnah agreed to this idea during his talk with Jones, but then formally rejected the proposal in writing. When Jones brought it to Gandhi, Gandhi responded: “Even the very idea of such a conception of a Pakistan is a sin, and you a man of God, I am surprised, would approve such a thing which is sin.”

Triumphal march

Despite their differences on this issue, Jones and Gandhi continued their common struggle toward a “Holistic Self-Rule” (Purna Swaraj) of the Indian people; driven not just by political and economic freedom for self-governance, but by a sociocultural and spiritual need arising out of the 300-year-long British enslavement of mind, body, and land. When the British left in 1947 and the country was indeed partitioned, the resulting violence led indirectly to Gandhi’s assassination on January 30, 1948, by a Hindu nationalist and raged on for years.

Jones’s biography of Gandhi, written soon after his friend’s death, showed his extraordinary admiration as he wrote: “[Gandhi] marched into the soul of humanity in the most triumphal march that any man ever made since the death and resurrection of the Son of God.” Jones admitted that Gandhi had taught him more about the spirit of Christ than perhaps any other man in East or West. On the martyrdom of Gandhi, he commented, “Never did a death more fittingly crown a life, save only one—that of the Son of God.” CH

By Naveen Rao

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #136 in 2020]

Naveen Rao is principal of Leonard Theological College in Jabalpur, India, and author of several books. He is ordained in the Methodist Church in India and has ministered with the Sat Tal Ashram for a number of years.Next articles

Salt and a narrow escape

The unruly crowd surrounded Mabel's car, rocking it

Martha Gunsalus ChamberlainWhen the church goes to market, Did you know?

The church and economics from the parables to Brother Cadfael to missionary presses

The editors and contributorsEditor's Note: When the church went to market

What should be the relationship of Christians to economics and the market?

Jennifer Woodruff Tait