Early church AD 1-500, Part 1

[pages 4–5]

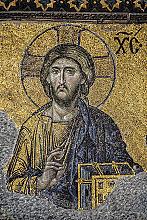

Christian imagery from the earliest centuries of the church reveals that Christ’s early followers took his teachings to heart. Neither political persecution, nor the disparity between diverse cultures, nor even the tension of doctrinal disputes could limit the spread of Christianity from its very beginning. Indeed, by 52, the apostle Thomas had already reached western India with the good news of Jesus. When he was martyred about 20 years later, the very culture that killed him would celebrate the site of his grave, adorned by a tombstone (middle, 4th c.) with a uniquely Indian rendering of the Hebrew saint. Such cross-cultural likenesses are a hallmark of Christian depictions, from the clean-shaven, Apollo-esque Good Shepherd crowning a Roman catacomb fresco (left, 3rd c.), to a 15th-c. Ethiopian illumination of Saint Mark (right), with pen and bookmaking tools in hand. The early church was missional, flexible, often underground, and prioritized above all maintaining a historical connection with Jesus.

[pages 6–7]

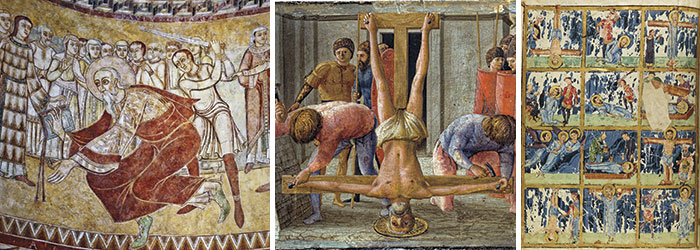

By the end of the 1st century, all of Christ’s apostles had died—most were martyred. While no early likenesses of the apostles exist, Christians would portray their deaths for the next two millennia. A medieval manuscript (right, 879–883, Byzantine) features a compilation of apostolic martyrdoms. Below (left), a Russian church’s 12th-c. fresco depicts Paul—considered an apostle because of his encounter with Christ on the road to Damascus—moments before his own beheading at the hands of the Roman emperor. Peter considered himself unworthy to die the same way that Jesus did; Masaccio’s painting of Peter’s upside-down crucifixion (middle, 1426, Pisa) includes a unique Renaissance experiment with realism in religious painting. The halo around Peter’s head is foreshortened, submitted to the physical principles of perspective. The depictions of other apostolic martyrdoms here feature halos that are wholly spiritual, slid behind saintly heads and backgrounds. Clearly, Masaccio is thinking of the halo, and perhaps Peter’s sainthood, not as intangible but as physical.

[pages 8–9]

In 70 Roman general Titus crushed the First Jewish Revolt. After seizing Jerusalem from the revolutionary government, Titus looted and burned the temple to symbolize the rebellion’s failure, ending the final period of Jewish temple worship. Eleven years later Domitian erected the Arch of Titus (left, 81, Rome) to commemorate Roman victory over this provincial coup. The interior walls, which are still standing today, feature reliefs of Titus marching victoriously home (middle left) and the desecration of the temple (middle right). It must have been shocking to 1st-c. Jews that all that remained of the liturgical instruments treasured in worship for hundreds of years—such as the golden lampstand first described to Moses for tabernacle use (Exodus 25)—were their depictions on a monument of Roman military propaganda—and that this monument was not even in Jerusalem but in pagan Rome. Writers like Justin Martyr (one of his 4th-c. manuscripts is pictured far right) saw this desecration as a sign of God’s rejection of Israel, an idea that would fuel Christian anti-Semitism for millennia. The sacking of Jerusalem forced the early church to continue extending the reach of the gospel outside of Jesus’s own homeland.

[pages 10–11]

The Alexamenos Graffito (c. 200, Rome, left) shows that Christianity endured not only waves of official persecution, but unofficial mockery as well. Discovered on a wall of the Paedagogium, where royal slaves were trained, this image of a man at the foot of a cross bearing a donkey-headed figure is captioned in ancient Greek, “Alexamenos worships god.” Scholars think it likely that this earliest-known visual rendering of a crucifixion was created to caricature the countercultural faith celebrating the ignominious death of Jesus Christ. If slaves like Alexamenos needed courage to endure the ridicule of fellow servants, thinkers like Justin Martyr needed it too. He presented his apologetic treatises defending his faith before the emperor, the Roman senate, Greek and Jewish philosophers, and Roman magistrates (can you spot these events in this 1995 icon of Justin Martyr middle left?). While thinkers like Irenaeus (middle right) also clarified doctrinal orthodoxy at this time, waves of official persecution drove churches in some cities literally underground. Even there, Christian culture flourished through catacomb paintings (right).

[pages 12–13]

The frontier town of Europos (named “Dura” in the Roman era for the hardy Roman garrison stationed there) was first settled in 300 BC and remained a major stop on both East-West trade endeavors and Persian travel. Resting on the edge of the Euphrates River in modern-day Syria, it was a cultural crossroads. By the 3rd century AD, it contained Greek temples, mystery cults, a Jewish synagogue, and one of the earliest and best-preserved house churches. With periodic waves of persecution sweeping the Roman world, house churches were central to Christian worship. Wealthy congregants hosted services within their walls and sometimes, as we see in Dura-Europos, even designated rooms exclusively for their congregations.

From the main courtyard of this house, believers filed through a large doorway (above left), then descended from one room into a low chamber (above center). Here remains the earliest known baptistry, equipped with a font big enough for full immersion. Over it is painted Christ as the Good Shepherd redeeming Adam and Eve (below center), and the adjacent walls illustrate the healing of the paralytic (below left), Jesus walking on water (below right), Mary Magdalene at Christ’s tomb, and Old Testament scenes. Invaders destroyed the city in 256, but excavations by Yale University in the 1920s (above right) uncovered a vibrant center of Christian worship employing colorful images of biblical scenes.

[pages 14–15]

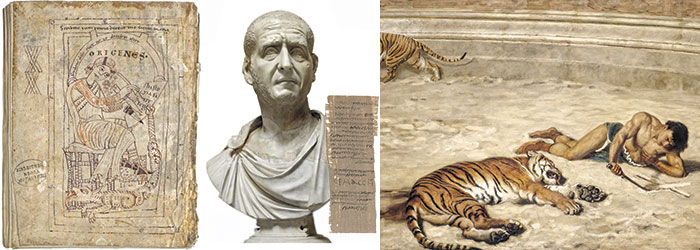

A new systematic persecution of Christians erupted in 250 under Roman emperor Decius. To the right of his bust (c. 240) is one of the documents required from individuals to enforce pagan worship: a libellus, or “little story,” submitted to the government. This one certifies that an Egyptian woman and her daughter had made the proper Roman sacrifices and is signed by three witnesses. As illustrated by the man tracing a cross into the ground in the painting A Roman Holiday by Briton Rivière (b left, 1881), the public deaths of Christians exposed the strength of the underground church even, or especially, in adversity.

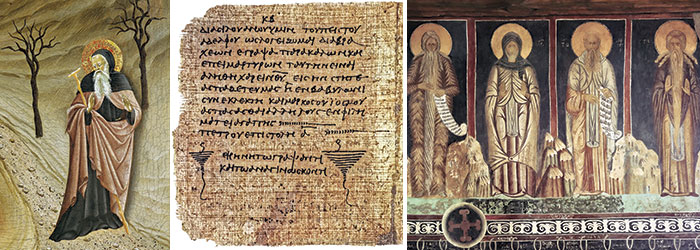

Meanwhile, Christian theologians were trailblazing new practices and cementing old ones. Some devout believers like Antony (below left) and the desert fathers (below right) began early Christian monasticism by leaving the comforts and confusion of life in the world for an exile of spiritual poverty in the wilderness. Theologians such as exegetical scholar Origen, c. 185–254, shown in a 12th-c. illumination (above left), helped to formalize the New Testament canon, using the proximity of books’ authors to Christ as the standard for inclusion. By the late 3rd century, the collection of books that believers had been reading and referencing for 150 years was already recognizable as the New Testament (below middle, late 3rd-c. manuscript of 1–2 Peter).

By Max Pointner

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #144 in 2022]

Max Pointner, issue writer and image researcher at CH, has an undergraduate degree in art history from Wheaton. He teaches history, literature, and Latin at Charis Classical Academy in Madison, Wisconsin, and directs the Charis theater program.Next articles

Christian History timeline: 2,000 years of Christian history

Events, people, and movements featured in this issue

the editors2,000 years of Christian quotations

Christians throughout the world and down the centuries testifying to their Savior

selected by the editors