Early church AD 1-500, Part 2

[pages 16–17]

In Scene of the Martyrdom of Early Christians (above), painted in 1885, Henryk Siemiradzki illustrates a Roman Empire containing great ethnic diversity.

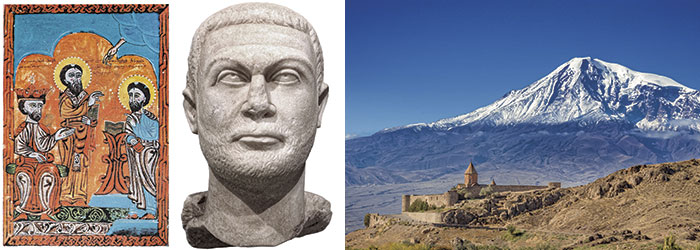

Indeed, by the late 3rd century, Rome was so large that Emperor Diocletian (middle, c. 300) sought to streamline imperial policy and simplify cultural norms. He divided his empire into four districts and recognized Christianity as such a significant counterculture that he ordered the last and most sweeping Roman persecution of Christians throughout the Mediterranean world. Diocletian stabilized Rome and even neighboring kingdoms, reestablishing Armenia between the Black and Caspian Seas under King Tiridates III in c. 287. But his staunch paganism also trickled into those realms. When Gregory the Illuminator, an Armenian refugee educated in the Cappadocian church, returned to his homeland as a royal assistant, Tiridates tortured and imprisoned him in a pit beside Mount Ararat for his attempts to share the gospel. Gregory survived there, forgotten, for 13 years while the king committed heinous acts. Rediscovered miraculously by Queen Ashkhen, Gregory returned from the pit to Tiridates; he shared with the whole royal court the news of Christ’s forgiveness (left, 16th-c. Armenian icon) and baptized the king in the Euphrates. In c. 314 Armenia became the first government to make Christianity its state religion. Today, on the slopes of Mount Ararat, the 7th-c. Nerses Chapel (right) stands over Gregory’s pit.

[pages 18–19]

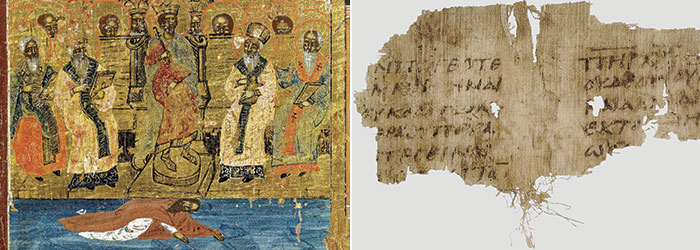

For Christians who survived the Diocletian persecution, the purge seemed to stop as quickly as it had begun. In 311 Peter Martyr, Bishop of Alexandria (left, 10th-c. Byzantine illumination), was memorably martyred by soldiers who so revered the holy man that they had to bribe one another to accomplish the deed. But the very next year, 312, Roman power struggles between the districts Diocletian had created culminated in a final battle between Constantine (center left, fragments of 4th-c. statue) and Maxentius at Milvian Bridge. Constantine’s victory immediately changed the lives of Roman Christians. As reported by the historian Eusebius, Constantine received a vision from God before the battle instructing him to paint the Greek initials of Christ (☧) on his battle flag. The emperor memorialized the Battle of Milvian Bridge on his Triumphal Arch in Rome (center right), believing he had conquered by this sign. More important, he signed the Edict of Milan in 313, legalizing Christianity. Constantine’s investment in the church did not stop there but included the funding and construction of St. Peter’s Basilica for the city’s bishop (right, 16th-c. fresco). This original cathedral would stand for over a thousand years and define the Vatican as a political and religious center. Its site remains the papal seat of the Roman Catholic Church.

[pages 20–21]

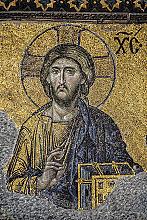

Perhaps Constantine’s most important contribution to Christianity was convening the Council of Nicaea in 325 (left, 18th-c. icon, Romania). Shortly after persecution ended, debates within the church over the nature of God the Father and God the Son began dividing believers. In 318 Arius of Alexandria claimed that while Jesus was endowed with divine power, he was not innately divine or eternal, but a special creation of God the Father. The emperor wanted to settle the issue once and for all and summoned clerical representatives to Nicaea to clarify christology. The result was the Nicene Creed (right, transcribed on a 5th-c. papyrus fragment), a clear statement of faith in Jesus as the “only son of God, God from God, eternally begotten of the Father, begotten not made.” Depictions of Nicaea, such as the one at right, often show Arius crumpled at the feet of the orthodox delegates.

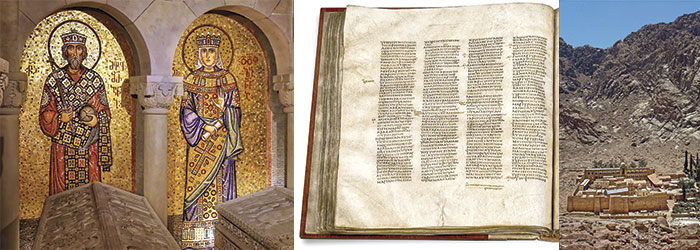

In c. 330 King Mirian III and Queen Nana of Iberia (left) became Christians through the evangelization of the missionary Nino, further establishing the Georgian Orthodox Church originally planted by Andrew. At the same time, scribes were writing the oldest surviving complete Bible, the Codex Sinaiticus (middle, mid-4th c.). Preserved in St. Catherine’s Monastery (right) next to Mount Sinai until its rediscovery in the 1700s, it contains the Old and New Testaments and the Apocrypha in Greek.

[pages 22–23]

It’s easy for Westerners to conflate early church history with late Roman history, but as we’ve seen, kingdoms outside of Rome had their own interactions with Christianity. In 333 the kingdom of Aksum (modern-day Ethiopia) adopted Christianity under King Ezana (left, mid-4th-c. coin). Athanasius (middle left, 16th-c. icon) consecrated the Aksumite bishop, Frumentius. Though the Council of Nicaea had rejected Arius’s teachings, the Arian heresy remained popular throughout the church; Athanasius, along with Ambrose (middle right, 4th-c. mosaic, Milan—probably an actual likeness of the saint!), was one of the few voices defending Christ’s divinity. In reaction to so many surrounding kingdoms adopting Christianity, Persia, which had been pushed out of Armenia by Rome in the early 4th century, began the most intense ancient persecution of Christians in 340 under Shapur II (right, 4th-c. silver plate). The purge, worse than that of Diocletian 30 years before in the West, lasted until Shapur’s death in 379, as did his hostility toward an increasingly Eastern-centered Roman Empire.

[pages 24–25]

As the Roman Empire became increasingly divided between East and West, each with its own emperor and capital city, Basil the Great of Caesarea was writing early rules for monastics. Unlike Antony’s hermetic (solitary) monasticism, Basil practiced cenobitic (communal) asceticism, inspired by the Coptic desert communes of Pakhom (Pachomius). He founded a community in Annesai around 358, near this Pontic monastery from the same period (left, modern Turkey). Basil and his brother Gregory of Nyssa (middle left, 10th-c. fresco, Turkey), sister Macrina, and friend Gregory of Nazianzus continued to fight Arianism, still theologically and politically divisive; Ulfilas, a missionary to the Goths, who translated a Gothic Bible (middle right, 5th-c. copy) in 370, was claimed by Arian and Nicene Christians alike. Byzantine emperor Valens, ruling from 364–378, subscribed to Arianism and persecuted Nicene Catholics; his successor, Theodosius I, influenced by Gregory of Nazianzus (right, 9th-c. Byzantine manuscript), pronounced Nicene Christianity the norm.

[pages 26–27]

In 380 Theodosius I made Christianity his empire’s official state religion. The next year he convened the Council of Constantinople (left, 18th-c. painting, Romania), which clarified the Nicene Creed. But Theodosius had his flaws: in 390, the emperor reacted to a provincial political murder by ordering the massacre of 7,000 civilians. Bishop Ambrose (see text and image above) demonstrated that ecclesiastical power could hold its own over the state when he excommunicated the king, demanding penance. The king repented before Ambrose wearing sackcloth and sprinkled with ashes. Ambrose also discipled Augustine, who converted from Manicheism, a gnostic cult following the platonist Mani (middle, 3rd-c. crystal seal). While Augustine chronicled his spiritual journey to Jesus in Confessions, his works after his conversion would become legendary. This Renaissance fresco (right) depicts his contemplation of the Scriptures. Not shown on this web page (see the magazine for additional images) are his baptism by Ambrose in 386, his renowned scholarship, and his shrewd evangelism.

[pages 28–29]

A 15th-c. illuminator shows Jerome (left), the patron saint of scholars, leaving behind his desert study to deepen his life in Christ. Jerome translated the Old and New Testaments into vernacular “vulgar” Latin in 405, and “The Vulgate” would be the standard Catholic Bible for over 1,000 years. Life as a hermit was brutal for Jerome, whose academic skills and mastery of an elite imperial language were of little use in the seemingly God-forsaken wilderness. Jerome battled temptation and despair, clinging to Jesus through prayer and fasting. But his exile also opened new doors for the born scholar: he studied Hebrew with a monk who had converted from Judaism, learned Greek and Syriac from travelers passing through the desert, and began to correspond with the wider world through an extensive network of letter writing. The faith of Patrick (middle, 20th-c. mosaic, Ireland) also intensified in the wilderness. He developed a heart for Ireland while enslaved there and returned to evangelize the Celts, performing a miracle on the hill of Slane in 433 to destroy heathen idols. The flourishing Celtic church nurtured a unique culture of Christian spirituality and practice. Meanwhile, the Council of Chalcedon (right) further clarified christological theology in 451—but also created the first major rift in Christianity between the Coptic Church and its northern neighbors.

[pages 30–31]

When the Council of Chalcedon affirmed the doctrine that Christ had two natures—divine and human—many northern Monophysite Christians (those who believed he only had one divine nature) decided to travel south to Africa where the Coptic Church also held this view. Arriving in Ethiopia in 494, the “Nine Saints” strengthened the church in the Aksumite Empire, establishing monastic communities and leaving behind a colorful visual culture. One of the nine, Abuna Yemata Guh, is said to have carved the remote church that shares his name out of a sandstone spire himself (left; you can see the stepped path between the two rock formations and the entrance low in the side of the taller one). Standing 8,460 feet above the valley below, it remains one of the most difficult churches to visit in the world and features a painting of the Nine Saints on its domed ceiling (right, 15th-c.).

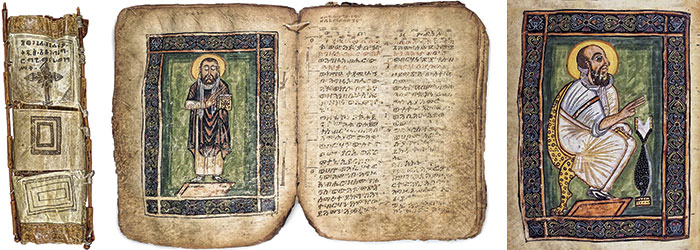

The earliest surviving complete illuminated manuscript in Christian history is also named for and attributed to one of the nine, Abba Garima. Scholars became aware of the Garima Gospels in the last century and dated them to around 500. These illuminated Gospels have likely survived in the same monastery since their creation and provide a valuable snapshot of Aksumite Christianity, language, and artistry. Shown here are Gospel writers Mark (right) and Matthew (middle), as well as the preserved original binding of one volume (left).

By Max Pointner

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #144 in 2022]

Max Pointner, issue writer and image researcher at CH, has an undergraduate degree in art history from Wheaton. He teaches history, literature, and Latin at Charis Classical Academy in Madison, Wisconsin, and directs the Charis theater program.Next articles

Christian History timeline: 2,000 years of Christian history

Events, people, and movements featured in this issue

the editors2,000 years of Christian quotations

Christians throughout the world and down the centuries testifying to their Savior

selected by the editors