Reformation to the present 1500–2000, Part 1

[pages 74–75]

By the beginning of the 16th century, much was already shifting within Christianity. In Rome Michelangelo began work on the Sistine Chapel’s ceiling (right, 1508–1512). His project was just one piece of ongoing refurbishment of the Vatican. The church also reacted to expanding exploration. In 1506 King Alfonso I, the “Apostle of Kongo” (center, 18th c.), Christianized his south-central African kingdom, personally supporting Portuguese missionaries arriving from Europe. His allegiance to Portugal politically entangled him in the growing slave trade between Europe, Africa, and the Americas. The disregard for enslaved people launched Antonio de Montesinos into action. A Dominican missionary in the Caribbean, he preached against the enslavement of the Haitians and publicly debated the issue before King Fernando. The Spanish monarch, horrified at the injustice, passed the Law of Burgos in 1512 granting rights to indigenous people and sanctioning Dominican evangelism apart from colonial operations. Montesinos was appointed the first “Protector of the Indians” in 1516, and his biblical arguments for human dignity provoked repentance from even former slave traders like Bartolomeo de las Casas, whose 1552 book The Destruction of the Indians (left) decried colonial maltreatment of the Americans.

[pages 76–77]

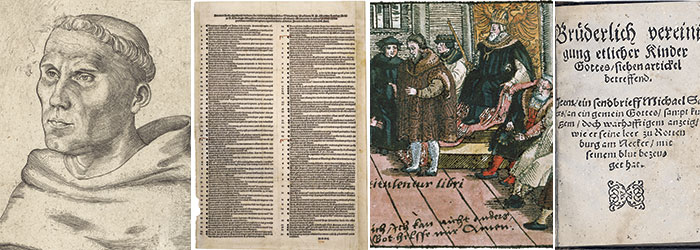

Martin Luther, depicted (left) as a young Augustinian monk by his friend Lucas Cranach, aimed for reform, not schism. Historians debate whether he actually nailed his 95 Theses to the door of Wittenberg Cathedral, but within the year they had been mass printed, like this 1517 copy (center right), and distributed throughout Europe. Luther’s critiques of Catholic practice and his emphatic restatement of the gospel launched a theological and cultural reconsideration of the established church in the West. Luther himself, though rejected officially by church and empire at the Diet of Worms (center right, 1557 woodcut), remained sacramentally aligned with Catholicism in many ways—unlike the heavily persecuted Anabaptist Radicals, who articulated their adherence to exclusive believer’s baptism, the memorial nature of the Lord’s Supper, and pacifism in the Schleitheim Confession (right, 1527).

[pages 78–79]

In 1531 Juan Diego, a Mexican Christian, told his bishop that the Virgin Mary had appeared to him and requested that he build a shrine. This reported apparition of the Virgin of Guadalupe (not shown here) became a famous icon in Latin American Christianity and a national symbol of Mexico. Around the same time in Europe, the Protestant movement wrestled with diverse theological convictions. In 1529 the Colloquy of Marburg (left, 1557 woodcut) convened to discuss the doctrine of the Lord’s Supper, over which Luther and Ulrich Zwingli differed. They agreed to disagree by writing up a list of beliefs common to both Reformed and Lutheran Christians. Much of this list was included in the Augsburg Confession, drafted by Philipp Melanchthon, which further defined Lutheran doctrine to avoid misrepresentation. A Catholic response to the Augsburg Confession, read to the Holy Roman Emperor at the 1530 Diet of Augsburg (center, engraving c. 1630), condemned 13 of its 28 articles. The Church of England, unified with Rome during Luther’s protests, severed itself from papal authority in 1534. King Henry VIII was an ostensibly religious monarch—this illumination from his psalter (right, 1530–1547) shows him singing the Psalms himself. But frustrated with Catherine of Aragon’s inability to produce an heir and infuriated by the pope’s unwillingness to annul their marriage, he signed with Parliament the Act of Supremacy (not shown here), making himself the head of the English church and thus able to divorce his wife.

[pages 80–81]

Even as John Calvin (left, woodcut 1587), a generation younger than Luther, was developing a systematic Reformed theology in Institutes of the Christian Religion, Catholicism was pursuing reform from the inside. Though sometimes termed “the counter-reformation,” the Catholic Reformation was not only a reaction to Protestantism, but also an urgent continuation of reforms that had stagnated. In 1540 Ignatius of Loyola’s Society of Jesus was approved by Pope Paul III. Committed to both strict hierarchy and cultural flexibility, the Jesuits immediately sent missionaries to the farthest reaches of the globe. Francis Xavier (1506–1552), the first of these evangelists, visited Japan (1549), and Goa, India, establishing vibrant missions in Goa (not shown), and right in Japan, folding screen c. 1600; notice the long-robed Jesuits and the puffy-trousered Westerners). The Council of Trent, meeting intermittently from 1545 to 1563, clarified Catholic doctrines and rooted out many abuses that Protestants had reacted against. Catholic reformers also employed many artists, such as Renaissance painter Titian, who some think painted the Council of Trent (center, mid-16th c.).

[pages 82–83]

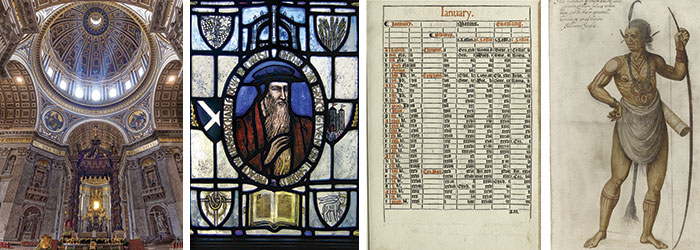

While the Catholic Reformation was seeing the construction of a new Saint Peter’s Basilica in the Vatican (left, 1560) with a dome designed by the aging Michelangelo, the new Church of England developed its own prayer book in English, in keeping with medieval predecessors for whom worshipful liturgy was an important way to experience Scripture. First compiled by Thomas Cranmer, the Book of Common Prayer would be revised over several centuries (center right, lectionary table, 1549). John Knox (center left, stained glass from his house in Edinburgh) battled to increase Reformed doctrine within the English liturgy, but when Queen Mary I realigned England with Rome, he fled to Scotland, shaping the Reformed churches there and fathering the English Puritan movement. Britain returned to Protestantism under Elizabeth I, who sent colonists to Virginia. There, in 1587, Manteo, an Algonquin (right, anonymous tribesman, c. 1590), was the first Native North American to be baptized. The first European born in North America, Virginia Dare, was christened that same day.

[pages 84–85]

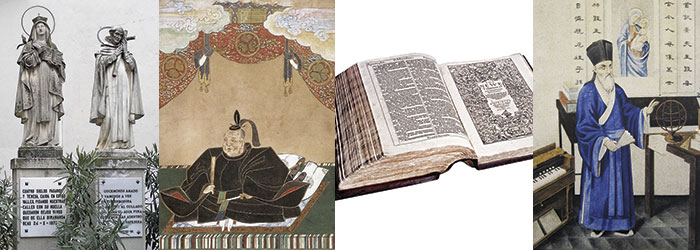

Starting in 1558 Teresa of Ávila recentered the Carmelite order around personal devotion to Jesus and pioneered contemplative prayer techniques. Teresa enlisted John of the Cross (left, with Teresa) to spark similar reform among Carmelite men, and his mysticism produced devotional classics such as Living Flame of Love, which explores the tenderness of Christ. Though Japanese shogun Tokugawa Ieyasu (center left, 17th c.) started a fierce persecution of Christians in 1606, destroying much of the fruit of the Jesuit missions, Matteo Ricci (right, c. 1600) was making fresh inroads for the gospel in China after centuries of absence. An Italian Jesuit, Ricci embedded himself in local language and culture, donning traditional scholarly attire and translating many religious and scientific works into Chinese. The now firmly Protestant Church of England produced the King James Bible in 1611 (center right). Later Oliver Cromwell won the English Civil War and revived a Presbyterian puritanism in England for a few decades. His strengthened Parliament released the Westminster Confession in 1646 (not shown), still a staple of Calvinist doctrine.

By Max Pointner

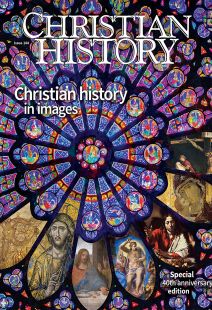

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #144 in 2022]

Max Pointner, issue writer and image researcher at CH, has an undergraduate degree in art history from Wheaton. He teaches history, literature, and Latin at Charis Classical Academy in Madison, Wisconsin, and directs the Charis theater program.Next articles

Christian history in images: recommended resources

Some resources to help you put this issue in context

the authors and editorsFavorite Christian History issues

We asked past and current team members of CH and other friends of the magazine to share their favorite issues with us and, if they wished, to tell us why.

friends and team members of Christian History magazine