Early Middle Ages 500-1000, Part 1

[pages 34–35]

Early medievals sought to connect Christian doctrine to Christian rule, believing it to be an extension of Christ’s lordship over the world and an instrument of transformation in society. An Italian mosaic from around 500 (middle) depicts Christ as a warrior: his only weapon the instrument of his death and his only shield the words of the Gospel: “I am the way, the truth, and the life.” Under his feet lie the crushed head of the devilish serpent and the submissive ravenous lion. Byzantine emperor Justinian sought to make this image a political reality. The Western Roman Empire had dissolved into several “barbarian” kingdoms, and Gothic king Theodoric ruled. While Christians there maintained Nicene doctrine under their Arian Goth overlords, some Eastern Christians had fallen into Monophysitism. Justinian reconciled the Eastern church with the pope and sent an army to retake the ancient city of Rome, unifying orthodoxy and political Christianity once again. Mosaics of Justinian and Empress Theodora (left and right) in Ravenna from 547 testify to returned Byzantine influence in Italy.

[pages 36–37]

To fund his foreign policy, Justinian imposed heavy taxes at home. In 532 a bloody riot broke out, leaving much of Constantinople in shambles. But the destruction of aging structures cleared the way for new ones, including the imperial building project that Justinian was already designing with two visionary architects. The emperor told them that price was no object and that the rebuilt Hagia Sophia, the city’s central church, should not just be huge, but revolutionary. Completed in under six years in 537, the church featured a massive central dome and mosaics, later including the 8th-c. Christ Pantocrator (left), which glistened through incense and candlelight. Today, the structure is a mosque, not a church, with the original interior long since redecorated. These illustrations by Wilhelm Salzenberg (middle and right) from 1854 attempt to recapture its Byzantine grandeur. Pagan emissaries from Kievan Rus’ in the 10th century reportedly declared, upon entering Hagia Sophia, “We knew not whether we were in heaven or on earth.”

[pages 38–39]

Outside the security and grandeur of Constantinople, the church was setting down new and deeper roots. Columba (center, 20th-c. stained glass) journeyed from his native Ireland to Scotland where he founded Iona Abbey (left) in 563. He and fellow monk Aidan founded churches throughout the British Isles and expanded missionary efforts in England. In 590 Gregory the Great, for whom Gregorian chant (which he codified) is named, was elected pope. Gregory (right, dictating to musical scribe, illumination c. 1000) both submitted to and challenged Byzantine imperialism and blazed inroads into the neighboring kingdom of the Arian Lombards. He was careful to distinguish political from ecclesiastical power and, unlike other contemporary church officials in Rome, retained an administration entirely of monks to safeguard against worldliness.

In 635 the Syrian missionary Alopen reached the court of the Tang emperor in China (right, painting c. 647). The young Chinese church produced this wall painting of Palm Sunday (right) sometime within the next hundred years.

[pages 40–41]

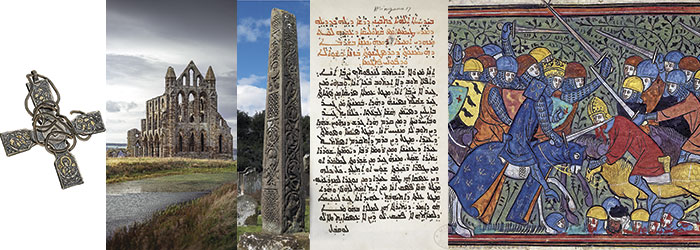

Following Columba and Aidan’s monasteries, Pope Gregory’s support of Celtic missions, and the conversions of Anglo-Saxon kings Æthelberht and Edwin in the early 7th century, the English church had both political stability and its own flavor of Christian practice. Though a synod at Whitby Abbey (center left) in 663 aligned the English church with Rome, Celtic artistic culture continued to flourish, as seen in the intricate designs of the Bewcastle Cross (center, c. 685–730) and a Scottish pectoral cross (left, 8th c.). Meanwhile, Islam, which had come into existence in 622, propelled Arab armies to challenge Byzantine Christendom in the East. African Muslims even invaded Spain. The Battle of Tours in 732 (right, 14th-c. illumination) was all that stopped Islamic influence from sweeping into western Europe. However, early relations between Christians and Muslims were not always adversarial. Around 780, Timothy I of Bagdad, patriarch of the Eastern church, cordially argued the merits of Christianity versus Islam during his two-day visit and friendly debate with Caliph Al-Mahdi (center right, 19th-c. copy of 13th-c. manuscript).

[pages 42–43]

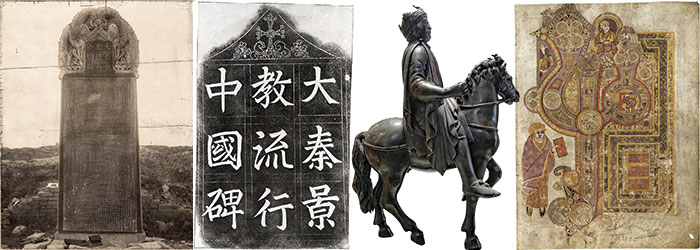

The church Alopen established in China memorialized Christianity’s influence with the Nestorian Stele (left) in 781. The monument outlines hallmarks of Christian theology: monotheism, the Trinity, the virgin birth, creation, and Jesus’s victory over death. It also emphasizes the glories of the Tang Empire, which supported the birth of Chinese Christianity, and, on the stone heading (left center), the Roman Empire, source of the “Illustrious Religion.” While the idea of Christendom was alive and well in China, it was complicated in Europe: in 800, Pope Leo I crowned Charlemagne (right center, equestrian statue c. 800) Holy Roman Emperor. This strengthened alliances between the Catholic Church and the many Western kingdoms and contested Byzantine claims to rule Christendom. Even as Charlemagne founded a new era of literacy and learning, monks in Iona Abbey were illuminating the Book of Kells (right).

By Max Pointner

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #144 in 2022]

Max Pointner, issue writer and image researcher at CH, has an undergraduate degree in art history from Wheaton. He teaches history, literature, and Latin at Charis Classical Academy in Madison, Wisconsin, and directs the Charis theater program.