Senior editor’s note

How do you tell the story of Christian history? And what makes Christian History Christian history?

The first time I ever had to think about those questions from an editorial standpoint was in 2012, when I wrote my very first editor’s letter for CH, introducing our issue #104 on Christians in the Industrial Revolution. I went back and reread that letter before I wrote this one, and it proceeded much the same way I often have proceeded in these letters: a summary of the articles in the issue coupled with some thoughts about how all of this applies to us today. I concluded:

The articles here are intentionally varied; we may not agree with, or endorse, all those who brought the resources of the Christian faith to bear on economic change. But this range of articles shows how many, many people tried to apply Jesus’s teachings to the world they lived in, during strange and confusing times.

Obviously, these stories are also relevant to our own day. We also live in a time of tremendous economic and technological dislocation. We also wonder which way to turn. Let the voices in this issue help remind us that Jesus is Lord; the same yesterday, today, and forever.

In so concluding, I was stepping (faithfully, I hope) into a mission that was already long at work.

Since the very beginning of Christian History in 1982, the magazine has tried to do something that—though we hope it looks easy on the page—is very, very hard. It’s very easy to tell the story of Christianity from “outside”: through purely naturalistic eyes, as something caused and acted out by humans sociologically, economically, and culturally. (Trust me on this: I survived getting a PhD at a secular university.) It’s also very easy to tell the story of Christianity from “inside”: as a story of triumph, conversion, and purity, with clear heroes and villains and with no one ever being allowed to have mixed motives. (The technical word for this kind of history is “hagiography,” and you can trust me on this too, because over the past 11 years I’ve read a fair amount of mail from people who want hagiography.)

Making Christian history

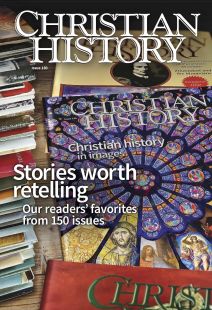

But what Ken Curtis set before us as a mission, and what we’ve tried to do for 41 years and—as of this issue in your hands—150 issues, is neither of those things. We have tried to tell a story that is “intentionally varied”; that takes into account social, cultural, and economic forces; that recognizes mixed motives and disagreements; that acknowledges the dead ends and detours the people of God have sometimes been led to; that criticizes where criticism is necessary and challenges the myths we may have cherished—all while affirming that God is still in control.

Can we point to any single historical act and say that we absolutely know the will of God on the matter? I would say that the answer is almost always “no.” Can we point to the history of the church as a whole and say that we perceive the Holy Spirit at work, even at times when it seems an absolute mystery as to how and where? I would say that the answer is always “yes.” As you read the articles in this issue, drawn from the most popular and most important we’ve published in the previous 149 issues, let the voices in this issue help remind us that Jesus is Lord; the same yesterday, today, and forever.

And that is what makes Christian history. And also Christian History. CH

By Jennifer Woodruff Tait

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #150 in 2024]

Jennifer Woodruff Tait is senior editor of Christian History magazineNext articles

Managing editor’s note

The vision that Ken had from the very beginning lives on at Christian History Institute's core.

Kaylena RadcliffThe history of Christian History

What made CH what it is today? Our unique beginnings guide our mission

Chris A. Armstrong and Bill Curtis