High and Late Middle Ages 1000-1500, Part 1

[pages 52–53]

The High Middle Ages in Europe saw increased tensions between sacred and secular authority. As kingdoms consolidated, monarchs saw the church as a useful institution for extending their authority, while reform-minded leaders sought to purify it. Cluny Abbey, once a grassroots counterculture, was now a center of opposition to simony (the purchase of church offices). Pope Urban II consecrated it in 1095 (left, 12th-c. illumination). Described by one contemporary as the “single and only one who remains in the faith,” Countess of Tuscany Matilda of Canossa stood up to excommunicated Holy Roman Emperor Henry IV by hiding Pope Gregory VII in her castle in 1077, and she led her army against the emperor to defend the church from imperial tampering. Medieval intellectual Anselm of Canterbury (center, with Matilda, 12th-c. illumination), who himself had challenged English king William II, so revered Matilda’s intellect and spiritual example that he sent her his magnum opus, Cur Deus Homo. Under her rule Florence built Romanesque churches such as San Miniato al Monte (right, 1062–1150, Florence).

[pages 54–55]

Conversations around the Crusades today are rightly complicated. An idealistic desire to stop Seljuk violence against pilgrims to the Holy Land and check Turkish invasions of Byzantium sparked them. But many crusaders had questionable motives and perpetuated violence, even against fellow Christians. For hundreds of years after his exploits as crusader and first ruler of recaptured Palestine, Godfrey of Bouillon was the subject of many medieval romances and legends. Illustrations from “Godfrey literature” include all the major scenes of the First Crusade: Pope Urban II (top right, 14th-c. illumination) mustering hundreds of thousands of knights with his speeches in 1095; Peter the Hermit (bottom panel, 14th c.) leading the People’s Crusade on foot from France to fight the Turks in 1096; and hordes of mounted knights riding against scimitars (top left, 14th c.). European swords moved across continents and seas, some inevitably dropping into the Mediterranean (such as this shell-encrusted one, top center).

[pages 56–57]

When Bernard (left, Mallorican altarpiece, 13th c.) began a monastery in Clairvaux in 1115, the white-robed Cistercian order, founded in 1098, was a small community—sworn to the strictest rule of poverty and committed to manual labor, unusual for often comfortably wealthy monastic orders. However, Bernard’s inspiring integrity and influential counsel gathered many to the Cistercian way of life, which some historians argue contributed to growing societal wealth in the 12th century. Outside the Cistercian order, Abbot Suger, at Bernard’s urging, brought renewed religious commitment to the Abbey of Saint-Denis while sparking the most recognizable hallmark of the Western Middle Ages: Gothic architecture. Saint-Denis was in disrepair, and charge of the renovations fell to Suger. Strolling through the abbey library one evening, he pulled down a manuscript by 6th-c. Christian mystic Pseudo-Dionysius—who described all creation, from rocks to angels, as yearning for God’s holiness and saw light as an analogy of God’s incarnational sanctification of the repentant Christian. From Suger’s reading sprang the first examples of the tall, pointed arches (center in Saint-Denis, 1144) and brilliantly colored stained glass (right, in Chartres Cathedral, 1170) that so epitomize the Gothic era.

[pages 58–59]

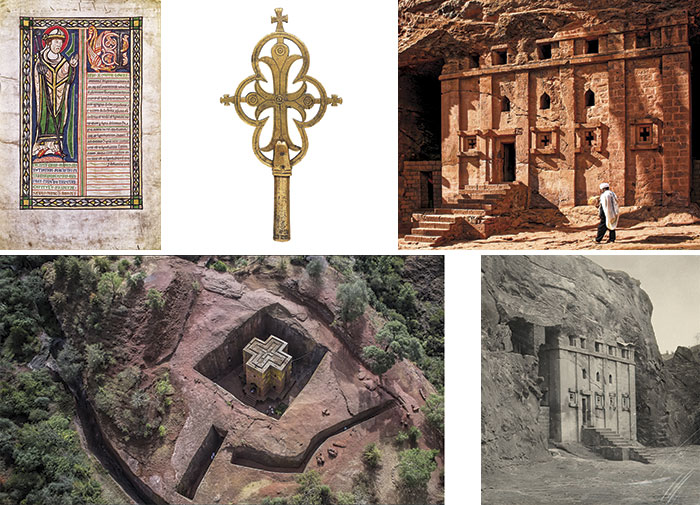

In 1150, just as Peter Lombard systematically laid out medieval theology in his book of Sentences (top left, manuscript c. 1160), a massive building project was underway in Ethiopia, where the Aksumite Empire had given way to the Zagwe dynasty. Like European Christians, African Christians had also streamed into the Holy Land on pilgrimages until Islamic conquests made the route too dangerous. Rather than pave a way back to Jerusalem through reconquest as the crusaders did, King Gebre Mesqel Lalibela, reigning in the late 12th century, sought to bring the Holy City to his kingdom. In the capital city of Roha, renamed Lalibela after himself, the king built 11 churches to symbolize the important pilgrimage sites of the Holy Land, such as Golgotha, the upper room, and the Virgin Mary’s house in Nazareth. Hewn directly from the monolithic blocks of the landscape around 1180, these churches remain wonders of the world. Most, like Biete Abba Libanos (top right in its modern state, and bottom right before a partial collapse), were carved directly into cliff sides, with interiors burrowed into the hill. Builders of the cruciform Biete Ghiorgis (bottom left) chiseled down into the hill itself to create a church accessible only by trenches through the bedrock. Lalibela remains an important pilgrimage site today as an imitation of Jerusalem. Pictured top center is a 13th-c. Ethiopian processional cross.

[pages 60–61]

Medieval cathedrals took decades to construct. Just after Oxford became an important university town as well as a political center, Christ Church Cathedral was built there between 1150 and 1180 in the Norman style, with massive pillars, wide arches, and rounded windows (right; Cardinal Wolsey added the groined ceiling in 1522). The Spanish Cathedral of Santiago de Compostella’s construction (left, baroque facade) was not simple. As the grave site of the apostle James and an important pilgrimage site from the 9th century onward, it began to feature a new Romanesque cathedral in 1075. Builders finally completed it over a century later in 1211, and later architects started to blend the original style with Gothic techniques. In the midst of these sumptuous projects throughout Europe, many churches in Italy became physically and spiritually dilapidated. It was before one of these that the young Francis of Assisi heard the words, “Go, Francis, and repair my house, which is falling into ruin.” Francis lived in evangelical poverty, radically recalling others to a life of sacrifice for others, treasuring only Christ. The pope confirmed the Franciscan Rule in 1210 (center, fresco by Giotto, 1295) and the order grew rapidly.

[pages 62–63]

Pope Innocent III (center left, 13th-c. fresco, Rome) remade the papacy into a powerful political office. He strove for reconciliation with the Eastern church, though the destruction of Constantinople at the hands of crusaders in 1204 resulted in increased tension instead. A heartbroken Innocent excommunicated his whole army. Seeking to strengthen Europe and solidify papal authority, Innocent convened the Fourth Lateran Council (left, 1250 illumination) in 1215, an ecumenical gathering he had planned for years. Innocent had confirmed the Franciscan order (Francis was unconventional, but at least he had asked for permission), but he now sought to establish theological consistency by condemning various groups as heretics and codifying Catholic doctrine on the Eucharist. He also ordered truces between warring European kingdoms in hopes of rallying support for another crusade. In 1272 Thomas Aquinas (center right, painting c. 1340) finished his towering contribution to philosophy, the Summa Theologica (right, dedication hymn from 1280 manuscript). Aquinas, drawing on Aristotle’s works newly reintroduced to the West, bridged Christian faith and Christian reason.

By Max Pointner

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #144 in 2022]

Max Pointner, issue writer and image researcher at CH, has an undergraduate degree in art history from Wheaton. He teaches history, literature, and Latin at Charis Classical Academy in Madison, Wisconsin, and directs the Charis theater program.Next articles

Christian history in images: recommended resources

Some resources to help you put this issue in context

the authors and editors