“Mighty acts”

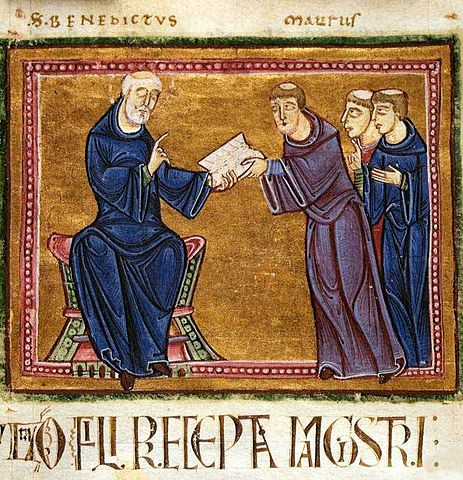

[St. Benedict delivering his Rule to St. Maurus and other monks of his order. France, Monastery of St. Gilles, Nimes, 1129—public domain, Wikimedia File:St. Benedict delivering his rule to the monks of his order.jpg]

The Holy Scripture and every age of the church report countless instances of dramatic encounters with God. . . . The initial response to God’s presence almost always involves repentance. This is often followed by a sense of happiness or joy. Frequently the people involved report some kind of interruption of bearings, such as losing track of time. The encounters are often disorienting. For instance, when Isaiah encountered God, he fell to the ground and exclaimed, “Woe is me” (Isa. 6:5). Likewise, when the disciples experienced the divine light on the Mount of Transfiguration, they immediately fell to ground, terrified (Matt. 17:6). Equally common is an emphasis on the suddenness or unpredictability of the encounter. In the book of Acts, the disciples were gathered in a room for prayer when “suddenly, there was the sound of a mighty rushing wind” (Acts 2:2). . . .

Some people who identify as Christians are functionally cessationist when it comes to the manifest presence and power of God. They admit that God may have been discernibly present in the Bible, which is to say, during the age of God’s “mighty acts” in history, but they doubt that God is present in similar ways today. . . .

[For other believers], nothing about the basic concept of outpourings or revivals is incompatible with either Holy Scripture or classical Christian doctrine and theology. At the heart of the concept of outpourings is the idea that, from time to time and in ways that are unscripted and beyond human control, God makes God’s presence and power manifest in a manner that is readily discernible, that leads to repentance and deep joy, and that conveys life-changing forgiveness and grace. . . .

Revival and everyday prayer

If we are seeking to welcome revivals, but not manufacture them, how should we think and live? First we should appreciate and celebrate the presence and action of God in the “ordinary” means of grace. Stretching all the way back into the priestly tradition in the Old Testament, God works through prescribed rituals and activities. God often, indeed usually, works through means that he has ordained and established.

God works steadily and regularly through the sacraments of the church. God is active in . . . patterns of mentoring, discipleship, and accountability. God is present and active in personal Bible study and prayer, and God meets with his people wherever “two or three are gathered” in Christ’s name (Matt. 18:20). God is working in the lives of God’s people in the ordinary rhythms of life . . . to form Christ-like attitudes in hearts and minds and affections as practices and habits form godly character and as virtues are planted and nurtured. . . .

Second we should understand and appreciate—and indeed receive and celebrate—the extraordinary activity of God. Just as it is true that God most often works in ordinary ways, so also it is true that God sometimes works in extraordinary events. Stretching all the way back into the prophetic traditions of the Old Testament, God sometimes works in unscripted and unanticipated ways. When God does this, the result is often not only unexpected but indeed surprising and sometimes even disruptive. . . .

Beginning in the Old Testament, moving through the New Testament, and at various points in the history of the Christian church around the world, we see that divine action is not—and cannot be—limited to what we have come to expect. What should our response be when we are surprised by such events (and it is important to keep in mind that they are, by their very nature, surprising)? Should it not be like the response of Mary to the ultimate surprising work of the Holy Spirit? Should we not, like her, say “let it be with me according to your word” (Luke 1:38)?

By Jason E. Vickers and Thomas H. McCall

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #149 in 2023]

Adapted from Outpouring by Jason E. Vickers and Thomas H. McCall. Reprinted with permission. Jason E. Vickers is professor of Christian theology and William J. Abraham Chair of Wesleyan Studies at Truett Seminary. Thomas H. McCall is Timothy C. and Julie M. Tennent Professor of Theology at Asbury Theological Seminary.Next articles

Countering insult and shame

Pope Gregory VII and the Cistercians tried to reform the church from both above and below

Greg PetersBernard of Clairvaux’s labor of love

Mentor to popes, advisor to royals, arbiter of heresies, and author for the ages

Paul RoremLooking for the last emperor

Some medieval thinkers and writers sought reform because they thought the end was coming

Randolph DanielPoor in spirit, new in Christ

While they looked for renewal, the Waldensians looked like trouble

Alan Kreider