Winds of spiritual renewal

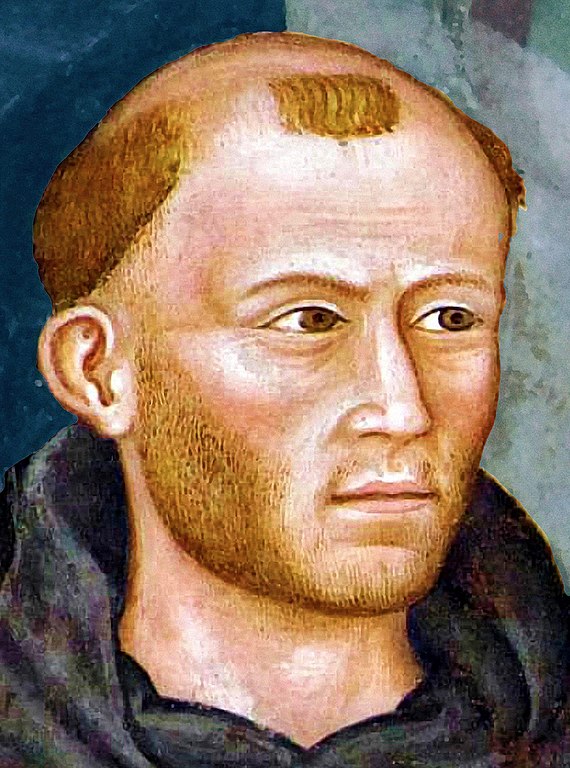

[Andrea di Bonaiuto, Meister Eckhart in Via Veritas, Church Triumphant, fresco, 1365 to 1367, Spanish chapelle, Santa Maria Novella, Florence—[CC BY 3.0] Wikimedia File:Meister Eckhart base copie.jpg]

Fourteenth- and fifteenth-century Europe witnessed arguably the most extensive spiritual renewal of the laity since the early church. Termed the “harvest of medieval mysticism” by Bernard McGinn, these two centuries saw revival in England, Italy, and other regions of Europe, but especially in the German territories known as the Holy Roman Empire and in the Lowlands.

Spiritual renewal is marked by personal faith. Before the High Middle Ages, the average layperson certainly attended church and assented to teachings of the faith; however, with the liturgy and Bible both in Latin, few would have been able to appropriate their faith on a truly personal level. In addition many priests and bishops seldom gave sermons, and Bibles and devotional books were few and prohibitively expensive.

But with the translation of the Bible into vernacular languages (Middle German, French, Dutch, Italian, English) beginning in the twelfth century, everything began to change. More laypeople were learning to read and write in the vernacular, and now portions of the Bible were available to them. Many became hungry for deeper Christian lives. Devotion of the time stressed the experience of God’s presence when taking the Eucharist, as well as individual prayer, during which believers could encounter the consolation of Christ’s presence.

Three Preachers light a fire

In the fourteenth century, three key figures of the Order of Preachers (Dominicans) sought to meet the growing spiritual hunger and lit renewal fires in the Rhineland: Meister Eckhart, Henry Suso, and Johannes Tauler. Traveling and preaching extensively, they laid the spiritual foundation for this renewal. In addition many of their sermons and books were distributed in German.

Eckhart (c. 1260–c. 1329), a brilliant scholar and speculative theologian, served twice as the Dominican magister at the University of Paris, as well as being the Dominican provincial of Saxony for a time. In his preaching and writing, Eckhart emphasized all things flowing from God and all things returning back to God through Christ. For us to return to God, he posited, we need radical detachment from all that we cling to. Then we have Christ born in us each day and experience Gelassenheit, “yielded-ness,” as we savor inner peace that comes from surrender to God.

Building on Eckhart’s thought, Henry Suso (c. 1299–1366) taught the need for both contemplation and action in the true Christian’s life. Although early in his life Suso had engaged in severe self-mortification, he turned away from such ascetic practices. He highlighted the experience of jubilus, uncontrollable joy and jubilation as we move toward spiritual maturity and union with Christ.

Suso became one of the most influential spiritual writers of the Middle Ages, especially through his book, the Clock of Wisdom (c. 1329–1330), which was second only to Thomas à Kempis’s Imitatio Christi (Imitation of Christ) in its circulation at the end of the Middle Ages.

Johannes Tauler (c. 1300–1361) likewise traveled and preached widely to laypeople, households of Beguines, and convents of Dominican nuns as he emphasized becoming a “friend of God.” Influenced in part by Eckhart, Tauler’s sermons were very practical and down-to-earth, calling people to obey Scripture, walk in humility, and embrace challenging circumstances in their lives, since these ultimately come from God. He emphasized the nobility of the human soul that is created in God’s image.

Tauler also preached that for us to grow spiritually, we must regularly die to ourselves. In particular Tauler saw two great seasons of trial, darkness, and dying along the path toward maturity. The first of these occurs in the early years of Christian growth when we die to the fleshly desires of the “old self” (Col. 3). After such purgation we enter a victorious season of the Christian life during which we walk in triumph over temptation, serve God tirelessly, and love God so much we would willingly die as martyrs for our faith. Here we experience jubilus, spiritual elation in which we “sometimes are shouting, sometimes laughing or singing.”

Such an ecstatic period, however, is followed by an even harder season of darkness that can endure for years. During this dark time, we must relinquish the ways in which we previously experienced God’s presence and our limited mental images of God. Those who pass through such darkness, however, emerge on the other side into spiritual maturity and the blessedness of bridal union with Christ. Interestingly John of the Cross later followed the same progression in his “dark night of the senses” and “dark night of the spirit,” possibly influenced by Tauler.

Becoming Friends with God

Suso and Tauler, along with the priest Henry of Nördlingen (whose dates are unknown), became leaders in a renewal movement in the Rhineland known at the Gottes frúnde—Middle High German for “Friends of God”—with centers in Basel, Strasbourg, and Cologne.

The Friends of God were an unstructured association of Christians seeking a deeper life of faith, comprised of a remarkable cross section of late-medieval society, including laywomen and laymen, Beguines, priests, and Dominican nuns and friars, who shared friendships and maintained correspondence with each other. (Read more about Beguines in CH issue #127.) Such inclusion of laypeople marked a significant shift in the church during the late Middle Ages.

A key layman of the Gottes frúnde, Rulman Merswin was a wealthy banker and a friend of Tauler’s. He and his wife, Gertrude, rose to leadership in the movement around Strasbourg. As well as writing a number of books on spiritual growth, Merswin purchased an unused convent on an island in the Ill River, naming it Green Island. He and his wife established it as a center for retreat and contemplation, but it never became an enduring spiritual renewal center.

Three additional key spiritual writings emerged in the milieus of the renewal along the Rhine. The most significant of these, the anonymous work Theologia Deutsch (or Theologia Germanica), offers a rich theology of spiritual growth. Martin Luther bestowed this title on the book when he published it in 1516 and again in 1518. Because many of its themes are the same as those of Johannes Tauler, Luther speculated in his first edition that Tauler might have been its author, though most likely a knight of the Teutonic Order in Frankfort wrote it.

The Theologia Deutsch follows the metaphysics and spirituality of the sixth-century spiritual author Pseudo-Dionysius. It teaches that to come to know the Creator who is Being himself, true Christians must become detached, not only from material things, but from “I,” “me,” “self,” and “mine.” That detachment comes by way of submitting to all “creatures”—that is, our creaturely circumstances and situations of life—which often entails hardship and cultivates humility and poorness of spirit.

Becoming poor in spirit comprises the first major step of Christian growth—purification—which is followed by two other stages: illumination and union. In the ultimate stage of spiritual union with God, mature souls love only God who is the “one true and perfect Good.” In doing so they truly “become partakers of the divine nature” (1 Pet. 1:4). Yet as long as believers are in their earthly bodies, warns the Theologia Deutsch, they must beware of sin and self-will, not thinking themselves beyond temptation.

A second anonymous work, The Book of Spiritual Poverty, likewise highlights the need for detachment from material possessions and from self-will. Because it presents much of the same message as did Tauler, it is also thought to be Tauler’s writing. The third significant work, The Life of Christ by Ludolf of Saxony (d. 1378), shows readers how to meditate on Scripture by envisioning Jesus’s ministry and Passion, a devotional method especially helpful in personalizing God’s Word. In coming years Ludolf’s book would greatly impact the Devotio Moderna and John of the Cross.

Stoking renewal in the lowlands

Some 120 miles west of Cologne, Jan van Ruusbroec (c. 1293 –1381) was concurrently stoking the fires of renewal in the Lowlands, first through his preaching at the Cathedral of St. Gudula in Brussels and then through his writing, mostly done while he lived in Groenendael.

Ruusbroec emphasized the necessity of practicing virtues in the spiritual life. Those who move from the outer spiritual life to the inner spiritual life experienced jubilus—that uncontainable joy of God’s presence and consolation. Ruusbroec, like Tauler, described the painful darkness we experience following this season when we no longer enjoy frequent spiritual consolation. Such a time, however, is necessary to liberate us from clinging to emotional experiences, and it frees us to love God simply as God.

That freedom leads us into mystical union with God, the deepest oneness we can know before heaven. Given their close geographical proximity, it is quite possible that Tauler and Ruusbroec influenced each other’s thought. Ruusbroec’s best-known work, Spiritual Espousals (1350), is recognized as a great masterpiece of Christian spirituality.

On fire for God

Ruusbroec influenced a key preacher in the Lowlands, Geert de Groote (c. 1340–1384), founder of the Devotio Moderna, meaning “devotion, or spiritual renewal, in our time.” A significant revival movement centered in the Lowlands and northern German territories, the Devotio Moderna began just before de Groote’s death and flourished through the fifteenth century. The movement included laity as well as those who took permanent religious vows.

Laywomen known as the “Sisters of the Common Life” formed the first branch of the Devotio Moderna, living in households where they practiced devotion and sought to live out their faith, sharing everything in common. Their first household was in de Groote’s own home, and in time they grew to nearly a hundred houses, accommodating several thousand laywomen. In lesser numbers lay “Brothers of the Common Life” formed households as well, engaging in copying Bibles and works on spiritual growth, then printing them after the printing press became available in 1454.

Both men and women were expected to read the Bible daily since Bibles were ever more accessible. Spiritual emphases included love, humility, obedience, purity of heart, and being aflame for God. The brothers began orphanages and schools for boys who could not afford an education. They sought to shape the boys’ character while also teaching them to read so they could study the Bible. Erasmus of Rotterdam and Martin Luther both received part of their education from the brothers, and both further promoted public education and reached even more laity across Europe with Scripture and an emphasis on personal faith.

The other main branch of the Devotio Moderna was the “Windesheim Congregation of Canons Regular,” a network of women’s and men’s houses. As canons and canonesses, they took permanent religious vows and followed Augustine’s Rule. Over time some of the households of the Sisters and the Brothers of the Common Life adopted Augustine’s Rule and joined the Windesheim convents, giving more structure to their corporate devotion as well as placing them under the jurisdiction of the church rather than the local city council.

The largest branch of the movement, the Windesheim Congregation, likewise published Bibles and devotional works. In fact the Devotio Moderna produced 75 percent of Bibles and devotional books published in the last decades of the fifteenth century. The most famous member of the canons was Thomas à Kempis, whose practical guide to the spiritual life, Imitatio Christi (c. 1418–1427), is said to be the most published book of all time next to the Bible.

Forerunners or standalones?

This widespread spiritual renewal in the late Middle Ages raises a question for contemporary Christians. Were these revivals forerunners of Luther and the reformers, as Protestant scholars argue? Or should they be interpreted—and appreciated—as genuine renewal movements in their own right that brought men and women into a deeper faith as they remained in the Catholic Church?

On the one hand, the spreading fires of revival did prepare the way for Protestantism. Emphases on Scripture, lay spirituality, widely circulated devotional writings (especially in vernacular languages), cross-pollination between laity and religious, and ever more widespread public education—along with sharp criticism of abuses in the church’s hierarchy: the Protestant Reformation built upon and further developed all these themes. Both Erasmus and Luther, educated in the schools of the Brothers of the Common Life, could follow where the thread began.

Yet, just as Erasmus “laid the egg that Luther hatched” (see CH #145) but refused to join the Protestants because he did not want to see the body of Christ divided, so did these groups avoid the path of schism, a path that various other movements across Europe took in the Middle Ages. Fully conscious of problems in the Roman Catholic leadership, these fervent believers experienced profound revival in their faith and sought to live out their love of God and neighbor in their given contexts. Indeed the Brothers of the Common Life who lived into the sixteenth century never felt a need to join with the Protestants, and Luther never closed down their buildings as he did those of the monks and nuns.

On whichever side of this debate we might stand, a growing number of Christians today—both Protestant and Catholic—value the need for movements of spiritual renewal in the universal body of Christ. They share hymns and worship music, pray together, and stand against today’s culture of death. They appreciate the common heritage we share and recognize that from the beginning the church has been semper reformanda, always reforming, as we “become mature, attaining to the whole measure of the fullness of Christ.”

Throughout the history of Christianity, fresh winds of spiritual renewal have blown again and again, bringing new life to the church and drawing believers into a dynamic personal faith. While some of these renewals are well-known in our day, many others are less famed yet no less important.

To get a fresh glimpse of such revival movements opens our eyes to a broader view of the Body of Christ beyond the circle of our own Christian experience. Such a perspective also invites us to open ourselves afresh to the blowing of God’s Spirit. Above all seeing God’s work in the past expands the horizons of our faith to appreciate a God who is ever-faithful, ever-active, and ever-welcoming us to draw closer to him in love. CH

By Glenn E. Myers

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #149 in 2023]

Glenn E. Myers is professor of church history and theological studies at Crown College and the author of Seeking Spiritual Intimacy: Journeying Deeper with Medieval Women of Faith.Next articles

First, preach Christ’s gospel

Many medieval preachers intended their sermons to renew and revive

Beth Allison BarrDormant and exploding volcanos

Revivals kept breaking out in the Reformation—but sometimes when people didn’t want them to

Edwin Woodruff TaitWhat does it mean to live in Christ?

Reforming and challenging words from Martin Luther

Martin Luther and translators