High and Late Middle Ages 1000-1500, Part 2

[pages 64–65]

Both the centuries-old Nestorian Church and the more recent Franciscan missions in China were persecuted to extinction by the Hongwu emperor Zhu (left, painting on silk, 14th c.). His reign, starting in 1368, began the Ming Dynasty in China. Like Diocletian in Rome over 1,000 years before, he saw Christianity as a counterculture incompatible with the national religion, Confucianism. In Europe the 14th century marked the turn to what is called the “late” Middle Ages. Reacting against increasingly muddied motives displayed by church leadership, John Wycliffe, a brilliant English theologian, Oxford graduate, and political advisor, began writing against the institutionalism of Rome. In 1380 Wycliffe devised strategies for ministering the gospel to the common people, especially the poor—including the Wycliffe Bible, translated into the vernacular (right, 14th-c. manuscript). The pope condemned Wycliffe and the Lollards, a movement of itinerant preachers that Wycliffe inspired. As a warning not to stray from the establishment, carpenters carved images of disguised foxes and geese (center, 14th–15th-c. misericords) under many church pews in this century, representing the dangers of ignorant commoners snatched away by cunning false teachers.

[pages 66–67]

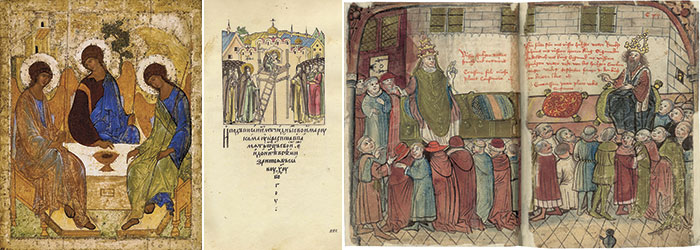

The stylized and glittering iconography of early Russian Orthodoxy gave way to looser, less glamorous icons following the Mongol invasions of the 13th century. As western Asia was consolidated under Slavic rule once again, Andrey Rublëv (center, illustration c. 1592) became the most celebrated iconographer in history. Little is known about the Muscovite monk, but he wrote the famous Trinity icon in the early 15th century (the creation of icons is known as “writing” them). The Trinity icon (left) cleverly depicts the undepictable: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit appear as the three divine messengers who visited Abraham and Sarah in Genesis 18, seated around the Eucharistic chalice. This icon, venerated by Orthodox believers for centuries, centers the three persons on the outpouring of Christ’s love for humanity. Around the same time, in 1414, Pope John XXIII and the Holy Roman Emperor (right, illustration c. 1464) summoned the Council of Constance to settle a dispute over papal succession called the Western Schism. It removed three rival popes from office (including John XXIII), elected Pope Martin V, and examined calls for church reform from figures such as John Wycliffe and Jan Hus. The council later imprisoned and burned Jerome of Prague and also burned Hus.

[pages 68–69]

After Rome fell, its eastern Byzantine counterpart remained powerful and wealthy, a bastion of culture and learning. However, by the 13th century, the Byzantine Empire was beginning to crumble. After the Mongol defeat of the Seljuk Turks, a new Islamic power, the Ottoman Turks, set its sights on Asia Minor and, by 1451, had also conquered the Balkan Peninsula. Protected for centuries by its strategic position on the tip of the Bosphorus (top right, 1455 illumination), Constantinople’s impenetrable system of walls, moats, and towers met its match in 1453: Mehmet II’s army. The brilliant Ottoman sultan commissioned a monstrous cannon 27 feet long just for his siege of Constantinople (bottom, 1535 fresco). The defenders destroyed the giant gun, but could not prevent the city’s fall. On the evening of May 28, Constantinople’s believers flocked into the Hagia Sophia to celebrate the Lord’s Supper for the last time. It was the first service Catholic and Orthodox Christians shared there in 400 years. Constantine XI, the last Byzantine emperor, attended too, committing his empire to God’s mercy. When the service ended, Constantine kept vigil on the highest walls listening to the churning siege preparations below. By the next evening, Mehmet’s artillery had shattered the walls to dust, the emperor had fought and died anonymously defending the city, and the last flame of the empire was snuffed out. Muslim Turks plastered over the Hagia Sophia’s mosaics, and the former church became at various times a mosque and a museum (top left, 20th-c. illustration).

[pages 70–71]

In the Italian Renaissance, Christian artistic practice began soaking up the humanist attention to classical Greco-Roman beauty. The Duomo in Florence (right) returned to the classically inspired Romanesque style—its massive dome completed by Brunelleschi in 1446, and its tower built a century earlier by Giotto, whose paintings were a precursor to Renaissance painting. Fra Angelico’s frescoes in the Abbey of San Marco (left, painted 1402–1455), groundbreaking experiments in texture, color, and perspective, adorned the otherwise blank walls of monastic cells as devotional prompts for faithful monks. One such monk, Girolamo Savonarola (bottom center ceramic bust, 1498, attributed to Marco della Robbia), rose to power in Florence through his sermons preached in the Duomo—attacking expressions of humanism that dipped too far into classical paganism and worldly sensuality, such as Botticelli’s Birth of Venus (1486). Convicted by Savonarola’s calls to repentance, Botticelli himself experienced deep conversion around 1490, burned many of his own edgier paintings, and turned to more devotional subjects like the Madonna and Child (top center, c. 1490). Ironically, Savonarola’s reform-minded government fell when rioters burned him in the very piazza where he had destroyed countless Renaissance works.

[pages 72–73]

Gutenberg’s invention of the movable type printing press changed the face of communication forever. His first complete book, the 42-Line Bible (left, 1554) looks surprisingly manuscript-like. It still features illuminated borders, manuscript initials heading each sentence and chapter, and rubrication (red lettering), all added by hand—notice that the red font doesn’t match the black text! The very marginal guidelines that the printing press made obsolete were likely added here for display, showing that the machine could print straighter than a scribe. During this era, in Spain King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella unleashed inquisitions upon their subjects in another late medieval attempt to solidify Catholicism. Pedro Berruguete’s painting of an apocryphal trial of Albigensian heretics overseen by Dominic (right, 1490s) actually portrays an inquisition-era auto-da-fe, or heresy trial, complete with 15th-c. costumes. Under the same monarchs, Columbus (center, engraving, 1596) became the first Westerner to establish lasting (and controversial) contact with America. The advent of Gutenberg’s technology and continued voyages to unmapped continents signaled the end of the Middle Ages in the West.

By Max Pointner

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #144 in 2022]

Max Pointner, issue writer and image researcher at CH, has an undergraduate degree in art history from Wheaton. He teaches history, literature, and Latin at Charis Classical Academy in Madison, Wisconsin, and directs the Charis theater program.Next articles

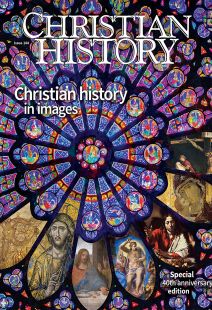

Christian history in images: recommended resources

Some resources to help you put this issue in context

the authors and editorsFavorite Christian History issues

We asked past and current team members of CH and other friends of the magazine to share their favorite issues with us and, if they wished, to tell us why.

friends and team members of Christian History magazine