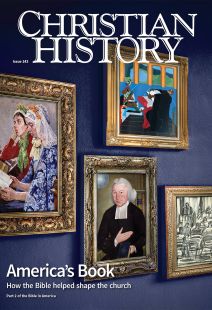

Old book in a new world

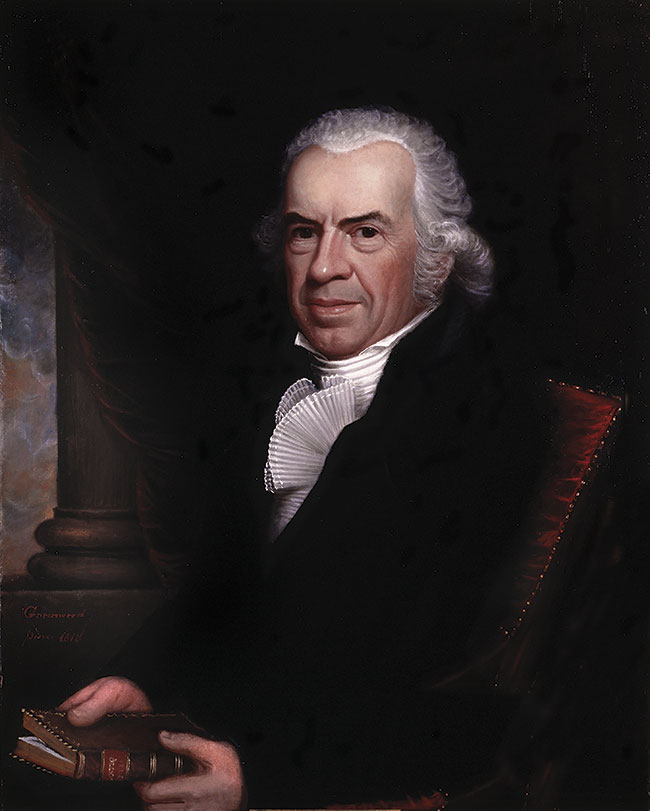

[Ethan Allen Greenwood, Portrait of Isaiah Thomas, 1818. Oil on panel—The American Antiquarian Society]

In 1630 Massachusetts founding governor John Winthrop (1588–1649)—of “city on a hill” sermon fame (see CH #138)—brought his own personal copy of the King James Version ashore: the first known KJV on American soil. But this was something of an aberration; a solid majority of the earliest colonists preferred their Puritan-friendly Geneva Bible. In fact, given the popularity of that version at the time, Winthrop’s KJV seemed destined to remain a mere curiosity.

Within two decades, however, the KJV was well on its way to becoming The Bible of the New World. As the Geneva ceased publication in 1644, British-printed KJVs flowed into American churches, homes, and libraries. And when, in the late 1700s, KJVs began issuing from American presses, the floodgates opened.

By the 1800s American editions numbered in the millions, and the KJV was singing its cadences through the greatest American novels, shaping the solemn phrases of presidential speeches, and changing the American language itself with hundreds of new idiomatic phrases.

Beloved above all in the churches, the KJV became so dominant by the 1900s that in 1936, a scholar complained that many Americans “seemed to think that the King James Version is the original Bible which God handed down out of heaven, all done up in English by the Lord himself.”

1777 saw the first publication of the KJV on American soil, a New Testament printed by Robert Aitken (1734–1802) of Philadelphia during the Revolution. Four years later he released his full Bible after petitioning Congress for support in his enterprise (they granted it). Aitken printed 10,000 copies. But the Aitken Bible struggled against better-printed, cheaper editions shipped from England—in fact, he took a significant financial hit on the project, losing over £3,000.

Revivals and Bibles

American Bible publishing broke wide open with the dawning of the 1790s, when came the first stirring of renewed revivalism since the Great Awakening of the 1740s. These would quickly build into a veritable evangelistic tidal wave (see pp. 11–13).

First came emotional frontier camp meetings in places like Cane Ridge, Kentucky; then the aggressive revivalism of Charles Finney (1792–1875) in the “burned-over district” of upstate New York; a sudden eruption in the late 1850s of noontime prayer-and-testimony meetings in major East Coast cities; and the genteel but power-packed midcentury parlor meetings and camp meetings of Phoebe Palmer (1807–1874) and her Wesleyan Holiness colleagues. Eventually the movement culminated in the late-century mass evangelism and Bible conferences of D. L. Moody (1837–1899). Countless conversions and a boom in church growth created a nationwide thirst for more Bibles.

By 1800 Americans could acquire 70 different printings from the presses in 11 different towns; by 1840 more than a thousand printings. One who capitalized early on the Bible-publishing boom was craftsman-scholar Isaiah Thomas (1749–1831). This self-educated printer, one of Paul Revere’s group of riders, made himself the leading publisher and bookseller after the Revolution. He printed magazines, an almanac, the first dictionary in America, and what he hoped would be the first “completely correct” KJV—with and without the Apocrypha according to taste. (It is a myth that Protestant Bibles did not include the apocryphal books, at least in the first half of the nineteenth century.)

Thomas’s most remarkable innovation, though, was his unique payment arrangement. Seven dollars, the price of his Bible, was a lot of money in those days. So Thomas agreed to take up to half of that payment in “Wheat, Rye, Indian Corn, Butter, or Pork.”

Despite Thomas’s valiant attempts at precision, it was the 1791 Bible of Delaware Quaker Isaac Collins (1746–1817) that became the standard for accuracy. It included a longer concordance, frequent marginal notes and, between the two testaments, a detailed account of the basic argument of each book in the Bible. It also deleted the standard dedication to King James and put in its place an address to the reader by John Witherspoon (1723–1794), president of the College of New Jersey (Princeton University) who served for six years as a congressman. Nearly a dozen other Bibles or New Testaments were produced in America during the years 1791 and 1792.

A Bible for every American

By the early 1800s, multiple versions of the KJV inundated the market. Mason Weems (1759–1825), famous for making up the story about George Washington and the cherry tree, sometimes earned his living as a traveling Bible salesman. Shortly after 1800 Weems wrote from Virginia to his publisher in Philadelphia about the various KJV editions he was retailing:

I tell you this is the very season and age of the Bible. Bible Dictionaries, Bible tales, Bible stories—Bibles plain or paraphrased, Carey’s Bibles, Collins’ Bibles, Clarke’s Bibles, Kimptor’s Bibles, no matter what or whose, all, all, will go down—so wide is the crater of public appetite at

this time.

Crucial to this mushrooming growth of Bible sales were new Bible societies founded in America in the 1800s, along with associated Sunday school and tract societies. Many such societies were local groups of citizens who bought Bibles at cost for resale to their neighbors. Their goal: to put a Bible in the hands of every American.

When in 1816, 34 of these societies joined to form the American Bible Society, they launched into achieving this goal with a will. The ABS printed the King James Version in almost 60 different forms by 1850. Its output in 1829 alone was an astounding 360,000 Bibles—at a time when first editions of books usually topped out at around 2,000! In 1845 that number increased to over 417,000; in each year of the 1860s, the ABS printed over a million Bibles.

Such powerhouses were Bible publishers in America during the 1800s that they drove technical innovations in their industry: paper quality improved, stereotypes replaced costly standing type, power presses multiplied output, and in-house binding reduced costs.

Of course someone had to sell all these Bibles, and the 1840s saw the innovation of the “colporteur”—the door-to-door Bible salesman. The ABS soon employed a national network of these hardy folks, and other publishers followed suit. What version poured from America’s presses during those heady days? Almost exclusively the KJV. Of the more than a thousand different editions of the English Bible (or New Testament) published from 1840 to 1900, only a handful were not KJVs—and most of those were Catholic Douay-Rheims editions or editions directly from the Vulgate.

Legacy of a version

From the vantage point of the twenty-first century, it seems that the age of the KJV is finally passing in America. Of course many of the reasons the KJV was a blessing to the church also apply to the cornucopia of new translations: It is always good to have Bibles that speak to the people in a language they can both understand and relate to (see sidebar, p. 9).

But along with this benefit comes the confusion of such a multitude of tongues claiming to best speak the language of Scripture. Will any Bible translation again have the cultural and moral influence in America that the KJV once had? Perhaps because “for everything there is a season” (Ecclesiastes 3:10, KJV), a new translation will arise for this new season.

CH

By Chris R. Armstrong

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #143 in 2022]

Chris R. Armstrong is senior editor of Christian History and a program fellow at the Kern Family Foundation. He is the author of Medieval Wisdom for Modern Christians and Patron Saints for Postmoderns. This article is adapted from a longer one in issue #100.Next articles

Attackers and defenders

How “higher criticism” developed, came to America, and provoked a response

James C. UngureanuPreaching the gospel remedy

teachers, Translators, and theologians whose ideas echo into the present

Jennifer A. Boardman