Caspar Schwenckfeld von Ossig: A Gallery of Associates

Valentine Crautwald

BORN AT NEISSE, Silesia, Crautwald attended the University of Cracow and became secretary to the Bishop of Breslau in 1514. A highly learned scholar, strongly affected by the humanist movement of the day, he met Schwenckfeld in 1523 and two years later, after Schwenckfeld spoke to him about the controversy over the meaning of the Lord’s Supper, Crautwald had a vision during which he came to what would be the distinctive Schwenckfeldian understanding of the Supper.

Together with Schwenckfeld he worked assiduously for the reformation in Liegnitz and after the latter’s self-exile in 1529, in spite of his increasing isolation in his own country, he wrote and studied in defense of the Schwenckfeldian cause until his death in 1545.

Adam Reissner

THE EXACT DATES of Reissner’s life are unknown. He was born sometime between 1496 and 1500 in Mindelheim in south Germany and died after 1576, but before 1582. He attended the University of Ingolstadt as a young man and there studied Hebrew and Greek under the famous Johann Reuchlin. For some years he was at Wittenberg.

In 1531 he met Schwenckfeld in Strasbourg and became a loyal follower. In spite of this he was able to maintain his position as municipal clerk in his Catholic home-town until 1548. From then until his death he dedicated himself to the Schwenckfeldian movement, serving as secretary to Schwenckfeld and aiding in the publication of his works as well as writing books of his own.

Michael Hiller

A SILESIAN PASTOR and pro-Schwenckfeldian, Hiller produced sermons with a strong mystical bent. These sermons were among the most copied works next to those of Schwenckfeld himself among later Schwenckfelders. Hiller died in the late 1550s.

Johann Werner

AN EARLY DEFENDER of Schwenckfeld, Werner was a preacher at the Church of St. Peter and Paul in Liegnitz. His Catechism and Sermons were favourites of Schwenckfelders to the mid-nineteenth century.

Erasmus Weichenhan

FROM 1538 TO his death in 1598 this strongly pro-Schwenckfeldian Silesian pastor compiled what would be the favourite collection of sermons used by the Schwenckfelders down to this century.

Antonius Oelsner

A SILESIAN SHEPHERD, Oelsner had read Schwenckfeld in his youth and was converted in 1580. Thereafter he had visions and began to wander about the Silesian countryside preaching. He was imprisoned for two years and on his release took up his preaching again. He was sentenced as a galley—slave in 1595.

Daniel Sudermann

A RESIDENT OF Strasbourg in the early 1600s, a significant poet and student of mysticism, Sudermann played an important role in collecting and saving Schwenckfeld manuscripts. For a time he owned Schwenckfeld’s annotated Bible (now preserved in the Schwenckfelder Library [see The Schwenckfeld Bible]).

Martin John, Jr.

PERHAPS THE MOST significant personality among Schwenckfelders in the later 1600s, Martin John Jr. was remarkably well read in the radical theological literature of his day, and was responsible for a renewal among the Schwenckfelder communities which remained in the Harpersdorf area.

In the spring of 1669 he and his wife Ursula made a journey through Germany and into Holland visiting kindred spirits. When the Pietist Awakening began a few years later he came into close contact with many of its adherents and introduced his Schwenckfelder fellow-believers to it.

Sybilla Eisler

THE WIFE OF a councilman in the city of Augsburg, Eisler has the distinction of having received more letters from Schwenckfeld than any other person. Particularly attracted to Schwenckfeld’s theology, she not only prodded him to express himself on a number of questions, but played a major role in preserving his correspondence.

Agatha Streicher

A NOTED PHYSICIAN, Streicher was a member of a family especially devoted to Schwenckfeld. She was present at his death in her family’s home in 1561 and wrote an account of the last months of his life.

George Weiss

THE FIRST PASTOR among the Schwenckfelders in America, Weiss played a prominent role in defending the Schwenckfelder cause during the Jesuit persecution and directing the emigration to Saxony and America [see the article Freedom in Pennsylvania]. An informed theologian he was well-versed in Latin, Greek and Hebrew, worked energetically on the compilation of a Schwenckfelder hymnbook, and worked to bring cohesion into the group in its first six years in America. He died in 1740.

Balthasar Hoffmann

PERHAPS THE MOST astute of the 18th-century Schwenckfelders, Hoffmann was transcribing Schwenckfelder documents when he was eleven years old. In 1721 he travelled with his father Christopher and another representative, Balthasar Hoffrichter, to the Imperial Court in Vienna to plead for toleration in the midst of the Jesuit persecution in Harpersdorf. He remained there for five years before returning home to join the emigration first to Saxony and then to America.

Taking over the leadership role in America after Weiss’s death in 1740, Hoffmann continued his pastoral role among the Schwenckfelders both in a formal and informal way until his death in 1775. A prolific copier of manuscripts, poet, and theologian, he produced three large treatises in biblical studies, and a great many other works.

Christopher Schultz

ONLY 16 YEARS OLD at the time of the 1734 emigration, Schultz came to America as an orphan, and kept the most extensive diary account of the journey to Pennsylvania.

An avid student of Schwenckfelder theology he took a major leadership role in the group in 1764, compiled the first hymnbook of the American Schwenckfelders (published in 1762), wrote the first significant Schwenckfelder history entitled Vindication of Caspar Schwenckfeld and a large compendium of the Christian faith. With his cousin Christopher Kriebel he helped shape the Schwenckfelder school system. He died in 1789.

By the Editors

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #21 in 1989]

Next articles

Christian History Chronology: The Hard Journey to America

One Schwenckfelder left us an account, in diary form, of the crossing to Pennsylvania.

the EditorsFrom the Archives: Christian Self-Surrender

If we seek God only for the sake of His pure goodness, and not desire more than His pleasure, reward will follow without our seeking.

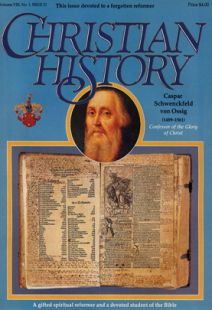

Caspar Schwenckfeld