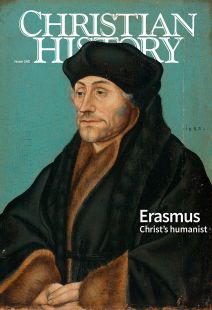

A sixteenth-century influencer

[above: H.A. van Trigt, Erasmus on his Sickbed, 1872. Jean-Pierre Vanden Branden, Erasmushuis Anderlecht, 1992—Public domain, Wikimedia]

“I commend to you the thing I hold most dear—my posthumous reputation,” Erasmus (c. 1466–1536) wrote to his friend Conrad Goclenius in 1524. He was in his late fifties and having his first premonitions of death. To assure his place in posterity, he left Goclenius 400 gold florins to publish his Collected Works. He also supplied notes for an account of his life to preface the edition. In this tightly managed story, Erasmus construed his life as he wanted it to be perceived after his death—starting by eliminating inconvenient details about his illegitimate birth.

Erasmus claimed that his father, Gerardus Helye, was pressured by family to enter the priesthood but did “what men in despair often do: he ran away,” leaving his pregnant girlfriend behind. Told that she had died, Helye did take vows, only to discover that he had been deceived. She was still alive.

The real story wasn’t so romantic. Erasmus kept silent about his older brother, and parish records suggest his father was already a priest when the older child was born. Being born to unmarried parents had serious consequences in Erasmus’s time. Laws prevented Erasmus from obtaining an academic degree or from entering an ecclesiastical office—unless he obtained a papal dispensation, which he did in 1506, with the help of friends in high places.

“No savour of Christ”

After both his parents died of the plague, Erasmus’s guardians urged the orphaned teenager to enter a monastery at Steyn near Gouda. He did so reluctantly and found the cloistered life not to his taste:

The conversations [were] so cold and inept, with no savour of Christ, the dinners so profane in their spirit, in short, the whole tenor of life was such that, if the ceremonies were removed, I cannot see what would be left that was desirable.

What bothered him most was the abbot’s contempt for secular learning. Erasmus resorted to secret study at night and in a few months “went right through the principal authors in these furtive and nocturnal sessions, to the great peril of his delicate health.” At last he got permission from the bishop of Cambrai to go to Paris, the center of theological studies, and attend lectures at the Collège de Montaigu, a hostel for poor students. The conditions were so horrid that many of the students died:

On the ground floor were cubicles with rotten plaster, near stinking latrines. No one ever lived in these without either dying or getting a terrible disease. I omit for the present the astonishingly savage floggings . . . human cruelty corrupting inexperienced and tender youth under the guise of religion.

Erasmus left within a year to make his living tutoring young men. Among them was Lord Mountjoy, who invited his teacher to accompany him to England. There Erasmus met Thomas More (1478–1535) and his circle of learned friends, who inspired him to take up biblical studies. He never graduated from a university, although the University of Turin conferred a doctorate of theology on him per saltum, that is, without the usual requirements. Not surprisingly other theologians, who had gone through rigorous examinations, refused to recognize his qualifications. “A hapless university it is for granting a degree to such a pseudo-theologian!,” sneered the Carthusian monk and theologian, Pierre Cousturier.

For the rest of his life, Erasmus worked as an independent scholar: traveling in England, France, and Italy, living in Leuven, and then settling down in Basel. He moved once more, to Catholic Freiburg, when Basel turned Protestant in 1529.

As his fame grew, admirers financed him and endowed him with sinecure ecclesiastical offices, which did not require residence. Emperor Charles V made him his councilor but rarely paid the promised stipend. Erasmus’s last will shows that he lived comfortably at the time of his death in 1536. True to his Christian principles, he disposed of his wealth charitably, establishing a fund to supply dowries for poor young women and to finance the education of deserving young men.

Back to the sources

Then and now Erasmus is considered one of the greatest humanists. What did “humanism” mean to sixteenth-century readers? The movement grew out of an admiration for the accomplishments of antiquity and a desire to emulate them. The battle cry of Renaissance humanists was Ad fontes, “back to the sources,” the writings of the ancient Greeks and Romans. The prerequisite to becoming a good humanist was an ability to read classical languages.

The movement emerged first in Italy and became popular north of the Alps at the beginning of the sixteenth century. It received a mixed reception, especially at the universities, where students deserted the traditional curriculum and flocked to humanist lecturers. Since a professor’s salary depended on the fees paid by his students, the old guard was disgruntled with these advocates of “New Learning.”

The advent of humanism also prompted unease among clergy who regarded classical studies as infected with paganism. “Virgil is burning in hell, and is a Christian to recite his poems?,” one of Erasmus’s characters exclaims in The Antibarbarians (written between 1489 and 1495). Erasmus did in fact advocate Christianizing classical learning or, as he put it, “despoiling the Egyptians” (Ex 12:36) and adapting pagan rhetoric to advance Christian ideas.

Three areas preoccupied Erasmus as a writer: language arts, education, and biblical studies (see pp. 16–19). His more than 3,000 published letters serve as a running commentary on the social, religious, and political life of his time. He provided practical instruction for aspiring writers in De copia (1512), a handbook of style; in De epistolis conscribendis (1522), a letter-writing manual; and in his collections of Parallels and Adages to be used for rhetorical embellishment. Indeed all of his works served as models of style, as handwritten marginal remarks demonstrate; sixteenth-century readers absorbed not only the content of Erasmus’s writings, but also underlined and commented on the phrases he used.

Making the classics available in print was an important humanist endeavor. Erasmus edited Latin manuscripts and produced translations of Greek texts. He translated works of physician Galen (c. 129–c. 216), satirist Lucian (c. 125–after 180), and orator Isocrates (436–338 BC), as well as the writings of Greek church fathers. He played a principal role in editing the works of Jerome (c. 342–420) and published the Greek text of the New Testament—the first printed version sold. In this process he also pioneered the principles of textual criticism, a method fully developed only in the nineteenth century.

Made not born

The subject of education figured prominently in Erasmus’s work. In On the Education of Children (1529) and The Method of Study (1511), he emphasized early instruction in Latin—and, for budding theologians, in Greek, “for almost everything worth knowing is set out in these two languages.”

Moreover he pleaded for holistic education: intellectual, moral, and physical. Innovative at the time, his ideas remain valid today. He discouraged rote learning and decried the slavish imitation of models, looking instead for “inward digestion, so that becoming part of your own system, it gives the impression not of something begged from someone else, but of something that springs from your own mental processes.”

He also emphasized the importance of a good relationship between pupil and teacher, advocating encouragement rather than the beatings commonly dealt out in his time. He noted that parents had the duty to provide for the education of their children, for “man is not born, but made man.”

Erasmus meant his instructions for boys and young men. Later, after he met the learned daughters of Thomas More, he saw the potential of women. In his time few girls received a formal education: “Scarcely any mortal man was not under the conviction that, for the female sex, education had nothing to offer in the way of either virtue or reputation. Nor was I myself in the old days completely free of this opinion.”

His change of mind is evident from two dialogues (The Abbot and the Learned Lady, 1524, and The New Mother, 1526), in which women trump men in debate and even prove, tongue-in-cheek, that women are superior to men.

Although Erasmus’s educational thought may seem progressive, the reason he gave for schooling women remained firmly rooted in sixteenth-century ideas: to make them good wives. Husbands need not fear that educated women will be less obedient, for “nothing is more intractable than ignorance.” It is better to give a woman “something to occupy her mind, or else her thoughts will turn inevitably toward evil,” he says in The Institution of Christian Matrimony (1526).

Erasmus not only wrote about children’s education, but also instructed princes and indeed all Christians. In The Education of a Christian Prince (1516), he warned the ruler not to become a tyrant. Unlike Machiavelli’s prince, Erasmus’s ideal ruler strove to be loved rather than feared by his subjects. He was peaceable and waged war only as a last resort—the kind of pacifism Erasmus embraced throughout his writings. When a dispute arose, he urged, “why not take it to arbitration?” Plenty of bishops, scholars, and magistrates might settle the matter to avoid bloodshed.

In his Handbook of the Christian Soldier (1501), Erasmus turned his attention to the education of all Christians. They must progress from “visible to invisible things,” from the outward observance of rites to inner piety. He termed these principles the “philosophy of Christ,” based on the words of Christ in the Gospels.

A mere grammarian

As long as Erasmus wrote on education and dispensed moral and spiritual advice, he met with widespread approval. Once he applied his language skills to biblical texts, however, academic theologians reacted with alarm to the incursion onto their turf of an unqualified layman, a mere “grammarian.” Tensions first arose when Erasmus lampooned theologians in his most popular work, Praise of Folly (1511), a satire on human foibles. The quibbles of the theologians were so tortuous, he wrote, that “the apostles themselves would need the help of another Holy Spirit” to understand them.

Grumbling arose about Erasmus’s insolence, but theologians took action against him only after he published his magnum opus, his New Testament (1516). It contained the Greek text, based on manuscript evidence, together with a corrected and improved version of the Latin Vulgate. It gave the theologians fodder for complaints, not only because of the changes but because Erasmus offered a wealth of annotations explaining his corrections. The popular work went through four editions during Erasmus’s lifetime. In subsequent years he also wrote Paraphrases (paraphrasing the New Testament books) as well as commentaries on selected psalms.

In explaining the psalms, Erasmus followed Latin and Greek exegetes since he had never pursued Hebrew studies. In this matter as in other contexts, he showed the anti-Semitic bias characteristic of his time. Concerned that the study of Hebrew might revive Judaism, he argued, “there is no pestilence more adverse and hostile to the doctrine of Christ.”

He questioned the value of Hebrew commentaries: “I see that that race is full of the most inane fables and succeeds only bringing forth a kind of fog . . . I would rather have Christ tainted by [the scholastic] Scotus than by that nonsense.” By contrast he saw Muslims as “half-Christians,” presumably because Islam recognizes Christ as a prophet.

At the time of his writing, the Turks posed an immediate threat to the West, besieging Vienna in 1529, but while Luther already promoted war against them, Erasmus continued to preach pacifism in his commentary on Psalm 28 (1530). He also discouraged strife among Christians in his exegesis of Psalm 83 in 1533, commenting on the disturbances caused by religious wars. He urged that discussions be carried on soberly and “in the spirit of accommodation,” calling for a church council to settle unresolved doctrinal issues.

Erasmus was often regarded as a partisan of the Reformation. To Catholic theologians Erasmus sounded too much like Luther. As a result the theological faculty of Paris condemned his works in his own time, and the church placed them on the Index of Prohibited Books after his death.

In his New Testament annotations, he questioned the status of sacramental marriage and confession, examined the “real presence” in the Eucharist, and challenged the scriptural basis of masses for the dead and the adoration of saints. To some he seemed to subscribe to Luther’s principles of sola fide, sola scriptura, and sola gratia, as well as to his idea of Christian freedom. The phrase “Erasmus laid the egg, and Luther hatched it” became proverbial (see inside front cover).

The spirit is no skeptic

Erasmus agreed with Luther’s criticism of superstitious practices and church abuses, but never advocated doctrinal changes. On the contrary he deplored Luther’s aggressive tone and disparaged all sectarianism. To prove he was no Lutheran, he debated the reformer over the question of free will.

In his Diatribe or Comparison on Free Will (1524), he offered proof that the scriptural evidence is ambivalent. He therefore suspended judgment, explaining he would “seek refuge in skepticism” and fall back on consensus and the traditions of the church. In his sharply worded reply, The Bondage of the Will (1525), Luther insisted on the clarity of Scripture and quipped: “The Holy Spirit is no skeptic.”

Erasmus also feared that humanism would become entangled and submerged in the Reformation debate. His enemies had long resented the New Learning, he wrote, and Luther’s books gave them a handle “to tie up [the Reformation] with the study of the ancient tongues and the humanities.” Although Erasmus could not prevent the conflation and confusion of the two movements, humanism survived, and so did Erasmus’s reputation as its standard-bearer.

Even the Catholic apologist Johann Eck (1486–1543) had to admit that “Erasmian” stood for “all-round learning and copious powers of expression”; according to the Swiss chronicler Johann Kessler (1502–1574), it meant “whatever is skilled, polished, learned, and wise.” Erasmus’s ideas saw a revival in the eighteenth century. German philosopher and sociologist Wilhelm Dilthey (1833–1911) even called him a forerunner of the Enlightenment—“the Voltaire of the sixteenth century” and “founder of religious rationalism.”

What can Erasmus give readers today? He remains an aspirational figure, even if Latin is no longer the common scholarly language and he no longer serves as a model of eloquence and style. His ideas have remained alive, if in some cases abstracted from their original context. The Erasmus University in Rotterdam declares that the man who gave the institution its name stands for “global citizenship, social commitment and an open and critical mind.” No doubt Erasmus remains an influencer, as he was in his own time. CH

By Erika Rummel

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #145 in 2022]

Erika Rummel is the author of over a dozen nonfiction books, six of them on Erasmus, and several novels, and is the editor of the Erasmus Reader. She is professor emerita of history at Wilfrid Laurier University and is an editor and translator for the Collected Works of Erasmus.